U.S.-Japan-Philippines triad builds on Washington’s strategy of bringing together allies and partners to ensure a stable region amid China’s aggression.

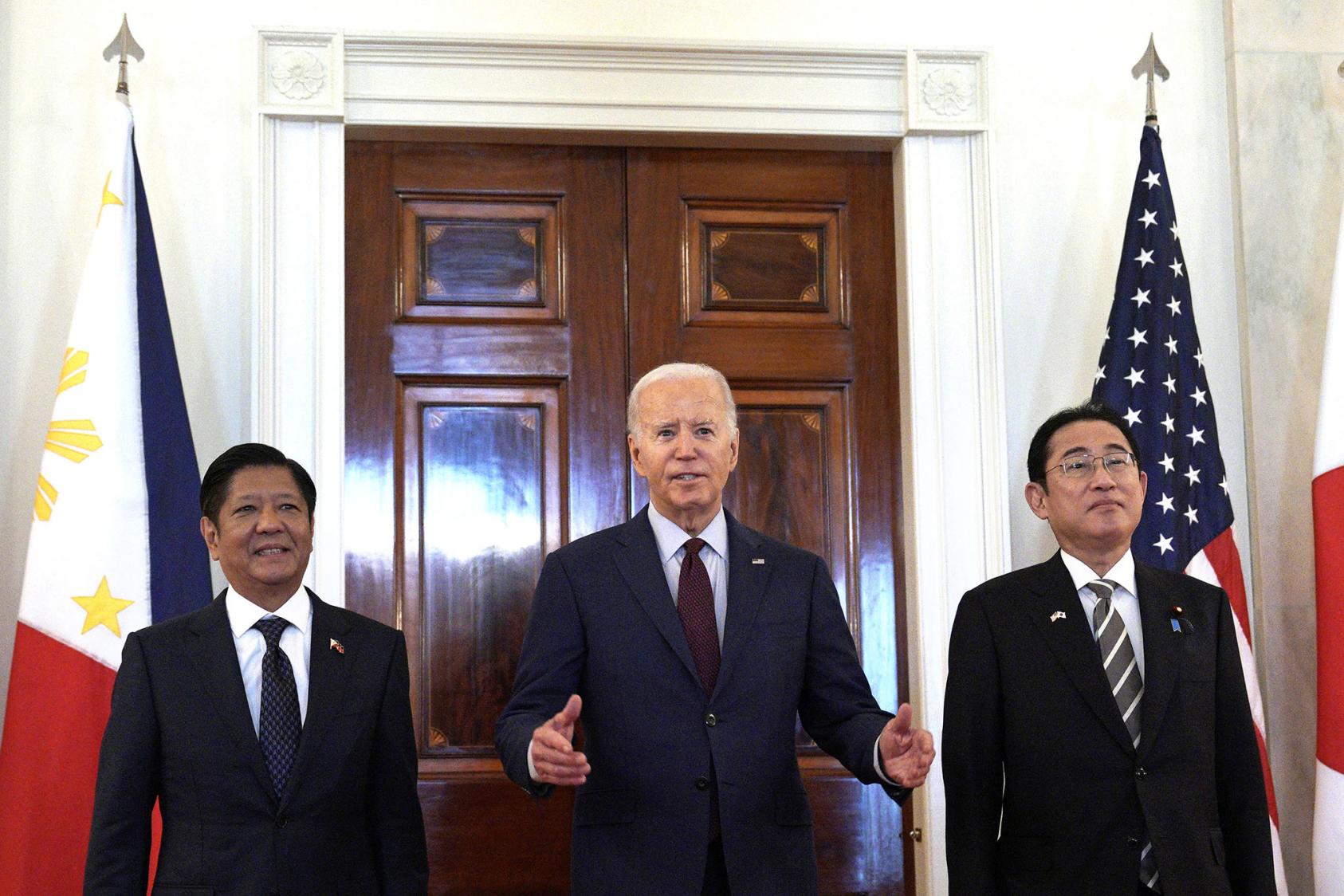

Last week, Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. stepped foot in the Oval Office for the second time in a year. Joining Marcos this time was Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, the leader of the United States’ most important ally in Asia and, arguably, the world. The Philippines has long been among a second rung of regional allies, so this first-ever trilateral summit marks Manila’s entrance as a leading U.S. ally working to maintain order and prevent Chinese revisionism in East Asia.

