Different Wartime Memories Keep Japan and South Korea Apart

Civil society-based reconciliation efforts could help bridge divergent national memories.

The current state of relations between South Korea and Japan is, in the judgment of many observers, the worst since normalization in 1965. Despite decades of interaction, cooperation and even integration, relations between South Korea and Japan seem to have reverted to a dysfunctional status in which even the most basic forms of diplomatic intercourse present a challenge.

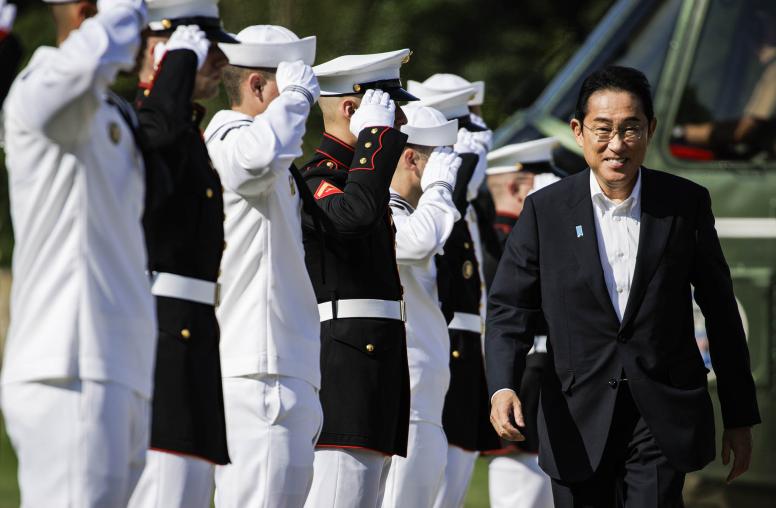

New leadership in both countries, however, provides hope for change. The governments of South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio have made clear commitments to reversing the downturn in relations and are engaged in diplomatic efforts to resolve issues of wartime history.

There is also a geopolitical dynamic at work that might help propel change. The United States has long sought to bind its two Northeast Asian security allies into a trilateral construct, recognizing the pragmatic reality that cooperation is essential for it to be able to fulfill its defense commitments to both countries. The restoration of normal relations between Japan and South Korea is now seen as essential to the success of U.S. efforts to assert a values-driven purpose to its presence in the Indo-Pacific. The failure of two U.S.-allied democracies to cooperate creates a hole in this strategy, whether it is the elevation of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue to a pseudo-alliance or Japan’s idea of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.” It creates an opportunity for China or Russia to drive wedges between the United States and its allies.

All of this has acquired even greater urgency with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as the United States and Europe seek to rally allies across the globe, and particularly in Asia, to a common cause. If this is, as they assert, a struggle between democracy and authoritarianism, the visible gap between Japan and South Korea is a glaring problem.

The Power of Narratives

The realignment of domestic political and geopolitical factors in favor of reconciliation, while essential for any breakthrough in relations, does not assure success.

The reason for this wariness is familiar to scholars of Korea-Japan relations and wartime historical memory formation. The downturn in Korea-Japan relations is clear evidence of the power and persistence of the historical narratives about the wartime period constructed in these two countries, as well as in the United States, China and other participants in the war in Asia, and their centrality to the formation of national identity in each country. Modern nationalism, shaped by the struggle against colonialism and imperialism and by the creation of the postwar systems of the Cold War, remains anchored in World War II and its aftermath. We see that in Europe today, where Russian nationalism and imperial nostalgia is rooted in a narrative about World War II. And we see how the war in Ukraine today is framed by both combatants in the language, however disparate or distorted, of that war.

This essay describes the dilemma of how Japan and South Korea have developed separate memories of the wartime period and the colonial rule which preceded and shaped the experience of war, and the issues of historical justice that remain a legacy of war. It offers potential ideas for civil society-based reconciliation efforts that could help bridge the disparate national memories.

