Under congressional mandate, USIP has convened the bipartisan Task Force for Extremism in Fragile States to design a comprehensive new strategy for addressing the underlying causes of violent extremism in fragile states. But what is a fragile state? And how does state fragility in the Middle East, Horn of Africa and the Sahel threaten American interests? In this excerpt from the Task Force’s forthcoming report, we dive into the conditions of fragility and how they seed the ground for extremism to take root.

Each fragile state is fragile in its own way, but they all face significant governance and economic challenges. In fragile states, governments lack legitimacy in the eyes of citizens, and institutions struggle or fail to provide basic public goods—security, justice, and rudimentary services—and to manage political conflicts peacefully.

Citizens have few if any means of redress. As a result, the risk of instability and conflict is heightened. Throughout the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel, fragility is further exacerbated by growing youth populations. In the Arab World, about 60 percent of the population is below the age of 30, and youth unemployment, at just under 30 percent, is more than twice the global average.

The Fragility Study Group defines fragility as “the absence or breakdown of a social contract between people and their government.” The group is a joint project of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Center for New American Security and USIP, to improve the U.S. government’s approach to reducing global fragility.

In some states, governments lack the capacity to meet their citizens' needs. In many others, fragility is perpetuated by undemocratic and, often, predatory governance. In such countries, ruling elites exploit the state and enrich themselves rather than serve the citizens. They are willing to hold on to power by any means necessary: buying support through patronage, violently repressing opponents, and neglecting the rest. The resulting deep sense of political exclusion among citizens is aggravated by insecurity and shortages of economic opportunity. Repeated shocks—including the global financial downturn, the Arab Spring, and recurring cycles of crippling droughts—have roiled the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel in the last decade. Few states have weathered these shocks well because the conditions of fragility impede effective responses.

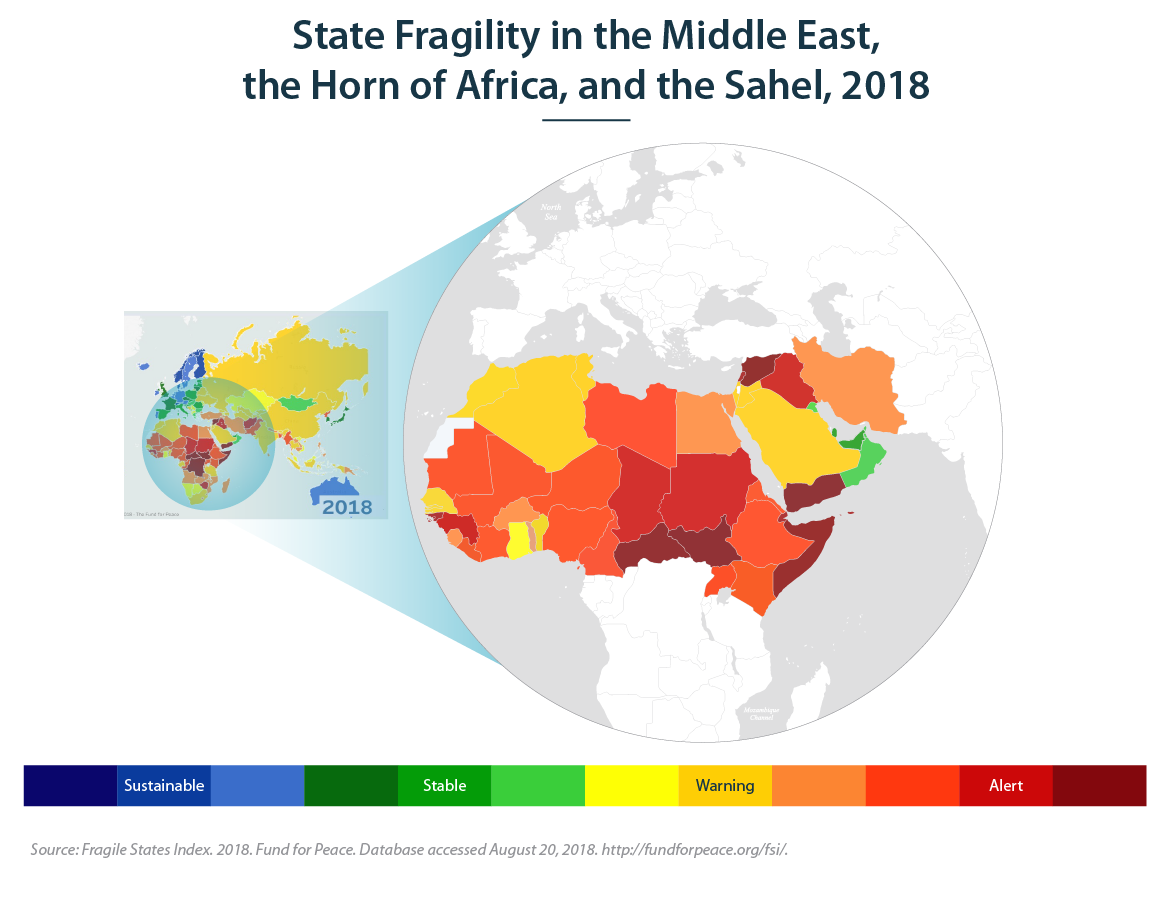

Almost every country in these regions falls outside the "stable" range of the Fund for Peace's Fragile States Index, occupying a spot somewhere between a "warning" and an "alert" level of state fragility. Other assessments of state fragility, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's States of Fragility report, reach similar conclusions.

And fragility in all three regions has deepened over the past decade. Since 2006, 30 countries across these regions have become more fragile, while only 19 have seen their fragility reduced. And the extent of these increases in fragility, on average, was greater than the decreases. Today, both the scale and the complexity of fragility are unprecedented.

Amid this ferment, extremists have launched their most daring onslaughts and made their greatest gains. Fragile states are no longer mere safe havens but instead are the battlefields on which violent extremists hope to secure their political and ideological objectives.