The meeting came amid rapidly increasing tension in the South China Sea, or West Philippines Sea as it’s called in the Philippines. The Philippines Coast Guard’s monthly resupply missions to the rusting BRP Sierra Madre on the Second Thomas Shoal, or Ayunyin Shoal, and China’s increasingly aggressive actions against Philippines vessels seeking to resupply the Philippines Marine detachment located there have become the drumbeat.

China has ratcheted up the pressure on these resupply missions over the past year, with the use of water cannons by Chinese Coast Guard vessels against much smaller boats — which have injured but not killed Filipinos — now established practice. Further escalation could quickly bring the United States and China into active conflict due to the U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty, and the United States has been clear that an armed attack on Filipino armed forces, public vessels and aircraft, including Coast Guard, in the South China Sea would invoke the treaty.

Japan is deeply familiar with the challenges the Philippines is facing to its sovereignty, as well as calculations related to its own defense treaty with the United States. Every day, Chinese ships and aircraft enter Japan’s territorial waters and airspace around the Senkaku Islands, which are administered by Japan yet claimed by China. The United States has also made clear that it is committed to the defense of Japan, including the Senkaku Islands.

The new triad is overdue in the making. All three countries are clear-eyed about China’s challenge to regional stability, with Japan and the Philippines each seeking to manage territorial disputes with China alone and with their U.S. allies. As three large, maritime democracies with shared interests and close bilateral ties on each leg of the triangle — they have simply been waiting for an opportune political moment. That moment has arrived with a U.S. president focused on alliances, a Japanese prime minister reinvesting in national security, and a Philippines president grappling with how best to address increasingly aggressive Chinese actions.

A Latticework of Allies and Partners

Last week’s summit was familiar for anyone watching how the Biden administration has approached the Indo-Pacific. While alliances have long been the bedrock of U.S. strategy in the region, the administration has worked assiduously to strengthen them by stitching bilateral alliances together to form a latticework of minilateral arrangements. Last week ushered in the U.S.-Japan-Philippines triad alongside the Indo-Pacific Quad, made up of the United States, Japan, Australia and India; the revamped U.S.-Japan-South Korea triad; and the U.S.-UK-Australian security partnership known as AUKUS.

The Philippines under President Marcos has been the X-factor. Since his inauguration in June 2022, Marcos has turned Philippines foreign policy on its head. It was a desperately needed pivot after former President Rodrigo Duterte’s efforts to push problems with China under the rug and distance the Philippines from its most important security partner, the United States. Marcos has confronted China through a proactive campaign designed to show the world China’s aggressive actions in the West Philippine Sea while building a robust network of new security partnerships with a revitalized alliance with Washington at its core. The seriousness with which the Marcos government has approached its national security and foreign policy agenda has built confidence in Washington that this is an alliance worthy of significant investment.

Japan, always one of the Philippines most important economic partners, has also quickly become one if its most important security partners. For Japan, which retains many self-imposed constraints on its national security policy from the post-World War II era, the Philippines has become a proving ground for a more assertive posture. The Japanese Self Defense Force’s response in 2013 to Typhoon Haiyan was the first major deployment of Japanese Self Defense Forces outside Japan since World War II. Japan’s first international defense sale following landmark reforms was radars for the Philippines. And its longstanding support to the Mindanao peace process has been the first Japanese presence in a conflict zone. Japan and the Philippines are currently finalizing a Reciprocal Access Agreement that will accelerate defense ties.

Multifaceted, Ambitious, Urgent

It is remarkable that rather than simply allowing these closer bilateral security ties to develop, both Japan and the Philippines have driven straight toward a trilateral security partnership that includes the United States. The speed with which this triad has developed demonstrates common purpose and familiarity, which is greased by the fact that both nations have longstanding alliances with the United States.

The summit was complemented by a host of ministerial-level engagements reflecting an ambitious vision for trilateral relations as well as announcement of a second-ever trilateral coast guard exercise following a quadrilateral naval patrol with Australia in the South China Sea just prior to the summit. It’s also notable that economic cooperation featured prominently during the week with a trilateral economic ministerial meeting and announcements on infrastructure, energy, critical minerals and other areas of investment. A suite of trilateral tracks of dialogues was announced covering a wide range of issues such as cybersecurity. For its part, Beijing has taken note of this emerging triangle, saying that it is aimed at China.

With tensions threatening to boil over in the West Philippines Sea, last week’s meetings could have not been better timed. Beijing’s increasingly hawkish actions threaten to destabilize the region at a time of great global volatility. In light of this, the U.S.-Japan-Philippines trilateral will need to play a central role in the networks of alliances and partnerships necessary for ensuring a peaceful and stable Indo-Pacific.