Four Takeaways from Treasury Secretary Yellen’s Trip to Africa

The visit launches a year of high-level U.S. engagement with Africa to build a relationship of ‘mutual cooperation and greater ambition.’

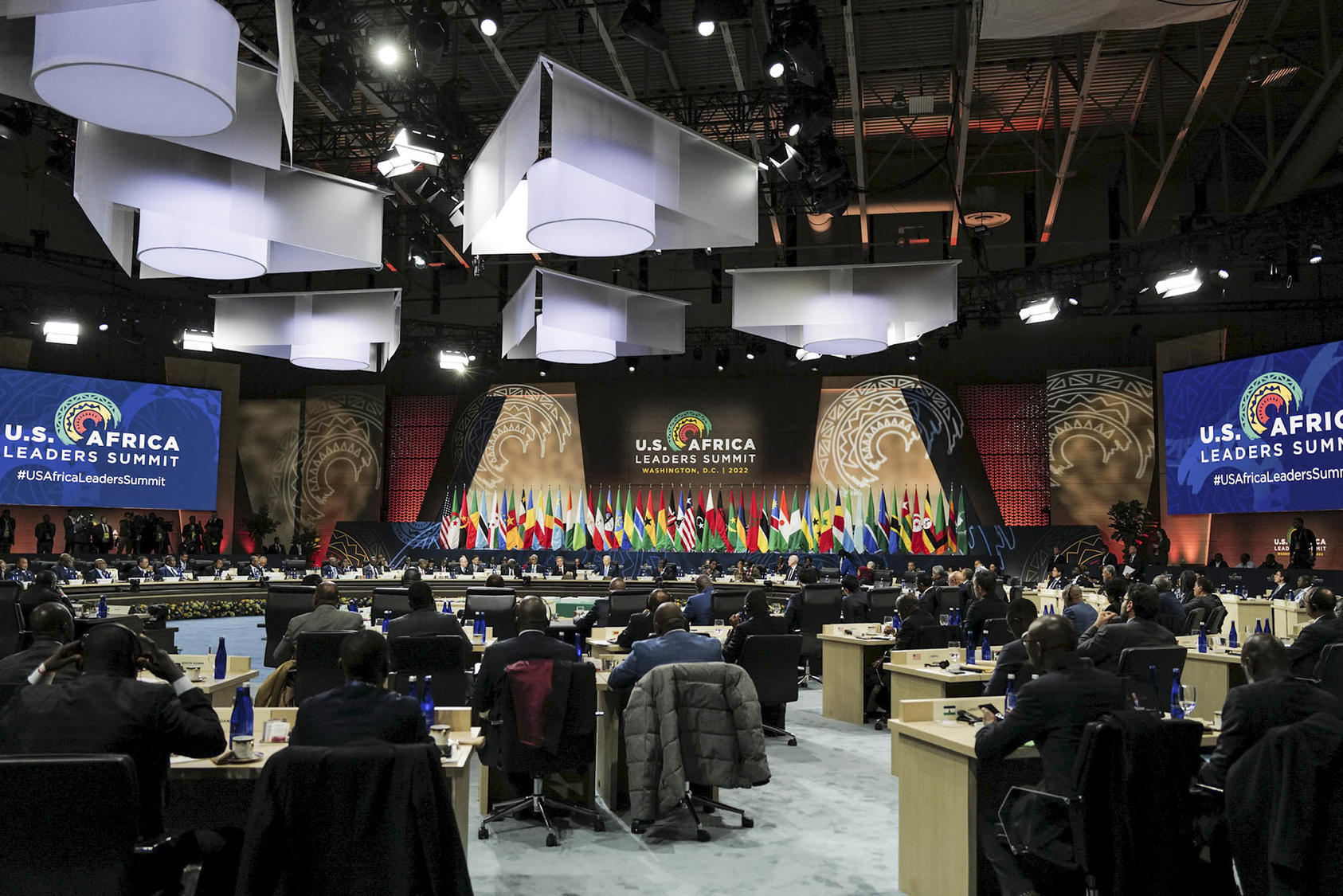

Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen’s recent 10-day trip to Africa kicks off a year of sustained, high-level U.S. engagement, aimed at demonstrating that the Biden administration is “all in on Africa, and all in with Africa” following December’s U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit. With trips from the president, vice president, and other cabinet secretaries in the works, this “super-charged” U.S. diplomacy is moving beyond the typical secretary of state visits. A close look at some of the issues encountered by Yellen on her trip demonstrates that showing up on the continent may be the easy part of going all in with Africa.

