On the Issues: Tensions on the Korean Peninsula

USIP’s John Park discusses recent events on the Korean Peninsula and assesses the outlook for 2011.

December 27, 2010

.jpg) USIP’s John Park discusses recent events on the Korean Peninsula and assesses the outlook for 2011.

USIP’s John Park discusses recent events on the Korean Peninsula and assesses the outlook for 2011.

- What is the current situation on the Korean peninsula? What is creating such high tension between North and South Korea?

- Does China play a major role? What is Beijing doing to lessen tensions?

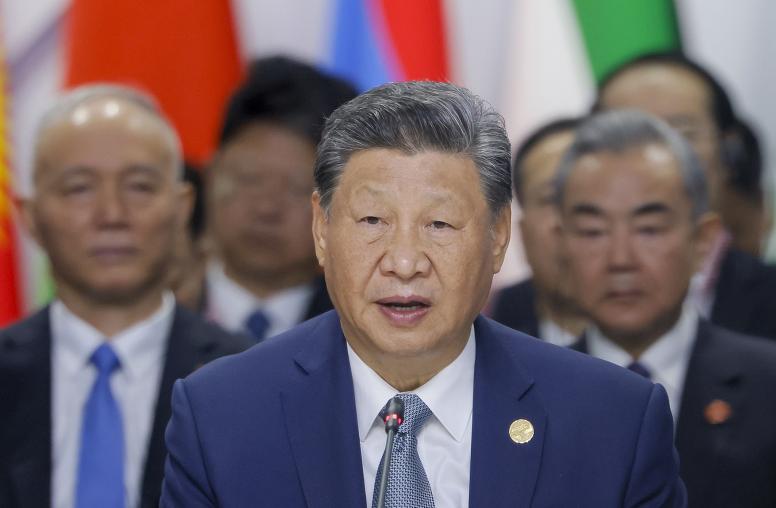

- As you look back on 2010, what has been the situation with North Korea? What do you see ahead in 2011 as the Chinese President comes to Washington, DC?

What is the current situation on the Korean peninsula? What is creating such high tension between North and South Korea?

The recent escalation of tensions on the Korean peninsula started after a North Korean artillery attack on South Korea’s Yeonpyeong Island on November 23. In response, South Korea conducted a joint naval exercise with its U.S. ally to send a firm message to Pyongyang that future provocations will not be tolerated. South Korea also conducted a live fire exercise on Yeonpyeong Island on December 20 to reinforce that point. North Korea had warned that should the South proceed with that exercise, the North would have no choice but to retaliate on a larger scale. In its own warning, South Korea countered that should the North retaliate, the South would carry out an airstrike against North Korean bases. Two days of bad weather ended up delaying the South Korean exercise, which may have given prevention efforts enough time to take effect.

Does China play a major role? What is Beijing doing to lessen tensions?

China is playing a major role in seeking to reduce tensions on the Korean peninsula. Sensing that reaction was dangerously feeding into reaction on the peninsula, China sent its top diplomat, State Councilor Dai Bingguo, to both Seoul and Pyongyang. In his respective meetings with South Korean President Lee Myung-bak and North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, Dai urged both Koreas to exercise restraint and resolve differences through dialogue and negotiations. In Seoul, President Lee urged China to use its influence to deal with North Korea’s behavior. South Korean and U.S. leaders have consistently been calling on China to rein in its North Korean ally. In Pyongyang, Kim Jong-il presented Dai with the North Korean version of events on November 23. The North Korean military had warned the South Korean side not to carry out its live fire exercise – even directed away from North Korea – because the North Koreans considered the area in which the South Korean shells would land to be their territorial waters. Since the South Korean military went ahead with their exercise, the North Korean military asserted that they had no choice but to retaliate with their artillery barrage to “safeguard our sovereignty.” South Koreans were alarmed that China did not condemn North Korea’s artillery attack. A combination of this brazen attack and China’s perceived siding with the North has created more unity among the South Korean public in viewing North Korea as a clear and present danger and China as part of the problem.

China’s major effort to lessen tensions was its call for an emergency meeting of the special envoys to the Six-Party Talks. Although China made it clear that it was not proposing a formal reconvening of the stalled Six-Party Talks, South Korea, the United States and Japan responded after trilateral consultations that they did not feel this was an appropriate way to address North Korea’s major provocation. In the hours leading up to South Korea’s exercise on Dec. 20, Russia, in close consultation with China, called an emergency session of the UN Security Council. Although the Council was deadlocked, the intense world media focus on the session, as well as other preventive diplomatic efforts, led to calls from many quarters for the two Koreas to back away from the brink of major escalation. After Pyongyang’s warning that the South Korean exercise could ignite a war, North Korean batteries remained silent in the end. Pyongyang issued a statement that it was "not worth reacting" to South Korea’s “reckless” military drills. Many analysts credit China with behind-the-scenes activities that resulted in North Korea backing down.

As you look back on 2010, what has been the situation with North Korea? What do you see ahead in 2011 as the Chinese President comes to Washington, DC?

North Korea has acted in a defiant manner in 2010 with little prospect that it will change its behavior in 2011. Rather than positively responding to South Korean and U.S. overtures for resuming denuclearization negotiations, North Korea has either carried out acts of provocation (like the sinking of the South Korean warship Cheonan in March and the Yeonpyeong artillery attack in November) or revealed prohibited nuclear construction (such as its advanced uranium enrichment facility, which it unveiled in November). Most of North Korea’s attention in 2010 was also focused inward as it dealt with managing a delicate hereditary leadership succession process, and achieving “kangsong daeguk” (strong and prosperous nation) goals by 2012 with a particular emphasis on economic development. These priorities are likely to dominate North Korean considerations and actions in 2011.

President Hu Jintao’s state visit to the United States on January 19 will kick off what is already shaping up to be a tense year. The consensus view among U.S. analysts is that the recent tensions on the Korean peninsula were largely defused by the Chinese as they made arrangements with the North Koreans to ensure President Hu’s smooth U.S. state visit. However, with both Koreas moving military assets to their forward bases along the demilitarized zone and conducting more exercises, the probability of an accident or misunderstanding has been rising significantly. The Korean peninsula cloud will loom over President Hu’s high-level meetings in Washington, D.C. and in what is looking to be a long and challenging year. Both U.S. and Chinese leaders will need to take the initiative in developing and implementing effective prevention strategies for the Korean peninsula as this tinderbox becomes drier and is confronted by more sparks. Relying on two days of bad weather to buy more time for preventive diplomacy is not a strategic option when tensions on the peninsula have already risen to the highest level since 1953.