Achieving a More Durable Japan-South Korea Rapprochement

To build durable goodwill, a deliberate and inclusive approach will be required by the leadership in Seoul and Tokyo.

The winds of political change swept through South Korea in early 2022. Yoon Suk-yeol, a conservative and former prosecutor general, triumphed in the presidential election. As the incoming president seeks a new direction for Seoul’s foreign policy, perhaps the most politically fraught and sensitive part of his agenda is improving South Korea’s frayed relations with its former colonizer, Japan. Better relations will benefit both countries, but their leaders will need to be careful about how they go about improving relations if they are to create a durable sense of goodwill. They will need to listen to dissident voices, look at their history in new ways and convince the United States to play a productive role.

Past Efforts to Improve Relations

Efforts to improve relations with Japan have been a hallmark of conservative foreign policy in South Korea for decades. It was under the development-minded dictator Park Chung-hee that Seoul and Tokyo first managed to normalize relations and put aside some of the lingering resentments from the colonial era. After the two signed the Treaty on Basic Relations in 1965, Japanese aid and investment flowed into South Korea, bolstering the country’s high growth rates during the 1960s and 1970s. Chun Doo-hwan, the leader of a military junta that seized power after Park Chung-hee’s assassination on October 26, 1979, took further steps to improve the relationship, including a visit to Tokyo that led to both improved security ties and an apology from Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone for the “great sufferings” inflicted upon Korea. And it was Park Chung-hee’s daughter, Park Geun-hye, who as president of South Korea reached an agreement with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2015 to “finally and irreversibly” resolve the comfort women issue while also signing the General Security of Military Information Agreement to facilitate intelligence sharing.

For the most part, efforts by conservative South Korean leaders to improve relations with Japan have been pragmatic but unpopular. They prioritized security and economic issues while ignoring their critics. But this approach has never produced the kind of durable goodwill between South Korea and Japan that exists among NATO countries. Instead, these efforts were met with ongoing criticism for failing to settle territorial disputes and resolve claims for compensation by Korean victims of Japanese colonialism. South Korea’s last significant agreement with Japan — the 2015 comfort women agreement — unraveled quickly after progressive reformer Moon Jae-in was elected president in 2017. Moon’s annulment of the agreement and the South Korean Supreme Court’s 2018 decision requiring Japanese companies to pay compensation to World War II-era forced labor victims caused relations between Tokyo and Seoul to deteriorate swiftly. The Abe government placed new restrictions on technology exports to South Korea resulting in local boycotts of Japanese goods and efforts by Seoul to reduce its economic reliance on Japan through greater research and development spending.

Yet improving ties between Seoul and Tokyo remains an important task. Japan and South Korea share a set of core values and interests that differ from those of many other Asian countries. They are committed to preserving democratic political institutions, fair elections, and freedom of speech, assembly and religion — none of which are upheld widely in the Asian region. While they face a number of common problems, they are also both economic powerhouses with considerable soft power and cultural influence. As authoritarian countries in the region — especially China, Russia and North Korea — become increasingly supportive of each other, discord among the region’s democracies may end up further empowering its assertive dictatorships. Moreover, in an era of supply chain disruptions and growing economic nationalism, restoring Japan and South Korea’s frayed trade relationship is critical to the global economy.

While a great deal may hinge on Yoon’s efforts to restore Japan-South Korea relations, reaching a settlement that is more durable and popular than those reached by his conservative predecessors is also critically important. It makes no sense for Seoul and Tokyo to spend months or even years hammering out agreements that will be disregarded when the political tide shifts again. Yoon cannot adopt the same approach as previous conservative presidents and expect a different result. A renewed effort to improve relations with Japan will have the best chance of succeeding if it does the following:

Include the Opposition

Although South Korea has perhaps the most vibrant democracy in Asia, its foreign policymaking has never been characterized by bipartisanship. Progressive administrations like those of Kim Dae-jung and Moon have pursued rapprochement with North Korea despite noisy opposition from conservatives, while conservatives have opted for more hawkish approaches.

