The recent territorial victories against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) are a significant achievement. However, terrorist groups like ISIS are not traditional enemies, and their strength cannot be assessed on traditional metrics. Thousands of fighters remain, and ISIS is intent on regrouping.

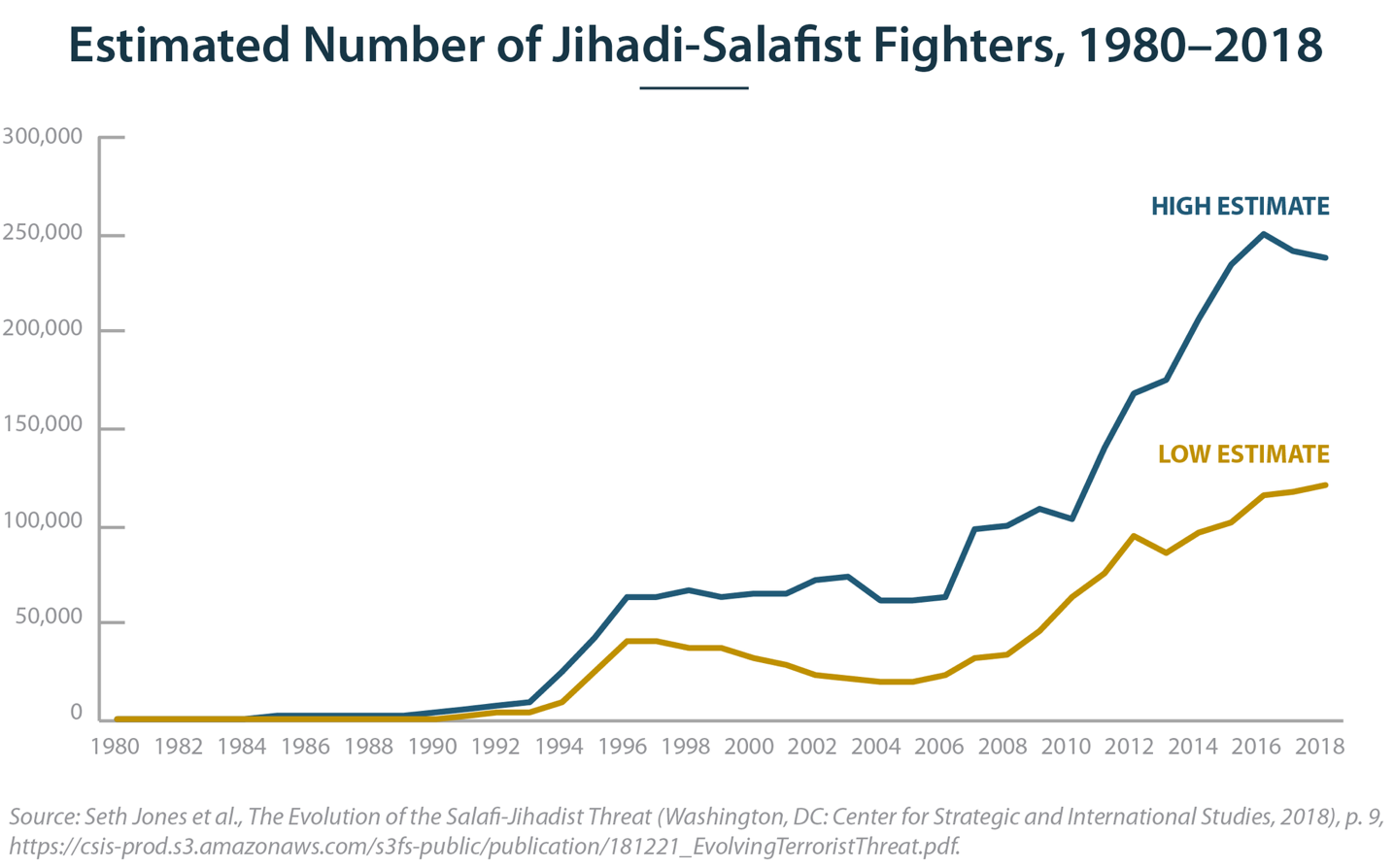

The complex battle against ISIS is a useful microcosm of the terrorist threat at large. Territorial defeats have not led to long-term destruction of terrorist groups. The number of extremists has actually expanded over the last decade.

Despite extensive counterterrorism efforts, at a cost of $6 trillion and 60,000 killed or injured, the number of terrorist attacks worldwide each year has increased five-fold since 2001. Sunni Islamist militant groups have grown nearly four-fold and are now present in 19 countries in the Middle East, Horn of Africa, and Sahel. Global terrorist groups in parts of Africa and Asia have expanded their abilities to strike local U.S. citizens, interests, and allies, stoke insurgencies, and foster like-minded networks in neighboring countries. Extremist groups are exploiting grievances and societal instability, and straining security forces to gain power.

Nearly all relevant U.S. policy tools, both hard and soft, are focused on dismantling terrorist networks, thwarting attacks, or stopping individual radicalization. These responses, even when successful, do little to prevent and often inadvertently help lay the groundwork for extremists to grow and thrive. This costly, reactive approach has diverted U.S. attention and resources from greater priority national security challenges. As long as the terrorist threat persists, our focus on responding to it will diminish our ability to respond to efforts by our competitors like China, Russia, or Iran in the region.

In this environment, Congress charged USIP with convening the bipartisan Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, chaired by former New Jersey Governor Thomas Kean and former Representative Lee Hamilton, to design a comprehensive new strategy for addressing the underlying causes of violent extremism in fragile states.

And next week, it will release its final recommendations to Congress and the administration outlining its proposed policy approach.

The recommendations are built on the following tenets:

- Extremism is inherently a political and ideological problem. Preventing extremism requires supporting local partners in addressing citizens’ needs while mitigating risk from outside actors.

- A successful preventative strategy does not include nation-building. The strategy relies on empowering local partners to safeguard their nations’ security and sovereignty.

- Extremism is a global problem and requires a global solution. The U.S. is well-positioned to lead efforts to focus the international community’s attention on prevention and catalyze donations. But a successful approach will require the participation and contribution of the international community and the private sector.

- Preventing extremism is less expensive than fighting terrorism. The proposed approach aims to reduce the need for costly and reactive strategies and tactics that are necessary once extremists take hold.

In 2004, after studying the circumstances leading up to the September 11 terrorist attacks, the 9/11 Commission, also led by Rep. Hamilton and Gov. Kean, concluded that future counterterrorism and homeland security efforts must be guided by “a preventative strategy that is as much, or more, political as it is military” in order to be successful in protecting against future terrorist attacks.

The military aspect of this strategy has long been realized. Fifteen years later, this report aims to lay the groundwork for fulfilling its political promise.