Here are four takeaways from Yellen’s trip to Senegal, Zambia and South Africa.

1. The United States recognizes that “Africa will shape the future of the global economy” and is ready to boost its partnerships across the continent.

Yellen began her trip in Senegal by noting “Africa will shape the trajectory of the world economy over the next century,” pointing to the benefits of a rising educated, urbanized and more digitally connected population. Indeed, in the next dozen years, the number of working-age Africans will be greater than that of the rest of the world combined. More workers can drive growth and create wealth, a growing middle class and a larger market for U.S. goods and investment opportunities.

But as the secretary rightly warned, Africa’s youth explosion could go in the opposite direction: “Throughout history, young populations without opportunity can spell greater risk of unrest and conflict.” She described the need to provide inclusive economic opportunity for the next generation of Africans as the continent’s “most daunting and most promising task.”

While African economies have made great strides over the last two decades, the need for fundamental foundations such as quality infrastructure, reliable power and transparent business practices continues. Indeed, Africa’s only representative in the G-20, South Africa, has trouble simply keeping the lights on.

The United States has stepped up its rhetoric behind supporting “game-changing” infrastructure projects in the developing world through the G-7’s five year, $600 billion Partnership for Global Infrastructure. For such projects to succeed, they cannot simply be dictated by government officials alone but must be closely linked to the needs of the private sector.

For its part, the United States would do well to step up its focus on bolstering Africa’s digital infrastructure. This would help connect African economies, play to the United States’ comparative advantage and speak to the young African tech entrepreneurs that are changing the face of African economies. At the recent Africa summit, President Biden announced a new $350 million digital initiative to expand internet access and provide Africans with increased digital skills.

Overall, in the last two years, Yellen said Washington has helped facilitate more than 800 trade deals across the continent and is “strongly supportive” of the African Continental Free Trade Area that will encompass 1.3 billion people.

2. Zambia’s debt crisis has far-reaching implications — and China is a “barrier” to resolving it.

In Zambia, Yellen rightly called out Beijing for being a “barrier” to ending the major copper producer’s debt crisis and noted that it had “taken far too long already to resolve.”

In 2020, Zambia defaulted on about $17 billion of debt, leaving its economy severely weakened and in need of “desperate debt relief.” More than a third of this debt is owed to Chinese lenders. To help get out of the red, Zambia has worked with the International Monetary Fund to secure a $1.3 billion bailout package. But Lusaka won’t be able to access this relief until its underlying debt is restructured. The prolonged stand-off threatens to put more into poverty and joblessness with an inability to access loans to build for the future.

Years ago, such restructurings would be handled through the Paris Club of wealthy, mostly Western nations. But over the past two decades the lending landscape has changed, with China especially — as well as the private sector — rapidly accelerating overseas lending with little transparency.

U.S. estimates of Chinese lending range from $350 billion to a trillion dollars. This type of opaque lending “can leave countries with a legacy of debt, diverted resources, and environmental destruction,” Yellen warned Africans as she began her trip.

As the pandemic exposed significant debt vulnerabilities of developing countries, the international community increasingly realized that a new structure must be put in place to account for the shifting lending landscape. In the fall of 2020, G-20 countries — including China — announced the establishment of a Common Framework for Debt Treatments to provide relief to indebted countries, buttressed by credible policy reforms to help them stabilize and grow their economies. Such “fair burden sharing” among all creditors is essential to ensuring one lending country isn’t benefiting at the expense of others.

Despite agreeing in principle to provide relief alongside other lenders, Beijing has dragged its feet for the past two years. One aspect hampering Beijing’s response is coordinating the sheer number of Chinese institutions that have been lending to the developing world.