South Korea’s Japan policy has followed the same pattern and this needs to change. One of the main reasons that the 2015 agreement failed was that it ignored some reasonable criticisms from the opposition. Defenders of the agreement have argued that Park Geun-hye’s government did its best to listen to victims and point out that 34 of the 46 surviving comfort women accepted compensation arranged by the agreement. But some comfort women advocacy groups and members of the opposition Democratic Party opposed the deal because it enabled Japan to evade the conditions laid out by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights for fully resolving the issue. In particular, the agreement did not require Japan to acknowledge that the comfort women system had constituted a form of sexual slavery. Others noted that compensation provided by the agreement did not come directly from the Japanese government and that Abe did not apologize directly to the comfort women. Popular opposition threatened to unravel the agreement even before Park Geun-hye’s scandal-ridden presidency collapsed. Park Geun-hye’s failure underscores the need for Yoon to consult with the opposition and incorporate some of their views into any new agreements with Tokyo.

Currently, Yoon calls for a more “forward-looking” relationship with Japan — by which he apparently means downplaying historical disputes and focusing on improving economic and security ties. But Yoon should remember that neglecting the underlying historical issues was a key reason that previous efforts to improve relations with Japan failed. His willingness to include representatives of forced labor victims in an advisory council set up to help resolve the forced labor dispute with Japan is encouraging. But their boycott of the third advisory meeting suggests that incorporating opposing views and resolving historical grievances will be difficult. Yoon will need to keep the political costs and benefits of his foreign policy decisions in mind. His election victory was an extremely narrow one (less than 1 percent of the vote) and it will not take much to swing the political pendulum in the other direction.

Incorporate More Nuanced Historical Understandings

An important reason that negotiations between Japan and South Korea over historical issues are so difficult is how they are framed. The dominant narrative in these discussions has been one of Korean victimization and Japanese aggression. Recently, however, a number of historians have contended that this is not the only way that Japan’s wartime atrocities can be understood. For instance, the comfort women issue does not have to be strictly looked at as an instance of Japanese aggression against Korea. Much can also be learned from understanding Japan’s wartime system of sexual slavery as gender-based violence. Because gender-based violence and the patriarchal social structure that abets it are such prominent phenomena in world history, using this framework can allow Japanese and Koreans to deal with the past in a way that emphasizes common human faults and is less accusatory.

Other historians have investigated the environmental consequences of Japanese rule in Korea. Their work has linked Japanese colonialism in Korea to more universal aspects of the human experience such as governance of land and natural resources.

South Korean policymakers should try to incorporate these new perspectives into discussions of Japanese colonialism. It might afford a way for Japan to acknowledge its past wrongdoings without inciting the kind of nationalistic backlash that such discussions usually produce.

Japanese conservatives tend to see any discussion of their country’s history of colonial violence as an effort to humiliate Japan. Introducing new perspectives might enable them to respect rather than ignore the past.

Invite the United States to Play a Constructive Role

No country has more to gain from rapprochement between Japan and South Korea than the United States and no country has more leverage over Tokyo and Seoul. Yet Washington has not fully understood how security and historical issues are interrelated in Northeast Asia. U.S. officials have frequently stressed that their South Korean counterparts should put historical and territorial disputes aside and focus on security issues. To South Koreans, however, the two cannot be so easily separated. Japan’s history of brutal colonialism in Asia remains a source of bitterness and anxiety for South Koreans and many fear Japan’s potential military power as much as China or North Korea.

Washington needs to be more attuned to South Korea’s perspective. It should, as then U.S. President Barack Obama attempted to do during his 2014 visit to Seoul, encourage Japan to deal honestly with its past while emphasizing to South Koreans that once this happens Japan’s wartime misdeeds should be forgiven. At the same time, Obama, like other U.S. presidents, was reluctant to put any real pressure on Japan when it came to dealing with historical issues or improving ties with South Korea. Washington needs to make the case more strongly to Tokyo that resolving these issues will foster greater trust in Japan and strengthen the security of the United States’ democratic allies in the Pacific.

