China’s Alternative Approach to Security Along the Mekong River

To gain legitimacy with Mekong countries, China’s Global Security Initiative must first address its own role in security problems.

Editor's Note: The following article is part of a USIP project, "Tracking China's Global Security Initiative." The opinions expressed in this essay are solely those of the author and do not represent USIP, or any organization or government.

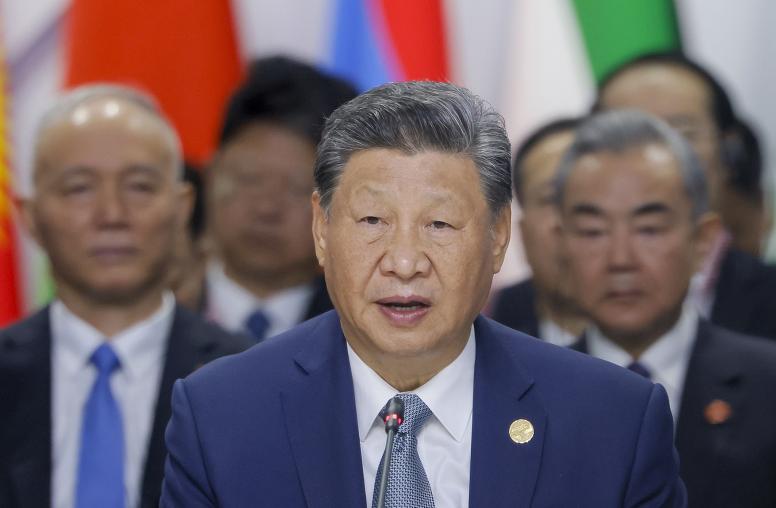

Speaking about “the rise” or the “emerging role” of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) makes little sense these days. The country is no longer simply transforming in a major power, but rather has achieved a level of influence that many other major countries around the world perceive as a threat economically, politically and militarily.

In recent years — in part to deflect and overcome such negative perceptions — Beijing has launched a number of initiatives as a foundation on which China can assume a leading role in addressing a range of global issues.

One of these major initiatives, the Global Security Initiative (GSI), aims to advance alternative, China-friendly approaches to addressing global security problems — with a major focus on shaping principles and norms such as sustainable security, sovereignty, security integrity, commitment to the U.N. Charter, respect for legitimate security concerns, and peaceful dispute settlement.

In Southeast Asia, the Mekong Subregion has become a sort of testing ground for the application of GSI principles, with the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) — a subregional initiative launched by the PRC in 2016 — identified as a “pilot zone” for GSI activities. The LMC initiative enhances economic and diplomatic ties between China and the Mekong countries, thereby enabling China to tailor its cooperation efforts more precisely to the specific requirements of the subregion.

How countries in the Mekong Subregion respond — and whether they respond individually or collectively — to China’s GSI overtures will help shape security along the Mekong River in the years to come. And understanding how Beijing is implementing the GSI in the Mekong Subregion can offer crucial insight into how China might approach other GSI activities throughout Southeast Asia and beyond.

GSI and the Mekong Subregion

The Mekong Subregion, consisting of the countries through which the Mekong River flows —Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam — has been one of the fastest-growing areas in Asia. Yet this subregion confronts many dilemmas on the international scene.

First, each country faces long-standing and deep-seated security challenges both internally and among themselves, including historical animosities, territorial disputes, transboundary environmental problems, and the illicit trafficking of people, drugs and weapons. So, while it may be tempting to view the subregion as a collective entity, each country has different interests in practice.

Second, the subregion lacks a regional institution that can represent them when their collective interests do align. Consequently, the subregion cannot act unanimously to demand or demonstrate regional integrity. This hampers the Mekong Subregion’s ability to confront critical geopolitical dynamics, such as the growing competition between the United States, China and Japan for a leading role in Southeast Asia

China as a Security Provider

Both because of and in spite of these security challenges, the GSI explicitly mentions the Mekong Subregion as an area where China and the world should invest resources to address both traditional and non-traditional security challenges. However, countries in the subregion don’t yet believe China has the full legitimacy to do so.

That is because China itself is a factor in generating many non-traditional security challenges in the Mekong Subregion.

For example, dam construction by Chinese firms on the Mekong River has caused multifaceted environmental and societal problems and challenges. The alterations in water levels caused by dams along the Mekong have resulted in a wide range of biodiversity issues. For people who live along the river, these environmental changes have affected their livelihoods, which depend on fisheries and agriculture. The contentious issues surrounding the management of the Mekong River give rise to inquiries regarding China's ability to assume a prominent role in the subregion, particularly in light of its challenges in effectively engaging in collaborative efforts for regional water governance.

Moreover, the scourge of human trafficking in the subregion means many women from Vietnam, Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos are forcibly sent to China. In addition, Chinese crime syndicates operate large-scale call centers in the subregion to carry out lucrative telephone and online scams, posing a significant challenge in the age of the internet and online shopping, which grew tremendously during the COVID lockdowns.

Given that China has thus far been unable to address its own role in many of the security challenges plaguing the Mekong Subregion, many countries are wary of Beijing’s GSI aspirations and do not necessarily see China as a reliable partner in further security activities.

Responding to the GSI

However, as noted before, the subregion cannot collectively respond to Beijing’s assertions that China can play a larger security role. Unlike ASEAN, which is an international organization that has more bargaining power, there is no entity in the subregion with the authority to speak about subregional interests.

Additionally, the countries in the Mekong Subregion differ in how close they hold their relationship with Beijing. Laos and Cambodia have developed comparatively closer relations with China due to the significant amount of Chinese investment in the countries. Meanwhile, Thailand is still practicing a hedging strategy to extract maximum benefit from relations with both China and the United States. Myanmar is dealing with its own domestic political issues but has developed close ties with China, in part because of shared interests in maintaining their authoritarian forms of governance. Vietnam, on the other hand, holds a more wary opinion of China due to territorial disputes in the South China Sea and other historical animosities.

The dilemma of the Mekong Subregion is finding solutions to tackle security challenges in a way that navigates not just China’s own role, but also the disparate levels of cooperation and interest from Mekong countries.

Looking ahead, for the GSI to succeed in the Mekong Subregion, China needs to first answer two important questions: Number one, what specific policies and programs can China apply to mitigate security problems in the Mekong Subregion, especially those in which China is playing a central role? Second, while China promotes many multilateral platforms and mechanisms that could help bring security and stability to different regions around the world — such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the BRICS grouping and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation — what multilateral mechanism, in which all players have an equal voice, does it have in mind to address the security challenges in the Mekong Subregion?

Although China and the Mekong Subregion have the LMC, which could play an essential role in advancing economic cooperation and building stronger political and security ties between China and the Mekong Subregion, we have not witnessed how China would deal with the non-traditional security issues mentioned above through it.

Therefore, with the unresolved security issues, the Mekong Subregion will seek other options to balance China’s power and to find additional financial, technical and security-related assistance — including from the United States or Japan. Countries along the Mekong will need to skilfully balance the benefits of this diversified approach to their interests with the reinvigorated geopolitical power game emerging in the subregion once again.

Narut Charoensri is an assistant professor in international relations for the School of International Affairs at Chiang Mai University, Thailand.