Zambia’s president said he hoped to see movement on the restructuring in the next few months. And despite her frustrations, Yellen reported recent “constructive” talks with a top Chinese economic official and said she was “encouraged that progress may become possible shortly.”

Let’s hope this optimistic view wins the day. After all, appropriately structured debt relief is in the interests of both debtors and creditors. And the outcome of Zambia’s talks will have an impact beyond its borders. Faced with rising borrowing costs as the U.S. Federal Reserve raises interest rates and high inflation, a series of defaults and instability across the developing world is possible. Governments heavily indebted to China are looking at Zambia as a test as to how they might be treated.

3. Like in the West, energy transitions in countries like South Africa will be challenged by vested political interests.

While in South Africa, Yellen traveled to the heart of the country’s coal-producing region to tout the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP).

Coal makes up approximately 85% of South Africa’s electricity needs, making the country the world’s 14th largest emitter of carbon. Its state power utility is inefficient, plagued by corruption and failing — robbing the country of the reliable power it needs to propel its economy forward and tackle the country’s poverty.

In 2021, the United States, UK, Germany, France and the EU committed $8.5 billion to help move South Africa away from coal through the JETP. After all, South Africa has an abundance of wind resources and is considered to have one of the top potentials for solar energy in the world. The funding, accompanied by private sector investment, will tackle infrastructure changes, as well as worker training.

But such grand efforts require committed partners. South Africa’s government is deeply reluctant to press the coal industry, one of the few sectors of the economy that shifted to black majority ownership since the end of apartheid and a key source of jobs. There is also suspicion of the private sector. Until recently, government policy inexplicably curtailed the amount of power private operators could produce — even as the country underwent 100 days of rolling blackouts last year. Officials are also pressing for more of the $8.5 billion to be in the form of grants, not concessional loans.

The JETP envisions government dollars “catalyzing” private sector investment into South Africa’s energy transition. But until South Africa creates an environment where the private sector can flourish, its energy transition is likely to remain stalled, with everyday South Africans suffering the most.

South Africans understandably see hypocrisy in the focus on green transitions, as Europe has kept coal burning to blunt the impact of Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine — even importing coal from South Africa. More broadly, Yellen noted that while 17 of the world’s top 20 climate-vulnerable countries are in Africa, the continent is only responsible for two to four percent of global greenhouse emissions. To help deal with climate adaptation and conservation, the Biden administration has said it intends to provide $1 billion to support African-led climate efforts.

4. Ending Russia’s war on Ukraine is the best way to help Africa’s economies.

In addition to China’s growing influence in Africa, the other country hanging over Yellen’s trip was Russia and the economic fallout from Vladimir Putin’s nearly year-long assault on Ukraine. Prior to the onset of the COVID pandemic and the Ukraine war, Africa boasted seven of the world’s top 10 fastest-growing economies. But those two world-changing events have kicked millions of Africans back into poverty and hunger.

Yellen said that Washington was providing support to mitigate the impact of rising food and energy costs on Africans. In Senegal, she said that a U.S.-Africa strategic partnership on food security is being established and touted U.S. efforts to stabilize global energy prices and reduce Russian revenues, which could potentially provide billions in saving to Africa’s oil-importing countries.

But Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s visit to South Africa, just days before Yellen’s, was a reminder that Russia is far from isolated in the developing world. Indeed, South Africa is scheduled to host Russian and Chinese naval exercises on the anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine.

While U.S. officials stress they are not asking African partners to pick a side, Yellen did not shy away from laying blame on Moscow: “… the actions of a single man — President Putin — [are] creating an unnecessary drag on Africa’s economy.”

Yellen even went so far as to declare that “the single best thing we can do to help the global economy is to end Russia’s illegal and unprovoked war in Ukraine” (emphasis added). That such a statement comes from the U.S. secretary of the treasury and former chair of the Federal Reserve should focus attention. Judging from the recent extensive back-and-forth over the transfer of tanks to Ukraine, Africans aren’t the only ones who need to hear the secretary’s words.