Despite the domestic turmoil, however, the country’s independent, multidirectional foreign policy remains consistent. Given the consensus-based decision making of the ruling Communist Party, the replacement of top leaders has not affected Vietnam’s outward orientation of maintaining cooperative relations with the United States, China and other key partners.

Diversification in Action

Vietnamese foreign policy follows an established principle of diversification, which was developed as an adaptation to the post-Cold War world. The objective of becoming “friends with all” pre-dates the rise of the current U.S.-China rivalry.

Diplomatically, this strategy has resulted in comprehensive strategic partnerships (CSPs) with seven countries — China (2008), Russia (2012), India (2016), South Korea (2022), the United States, Japan (2023) and most recently Australia (2024) — plus strategic partnerships with at least 15 other countries.

In security policy, Vietnam’s multilateralism is expressed through the “four no’s” of no military alliances, no siding with one country against another, no foreign bases on Vietnamese territory, and no use or threat of force in international relations.

Therefore, contrary to media assumptions, Vietnam’s newer partnerships are “not about containing China” but rather the culmination of a longstanding Vietnamese policy.

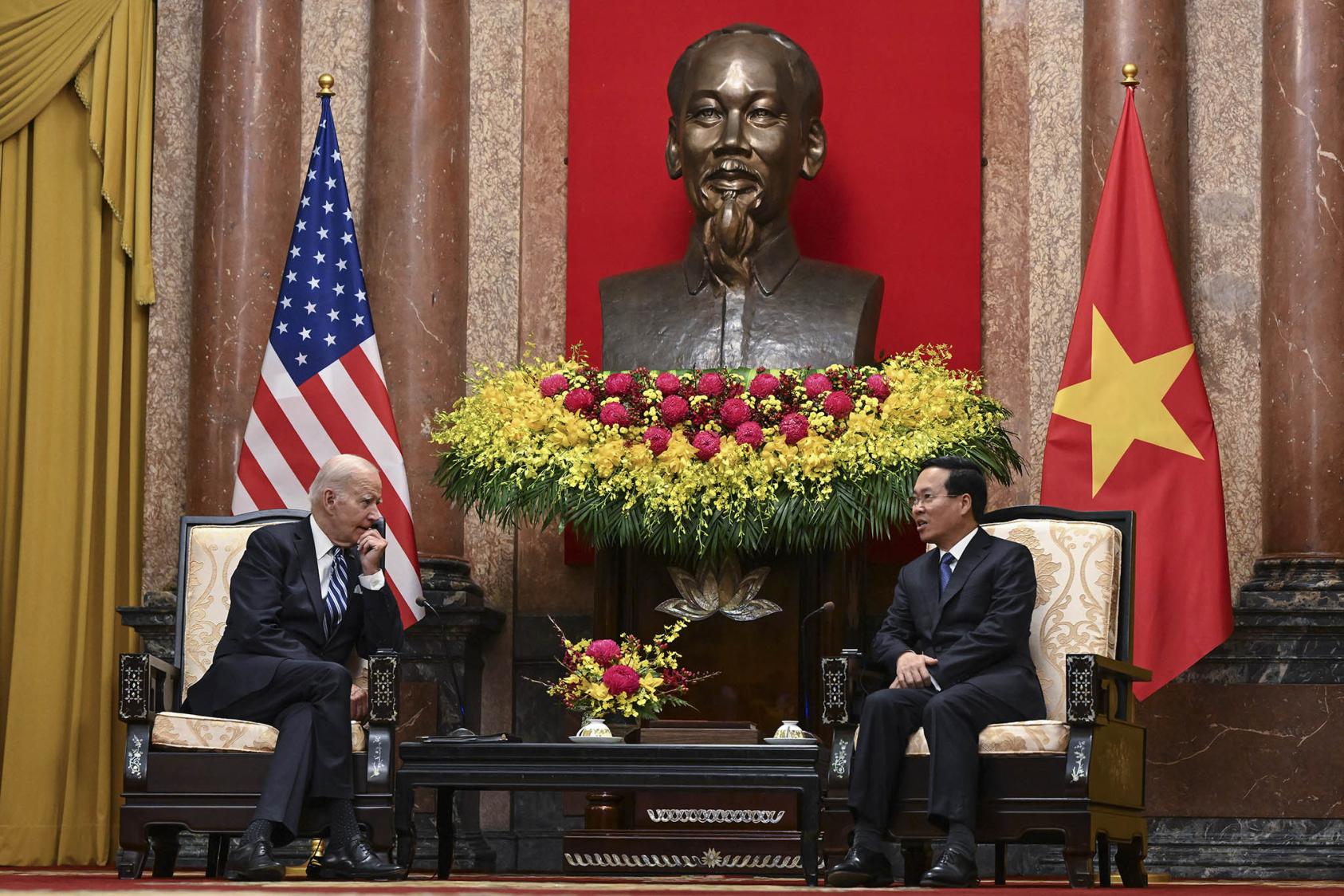

The signing of the U.S.-Vietnam CSP was primarily driven by economic and technological priorities — it was a step forward in bilateral relations, but not a shift toward an alliance with the United States. Similarly, Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s visit to Hanoi in December 2023 strengthened bilateral ties (and adopted China’s desired language of a “community of shared future”) but did not signal a move away from the United States. The sequence and balance of high-level visits and joint statements is choreographed to demonstrate Vietnam’s independence and commitment to multipolarity.

Like all Vietnamese policies, these initiatives have the full backing of Vietnam’s Communist Party. They are not associated with any single leader or faction. CSPs with the United States and its allies are supported by perceived hardliners as well as moderates — suggesting that substantive differences on foreign relations within the Communist Party’s Political Bureau (Politburo) are not significant. If one leader resigns or is replaced, the collective policy remains intact.

The ‘Fiery Furnace’ Purification Campaign