The Problem of Separate Memories

Of all the relationships that emerged from World War II, none is more persistently fraught by the past than the one between South Korea and Japan. Japan’s wartime past in Southeast Asia is far more tractable. Even the China-Japan relationship, which has a long rivalry with periods of cooperation, engagement and contestation, is less emotionally strained, partly due to Japan’s recognition of its deep cultural legacy from China. But in the case of South Korea and Japan, there is the combustible mixture of colonialism and war, and of a cultural interaction that threatens the sense of national identity formed in both countries. Neither can acknowledge the mutual debt and interwoven ethno-national evolution without challenging their own national identity.

In our Stanford study of wartime memory formation, Gi-Wook Shin and I argued that the barrier to reconciliation lay in the existence of fractured national narratives, both within and among the participants in the Pacific War. Our study examined the impact of formal education, mainly through textbooks; popular culture, mainly through dramatic film, though other media such as television and literature are equally powerful; and elite opinion in shaping those narratives. We found that the clash in narratives came more from the distinct focus of each national tale than in divergent historical accounts of events, though those differences exist as well.

Also, after several years of teaching a class on wartime history memory formation at Stanford, with rich participation of students from the United States, China, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Australia and Southeast Asia, I have found that, unlike the contrast between Chinese, U.S. and Japanese wartime narratives, there is such a profound difference in focus between South Korea and Japan that it amounts to almost completely separate spheres of national memory about the wartime period. There is almost no place where the national narratives, and the identity formation that flows from them, overlap, even to offer contending accounts of the same wartime events.

South Korean Wartime Memories

For South Korea, the contemporary national memory of the wartime period is entirely framed by Japanese colonial rule. Korean textbooks, literature, film and other forms of popular culture explore the experience of colonial rule in painful detail. In recent years, Koreans have tackled the sensitive matter of those who collaborated with Japan, although this is still acknowledged only within the context of heroic resistance.

Sometimes, the broader global war appears like a scenic backdrop in a painting. There are some odd exceptions, such as “My Way,” a film based on a book, which tells the story of Yang Kyoungjong, who ended up fighting for the Imperial Army, the Red Army and the Wehrmacht. But Korean historical narratives make almost no reference to the war that raged beyond the country’s borders. That is the case despite the fact that Japan’s drive for broader imperial conquest shaped its intervention into Korea and determined every aspect of its colonial administration, from at least the early 1930s onward, if not before.

Even the involvement of Koreans in the war itself — other than as forced laborers or sexual slaves — is barely acknowledged, except as an issue of collaboration with the colonial master. Korean soldiers fought in the Japanese ranks in the war, guarded Allied POWs in camps in what is now known as Myanmar and died in the U.S. air war. But these experiences are almost completely absent from South Korea’s national memory formation.

South Korean high school history textbooks, as we found in our Stanford comparative study, focus on accounts of colonial rule. There is some minimal acknowledgement that the mobilization of forced and other labor was linked to the needs of the war effort. There is almost no narrative account of the war, even of the Sino-Japanese war or the takeover of Manchuria, which was tightly linked to the annexation of Korea.

A recent wave of Korean popular films is also powerfully shaping national memory there. For example, “Battleship Island,” a popular 2017 blockbuster action film, tells the story of the wartime revolt of Koreans forced to work at the Mitsubishi coal mines on Hashima Island, a UNESCO World Heritage memorial site. The film not only offers a moral tale of resistance to forced labor, but also weaves in a judgment of those Koreans who collaborated with the Japanese. Similarly, we see this history conveyed in “Mal-Mo-E: The Secret Mission,” a 2019 historical drama about the Korean Language Society under colonial rule and its struggle to preserve and document the Korean language. The film vividly explores Japan’s efforts to exterminate Korean culture and celebrates the heroic Koreans who sought to preserve it, again in the face of collaboration.

Japanese Wartime Memories

In stark contrast, Japanese wartime memory, even that formed by conservative nationalists, has created an odd narrative black hole around Korea. There is almost no discussion of Korea’s experience of colonial rule in Japanese high school textbooks, other than some limited accounts of forced labor and “comfort women.” By contrast, Japanese textbooks include extensive accounts of the unfolding of Japanese imperialism in China, from the takeover of Manchuria through the Sino-Japanese War.

