Three Things to Know About China-India Tensions

While neither side wants escalation, their actions risk exacerbating a classic security dilemma, leading to costly, high-stakes competition.

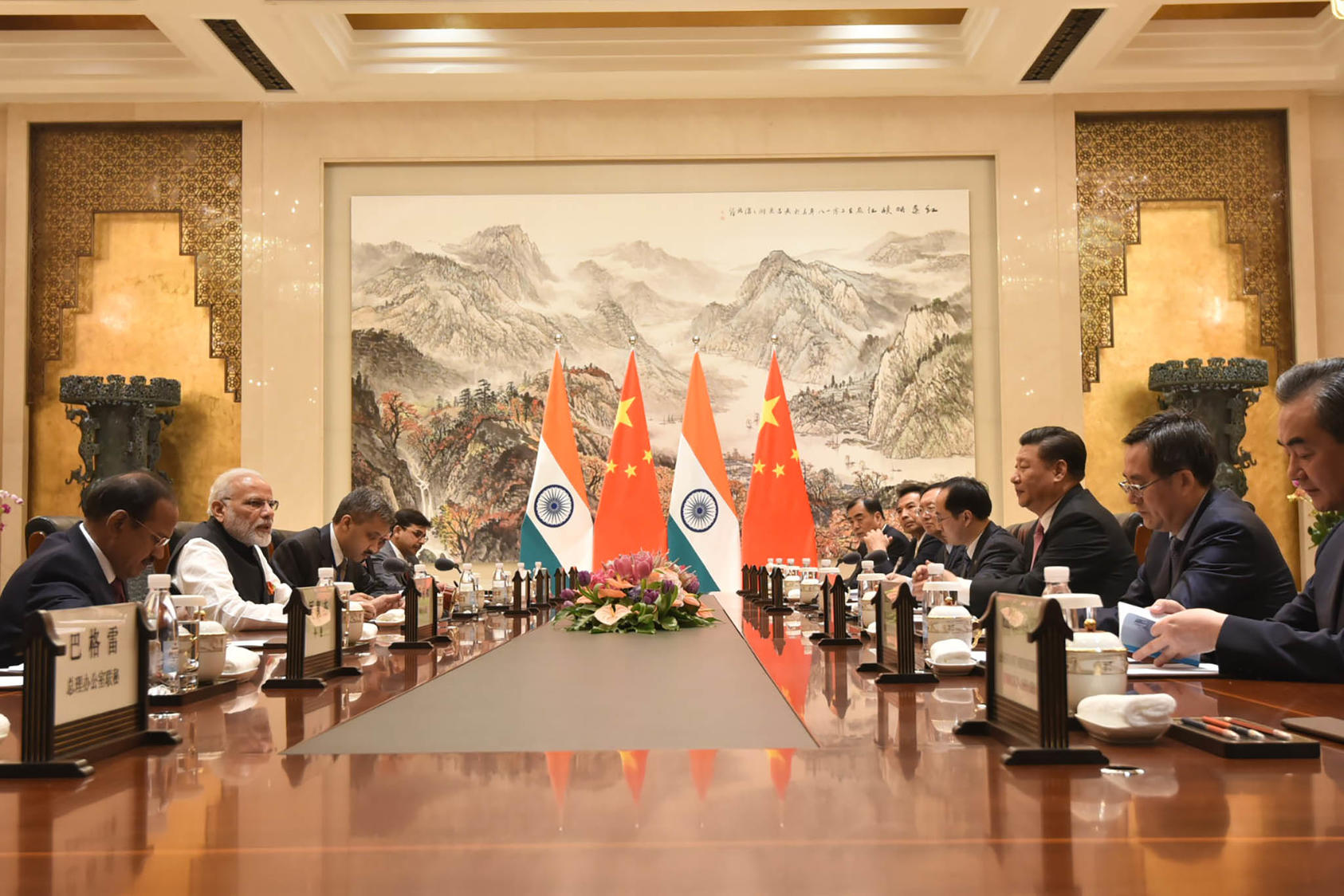

Relations between the two Asian giants have soured over the last decade, particular following a 2020 border brawl between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley. While there are credible concerns that these nuclear powers’ ties are trending in the wrong direction — particularly as both sides continue provocative actions — neither Beijing nor New Delhi wants to see an escalation toward a more serious conflict. For its part, the United States has sought to deepen its security and economic relationship with India as the U.S.-China rivalry intensifies and considers it a vital partner in Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy. But don’t expect India to simply follow the United States lead, as New Delhi remains hewed to its policy of nonalignment amid rising major power competition and an emerging multipolar world.

USIP’s Andrew Scobell and Daniel Markey explain how each side views the souring of relations, what the near-term outlook is for their bilateral ties and what it all means for the United States.

How do Beijing and New Delhi, respectively, perceive the rise in tensions?

Scobell: For the present, China seeks to maintain a cordial working relationship with India, setting aside contentious issues such as the unresolved border dispute while it plays a long game to advance its interests. For the foreseeable future, Beijing desires to keep New Delhi contained in a geostrategic South Asian box with the lid on tight, while China conducts business-as-usual diplomacy and commerce with India. Chinese leaders perceive India as an over-sized middle power with great power pretentions.

That said, in recent years Beijing has taken New Delhi more seriously as a threat to national security and an impediment to China taking its rightful place as the dominant Asian power on both the landmass and littoral of a vast continent. Consequently, China has — among other things — doubled down on its long-standing “all weather relationship” with India’s South Asian nemesis Pakistan. This Beijing-Islamabad continental axis includes sizeable and enduring military and economic dimensions.