In Vietnam’s single-party political system, the Communist Party Congress meets every five years to select leadership positions and to outline policy directions for the next term, which are then implemented by government ministries and provinces. The 2021 Congress re-appointed Nguyễn Phú Trọng to a third term as the top party leader and elected an 18-member Politburo. Of these senior leaders, one-third have since resigned or been removed following allegations of corruption, in an escalation of the so-called “fiery furnace” campaign that’s been underway since 2016.

Departed officials include former State President Nguyễn Xuân Phúc, Deputy Prime Ministers Phạm Bình Minh and Vũ Đức Đam (the latter not a Politburo member), and former Minister of Industry and Trade Trần Tuấn Anh.

In March 2024, Võ Văn Thưởng, who had succeeded Phúc as president barely a year earlier, was forced to resign following reports of corruption in an earlier provincial position. April saw the departure of the head of the National Assembly, Vương Đình Huệ, followed a month later by Trương Thị Mai, one of only two women on the Politburo. Besides General Secretary Trọng, who will retire after the 2026 Congress, the only remaining Politburo members who have served more than one term (and are thus deemed eligible for top positions) are Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính and newly appointed State President and former Minister of Public Security Tô Lâm.

The scale of high-level personnel changes is unprecedented in Vietnam’s normally stable political system. There is no evidence, however, that foreign policy concerns have played any role in who is investigated. Nor have resignations affected foreign policy outcomes. Notably, the CSPs with the United States, Japan and Australia were negotiated after experienced officials such as Nguyễn Xuân Phúc and Phạm Bình Minh had already been replaced by new leaders without international backgrounds.

Rather, the purges in the Politburo are the inexorable result of the party’s ongoing purification campaign. As the “fiery furnace” moniker suggests, this project aims not just to punish corruption but to remake the party as an ideological force guiding society — a force that, according to party documents, had been weakened and degraded by non-orthodox ideas. Significantly, the identified threats to the party’s authority include not only moral failings but also concepts of pluralism and civil society.

Vietnam’s Shrinking Civic Space

From the beginning of Đổi mới reforms in the 1980s until the mid-2010s, along with economic and social opening, Vietnamese civil society gradually emerged as a vibrant network of registered NGOs, journalists, bloggers and informal community organizations.

