Morocco: Betting on a Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Morocco's truth and reconciliation commission—the first in the Arab world—provides a road map to further democratization and a positive model for social and political reforms in the rest of the Arab world.

Summary

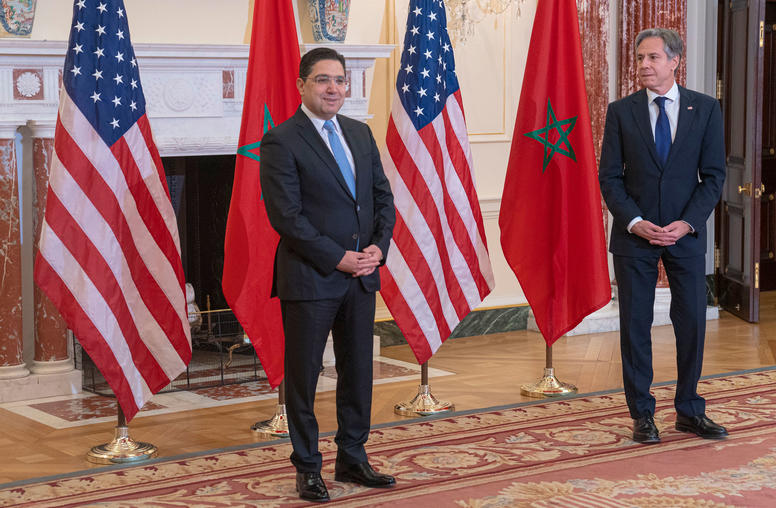

- Facing the Atlantic and Mediterranean, just nine miles from the Spanish coast, Morocco is essential for stability in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and American interests in these regions. The United States and the European Union fully recognize its strategic importance. Its proximity, large diaspora, and extensive trade with Europe place it at the top of the EU's Mediterranean strategy agenda. The United States has designated Morocco a major non-NATO ally; it also was one of the first Arab countries to sign a free-trade agreement with the United States.

- The Kingdom of Morocco is facing four challenges: weak economic growth; a social crisis resulting from social inequalities, with 20 percent of the population in absolute poverty and 57 percent illiterate; lack of trust in the governing institutions because of the high level of corruption; and an unstable regional and international environment. These factors strengthen the appeal of various Islamist movements, from moderate to more radical groups such as the authors of the deadly bombings in Casablanca in 2003 and Madrid in 2004. Moreover, the conflict over the Western Sahara places Morocco's and Algeria's armies, the two most powerful in North Africa, toe to toe.

- Unlike Tunisia and Algeria, since the end of the Cold War Morocco has taken steps toward political liberalization, and its pace has accelerated since Mohammed VI came to the throne in 1999. As part of the process of liberalization, the king established a truth and reconciliation commission (TRC) in January 2004. This is one of very few cases in which a TRC was created without a regime change. Thousands of victims tortured during the reign of King Mohammed's father, King Hassan II, have been given the opportunity to voice their sufferings publicly and have been promised financial compensation. Such outcomes are unprecedented in a region known for its culture of impunity.

- Morocco is the first Arab Islamic society to establish a TRC. Its experience shows that political factors play a primary role in the functioning of such a body, while religious and cultural factors are of secondary importance. Although the Moroccan TRC is not an exportable model, it could inspire other majority Muslim societies, such as Afghanistan and Lebanon, which are envisaging or might set up TRCs to confront crimes of past regimes.

- Some security experts hoped the TRC would be effective in the "soft war" against terrorism by winning the hearts and minds of the population. The actual experience in Morocco shows the limits of this approach. The tension is too strong between the perceived requirements of the antiterrorist struggle and a process to establish accountability for past crimes and advance democratization. In the final analysis, the "war against terrorism" has limited the TRC's impact in Morocco.

- The report of the Moroccan TRC, published in early 2006, recommended diminution of executive powers, strengthening of parliament, and real independence for the judicial branch. The king and the political parties must decide in the coming years if they will permit the transformation of the "executive monarchy" of Morocco into a parliamentary monarchy. This decision will affect the stability of the kingdom, North Africa, and, to a lesser extent, Europe and the Middle East.