China considers India, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, intent on stirring up trouble along their common Himalayan border and collaborating with other powers to contain China’s rise and counter China’s growing presence in the Indian Ocean region. Moreover, Beijing has noticed New Delhi’s burgeoning economy, expanding military capabilities and is still absorbing the psychological impact of India overtaking of China as the world’s most populous state in mid-2023. China has also taken note of India’s expanding security ties with the United States and its membership in the reenergized Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (commonly called the Quad) along with Australia, Japan and the United States.

Nevertheless, Beijing welcomed New Delhi — along with Islamabad — into the China-dominated Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2017 and China and India are founding members of the BRICS forum. Yet, India stands out as the most important developing world state to opt out of Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy initiative, China’s Belt and Road program launched with great fanfare in 2013.

Markey: India’s relations with China have suffered a series of blows over the past decade punctuated by the deadly border skirmishes of 2020. Since then, the two sides have remained locked in an “abnormal” state of relations. This is far from the trajectory that Indian policymakers anticipated a decade ago when Prime Minister Modi came to power. Then, top Indian experts and seasoned policymakers foresaw a future of balanced ties between India and all other world powers, including China. Indeed, Modi and his team perceived China as an economic partner essential for India’s growth and development.

That Indian impulse remains powerful even now; over the past year the Modi government appears to have held out hope for a return to more normal relations with China. Indian diplomats believed that military-led talks with their Chinese counterparts on the contested border would deliver enough progress to enable a resumption of summit-level diplomacy with China in 2023, a year of high-profile diplomacy in which Modi was slated to host the SCO, attend the BRICS Summit in South Africa and host the G-20. However, Indian expectations went largely unmet. New Delhi downgraded the SCO to a virtual summit at the last minute, Modi and Xi had only cursory and apparently unproductive discussions in Johannesburg, and Xi snubbed India by electing to skip the G-20 altogether.

What is the near-term outlook for the relationship?

Markey: The China-India diplomatic stalemate of 2023 could easily persist throughout 2024. Modi has strong incentives to hold a tough line with Beijing. Politically, Modi faces an upcoming national election campaign in which India’s opposition party leaders have already criticized his handling of relations with China. Having cast himself as a staunch nationalist, Modi cannot afford to look weak before the Indian electorate. Strategically too, Indian leaders must fear that even the appearance of concessions to China would be as likely to encourage further bullying as to buy stability.

This does not mean India relishes its ongoing contest with Beijing. New Delhi simply feels that the ball is in Beijing’s court: India has been forced to respond to China’s military provocations along the Line of Actual Control and, more generally, to an array of Chinese political, economic and military intrusions into India’s traditional sphere of influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. For now, given the asymmetry of power that favors China, the best New Delhi can do is to redouble its investments in border defenses and cultivate closer ties with outside powers — above all, the United States — with a shared interest in deterring Chinese aggression. Yet even India’s defensive moves risk exacerbating a classic security dilemma with China, prompting an ever more costly, high-stakes competition.

One potential bright spot in this otherwise gloomy picture came in the most recent 20th round of military talks. The two sides reportedly agreed to avoid provocative actions during the brutally cold Himalayan winter and to discuss options for mutual reductions in border troop levels during the spring and summer.

Scobell: While China looks to manage its often testy and sometimes volatile relationship with India, the distrust and suspicion that has cast a dark shadow over Beijing-New Delhi ties for six decades — since the 1962 border war — have persisted and been reinforced by more recent bloody border clashes. Whereas in past decades Sino-Indian tensions and the climate of confrontation were largely geographically confined to their remote landlocked borders, the arena of confrontation has expanded to include the maritime realm — in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Moreover, both China and India now compete for influence and status on the global stage, including for leadership of Global South countries. All this suggests that bilateral relations are unlikely to improve significantly in the foreseeable future.

What does this mean for U.S.-China rivalry and the U.S.-India relationship? And how should Washington respond?

Scobell: Washington should look to strengthen its partnership with New Delhi in ways that reassure India and deter China. While there are limits to the extent to which U.S.-Indian security ties can strengthen because of New Delhi’s strong tradition of nonalignment there is nevertheless room to enhance strategic cooperation in ways that benefit both the national security of each democracy as well as strengthen the stability of the Indo-Pacific region.

Washington can meanwhile make clear to Beijing what U.S. goals and interests are vis-à-vis New Delhi. While Chinese leaders may be reluctant to accept such messages at face value, without articulating objectives and priorities, the United States risks Beijing drawing its own uncontested conclusions about U.S. intentions. Clear messaging and constant communication between the United States and China has never been more important. This is true not only in the broader context of U.S.-China global strategic competition but also in the more bounded space of South Asia.

Markey: The Biden administration clearly perceives closer ties with India as a cornerstone in its strategy for geopolitical competition with China in the Indo-Pacific. Yet it is India’s sense of vulnerability to Chinese aggression that has, more than any other factor, led New Delhi to embrace Washington’s offer of strategic partnership. The American liberal democratic worldview, U.S. global leadership and “Western values” all hold rather limited appeal to New Delhi’s current crop of leaders. To the contrary, they would prefer a global order defined by multipolarity in which India could safely sidestep geopolitical competition between China and the United States while navigating its own way to global leadership.

U.S. policymakers should understand India’s distinctive perspective on competition with China. Although India and the United States both see China as a strategic problem, they view it through different lenses of national interest and ideology. India’s leaders are cognizant of the risks they run by a festering border dispute with China and remain uncomfortable with how that insecurity is forcing India into greater dependence on Washington. Such insights should inoculate U.S. policymakers from the false impression that India is eagerly joining a U.S.-led coalition against China and should introduce caution into Washington’s expectations for an alliance-like partnership with New Delhi.