Bringing about such a shift in Japan’s outlook might take considerable time but in the shorter run, Washington can help make progress on more modest trust-building measures. It should immediately persuade Japan to remove its export controls on chemicals used by South Korean high-tech firms and fully restore South Korea’s trading privileges in exchange for South Korea returning Japan to its own trading white list and encouraging an end to boycotts of Japanese goods. Japan’s reasons for removing South Korea from its white list never seemed to be much more than a petty response to the failure of the comfort women agreement. Pressuring Japan more strongly to reverse these decisions is critical not only to the healing process between South Korea and Japan but also to the troubled global economy.

Expand Professional Exchanges that Are Issue-Oriented and Focused on Common Problems

People-to-people exchanges between Japan and South Korea have persisted even as political relations between the two countries deteriorated. Despite their differences, Japan and South Korea face a number of similar challenges outside of the security realm. They both have aging populations and low birth rates; they both have suicide rates that are among the highest in the world; they both face growing social discontent due to gender inequality; they share a common interest in the economic development of members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); and they are both impacted by environmental problems that have accompanied Asia’s rapid industrialization. Thus far, there has been limited but promising collaboration on some of these issues. Even during the fall of 2019, when tensions over the comfort women agreement and trade issues were at their zenith, social experts from the two countries managed to hold a joint conference on population issues in Seoul. But other promising ventures, such as the Japan-Korea Environmental Policy Dialogue, seem to have fallen off since 2019. These types of activities need to be resumed, expanded and given more attention by the media and public officials.

Jointly developing knowledge and solutions on specific problems will create a sense of common purpose that may partially replace the antagonism and mistrust that currently prevail. If these exchanges lead to more fruitful collaborations, it can also foster a sense of shared accomplishment and mitigate more narrowly nationalistic visions of the relationship.

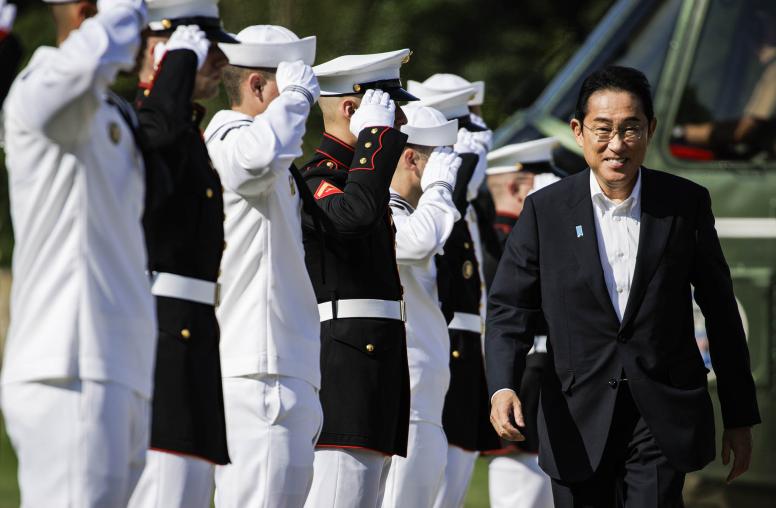

Yoon may find his Japanese counterpart, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, receptive to holding talks and improving relations as both countries face growing Chinese regional ambitions and must cooperate to grow their economies in a time of global turmoil. Yoon’s real challenge, however, will be initiating a rapprochement that is based on more than expediency. He needs to improve relations with Japan in a way that has widespread support in both societies and can replace the current mistrust with genuine goodwill. Of course, Yoon cannot do this completely on his own; he will undoubtedly need a more self-reflective and cooperative Japan. Ultimately, however, Yoon’s objective should be to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. Only through an inclusive approach that finds new ways of reckoning with history and new avenues for building common ground will lasting success be possible.

Gregg A. Brazinsky is a professor of history and international affairs at the George Washington University. He currently serves as the director of the Sigur Center for Asian Studies and the Asian Studies Program. He is the author of Nation Building in South Korea: Koreans, Americans, and the Making of a Democracy (UNC Press, 2007) and Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War (UNC Press, 2017).