Introduction

After forty-four years as a French protectorate, Morocco gained its independence in 1956 under King Mohammed V. In 1961 Hassan II succeeded to the throne and ruled until his death in 1999. He was the main architect of the "executive monarchy" that still rules Morocco today. Under the constitution promulgated by Hassan II in 1962, the king has nearly unlimited powers. Article Twenty-three of the constitution states, "The king is inviolable and sacred." He holds sole executive power. He appoints and fires the prime minister. He can suspend the constitution or dissolve the assemblies and is chief of the armed forces. As Commander of the Faithful (as Hassan II styled himself in the constitution), he exercises spiritual power over Moroccan Muslims.

Recommendations

- Reform the system of governance. Although it initially made the security apparatus nervous, the platform of reforms advocated by the IER will contribute to strengthening the democratic option, the most conducive to long-term stability. Likewise, as the IER suggested, a public apology by the prime minister or the king to victims of past abuses and the nation would constitute official recognition that the violations were the product of an organized, structural, hierarchical system that reached all the way to the pinnacle of the state.

- Lustration. Even if the Moroccan authorities remain determined not to punish judicially those responsible for repression during the Years of the Iron Fist, they nevertheless could drive those responsible from public office. This measure would strengthen the credibility of the state. If state organs cooperated in revealing the circumstances and fate of the "disappeared," their credibility also would be enhanced. Without their help, the IER has proven to be incapable of accomplishing this objective.

- Providing technical support. Western governments could help the Moroccan government reform its judicial system and offer technical support in training police forces, judges, and prosecutors, thus reinforcing respect for human rights.

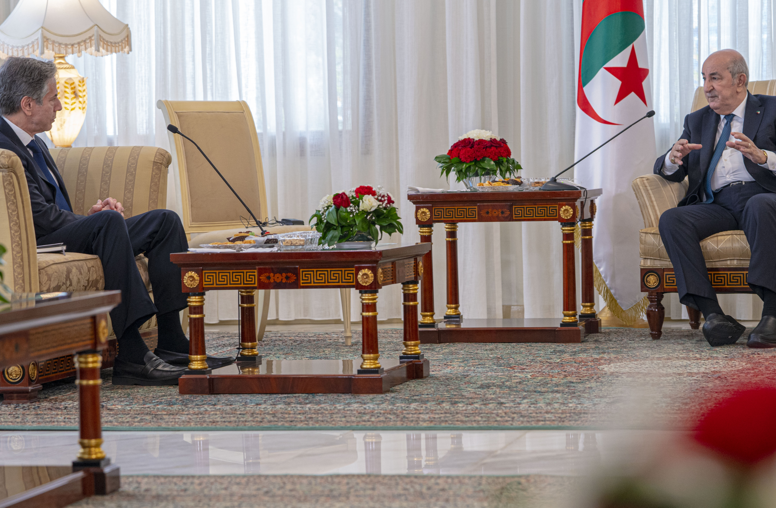

- Resolving the situation in the Western Sahara. In coordination with its European allies, the United States would be well advised to start a diplomatic initiative to help settle the Western Sahara conflict, which has lasted since 1975. This conflict remains the principal barrier to normalization of relations between the two most important countries in North Africa, Morocco and Algeria, both of which play a key role in the stability of this strategic region.

About the Report

This report is part of an ongoing study of the mechanisms of transitional justice. Based on extensive data and interviews in 2005-06 with ordinary citizens, victims who both testified and refused to testify, commissioners, high-ranking bureaucrats, political leaders, and Moroccan and international NGOs, it explores the potential and limits of the first truth and reconciliation commission (TRC) in the Arab world. It demonstrates the difficulties of a TRC when society is caught up in a struggle between Islamic extremists and repressive security organs of the state. Despite its limitations, the Moroccan TRC provides a road map to further democratization. It also provides a positive model for social and political reforms in the rest of the Arab world and encourages local and international players to support such reforms, which could contribute to stability in Northern Africa and security in Western Europe.

Pierre Hazan is a senior fellow at the United States Institute of Peace. Formerly the UN correspondent in Geneva for the French newspaper Liberation and the Swiss daily Le Temps, he has covered several international crises, including those in the Balkans, Afghanistan, the African Great Lakes region, Somalia, and the Sudan. He has previously written Justice in a Time of War: The True Story behind the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (2004) and The Victim's Guide to the International Criminal Court (2003). He has also produced numerous television documentaries concerning international criminal justice.