Most civil society actors worked in cooperation with the state to deliver public services and improve social policies. Some networks included or were led by former government officials themselves. Civil society groups and their state allies have criticized ineffective policies, such as a series of environmental and land rights cases from around 2008-2016, without opposing the political system as such. While sometimes subject to harassment, surveillance or bureaucratic restrictions, civil society networks were largely tolerated and even encouraged by party and state leaders.

The era of relative openness began to shift with the issuance of Politburo Resolution 04 in 2016, which framed civil society as part of the perceived negative trends of “self-evolution” or “self-transformation” within the party. Even the term “civil society” became suspect.

State approval of NGO projects, previously an administrative obligation, was increasingly hard to obtain. In Cold War-style language, civil society was associated with “hostile and reactionary forces,” or as part of a Western-backed plot, instead of seen as the positive efforts of citizens to contribute to national development. In reality, Vietnamese civil society has never posed any challenge to the Communist Party’s dominance.

Despite the growing restrictions, Vietnamese citizens continued to engage in policy discussions, post on Facebook and advocate for change as part of multi-sectoral networks. A notable success came in 2021, when Prime Minister Chính committed to an ambitious target of carbon neutrality by 2050, adopting many of the recommendations and messages of civil society on climate and energy policy.

However, shortly afterwards, one of the leading campaigners was arrested for “tax evasion,” joining several other leaders of registered NGOs who faced similar charges. Although some of those imprisoned have since been released, due in part to international pressure, arrests of civil society advocates continue to the present. Other NGOs and networks, including those dedicated to transparency and access to information, have closed or ceased most operations. Ironically, the “fiery furnace” has engulfed citizens fighting corruption as well as leaders who benefit from it.

Vietnam is, of course, not alone in experiencing shrinking civic space in recent years — the phenomenon is global. Yet each country has its own political dynamics. Instead of being driven by a populist or charismatic individual, Vietnam’s political system features a collective single-party model that has proven stable and resilient until now. Domestically, the party’s imperative is maintaining its leading role, which is written in the Vietnamese Constitution.

Contradictions and Continuity in Vietnam Foreign Policy

In foreign relations, by contrast, the consensus points toward multiple partnerships, with no relationship leading the others.

The potential for tension between Vietnam’s international partnerships and domestic priorities surfaced in the lead-up to the U.S. CSP with the issuance of Politburo Directive 24, a classified policy aiming to “ensure national security in the context of comprehensive and deep international integration.”

The document instructs party and state agencies to monitor the activities of Vietnamese citizens, including overseas; prevent the formation of opposition groups; and increase restrictions on foreign assistance, especially in the areas of civil society and governance. Like other previous party and public security documents, it conflates peaceful civil society groups with “hostile forces,” in this case with particular attention to independent labor organizing.

Critics such as the human rights organization Project88, who leaked the text of the directive, accuse the party of subterfuge and say they’re attempting to hide domestic repression under the guise of international cooperation. Other observers, seeing nothing new or hidden in the party’s policies, interpret the 2023 directive as “business as usual.” Yet the turnover in leadership and increasing limits on civil society in recent years have been anything but usual.

More likely, Directive 24 and similar statements reflect the growing securitization of Vietnamese policy while attempting to set boundaries between domestic and international arenas. The timing of the directive is expressly linked to foreign relations: It reassures skeptical officials that the new CSPs do not threaten their hold on power. But the policy is directed at an internal audience, not toward China or any other country.

Interpretations of Vietnamese domestic politics within a U.S.-China competitive lens thus miss the mark. Rather than malign Chinese influence, the main concerns for the United States should be maintaining protection of human rights as one of the pillars of the CSP and limiting effects of political turmoil on foreign assistance programs, investor confidence and people-to-people exchanges. In this way, Vietnam’s international integration can proceed alongside contested questions of political succession and state-society relations.

PHOTO: President Joe Biden meets with President Vo Van Thuong of Vietnam in Hanoi. September 11, 2023. (Kenny Holston/The New York Times)

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s).