When it comes to postwar Japanese cinema, Korea is again virtually absent in stories of the war. Japanese cinema focuses on the Pacific War with the United States and the United Kingdom, and to a lesser extent the war with China, including the takeover of Manchuria. The readiness to confront the experience of the war in China is more evident in the films of the immediate postwar period, when progressive narratives were more prominent. This is exemplified perhaps best by the magnificent epic “Ningen No Joken” (“The Human Condition”).

But Korea barely shows up. In an exchange with this author, Yale University professor Aaron Gerow noted that “when it comes to [Japanese] films made after 1945 there are only a handful of films that are set in or significantly deal with colonial Korea.” One exception that stands out mostly because it is so unusual is a 2012 film, “Michi — Hakuji no Hito” (“Takumi: The Man Beyond Borders”), Gerow noted. It takes place in the colonial era and celebrates a Japanese man who sought to preserve traditional Korean culture.

A Need for Civil Society-Based Reconciliation

The creation of separate spheres of memory about the colonial and wartime era operates as a daunting barrier to reconciliation. Political drivers and geopolitical forces may create opportunities for reconciliation. But in democratic societies like South Korea and Japan, there must be an effort to create some shared understanding of the past. Without that, reconciliation will not be sustainable.

Efforts to improve South Korea-Japan relations should not be confined to the realm of diplomatic negotiations between the officials of the two foreign ministries. Civil society-based reconciliation is essential to provide the foundation for sustaining whatever efforts are made by political leaders and government officials. Without broader efforts to construct bridges between the spheres of separate historical memory, the tentative moves will inevitably collapse under the weight of public opinion.

Academic research can contribute to laying that groundwork. Collaboration between scholars in Japan, South Korea and the United States on comparative studies of war memory, even on specific events and issues in the wartime period, is essential. Scholarly dialogues, along with civil society organizations, can address and perhaps begin to correct the problem of separate memories. Similarly, there is a great need to use popular culture as a tool to create shared memories, such as joint dramatic South Korea-Japan television productions that address historical memory issues. And governments can offer support — especially political and financial — for civil society reconciliation.

The following ideas for civil society-based reconciliation efforts were generated by previous dialogues that Stanford organized among Chinese, Japanese, Korean, European and U.S. scholars and non-government activists.

History Textbooks

Although joint history textbooks have been long discussed, based on the model of the Franco-German joint textbook, this goal is illusive and unattainable. A more realizable goal is the creation of supplemental teaching materials that offer students a comparative approach. The Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education (SPICE) has already done this, based on the Divided Memories program, for U.S. high school teachers. Versions of this in Japanese and Korean could focus more on the comparison between the narratives in both countries.

Media Dialogues

Media is a major driver of historical memory and, unfortunately, also a significant source of distorted understandings of the past. Korean and Japanese journalists, from all mediums (broadcast television, print, social media), have almost no opportunities for interaction, not only with each other but also with historians who can offer more dispassionate views of the past.

One idea is to bring journalists and historians together in organized forums where history scholars present views on historical events to journalists from print, broadcast and online media. Scholars could make presentations on the results of comparative research on textbooks, historical research on specific events and efforts at reconciliation. The participants could include media and scholars from other countries, including China, the United States and Europe.

Youth Exchanges

Based on the model of Franco-German student exchanges, programs to bring Korean and Japanese students together could be created or expanded, with educational components. A Korean nongovernmental organization has done this for many years — creating summer camps where youth engage in visits to wartime historical memorials and hold dialogues.

History Teachers’ Dialogues

Japan and South Korea could create opportunities for history teachers from both sides to participate in a one-week professional exchange program. Participants would be able to interact with their colleagues on various historical issues and bring back an appreciation and understanding of each other’s perspective to their classroom.

Museum Exchanges

A similar dialogue could be established among museum directors and those who create the narratives for museums dealing with wartime issues, including exchanges with museum personnel in the United States and Europe. Given the important role that museums play in transmitting historical narratives, such dialogue and collaboration among museums would complement the other educational initiatives carried out in school settings. The long-term goal might be to create a model museum that promotes a shared historical heritage between South Korea and Japan.

These are by no means all the potential avenues for civil society engagement on historical memory. And in all cases, they require not only the presence of civil society organizations but also the decision of political leadership to provide the context, and support, for such engagement.

Daniel Sneider is a lecturer in East Asian studies at Stanford University.