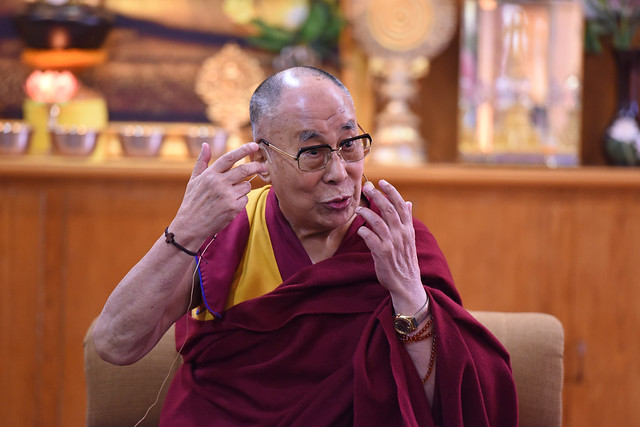

In a conference room at his offices in northern India, the Dalai Lama sat among young civil society leaders trying to build peace in their homelands scarred by violent conflicts. These days, a question troubles him when he wakes from a night’s sleep. “During that eight, nine hours, how many people [have been] killed in different parts of the world?” he asked. “And how many children died due to starvation?”

In this slideshow, USIP photographer Bill Fitz-Patrick captures this month’s two-day meeting between the Dalai Lama and youth leaders struggling to build peace in homelands facing violent conflicts. Fitz-Patrick, a longtime White House photographer to four U.S. presidents, comments on the photos in the story—and in the full version of the slideshow, below.

The Dalai Lama sat stone-faced, thinking. His question hung like the sound of a tolling bell. “The room was dead silent. It’s a cliché, but you could have heard a pin drop,” said Bill Fitz-Patrick, who was covering the meetings as USIP’s staff photographer.

For two days this month, the Tibetan Buddhist spiritual leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate mentored the group of 25 youth leaders gathered by USIP. Fitz-Patrick watched and listened as he shot the photos above. He is a witness to a half-century of war and peacemaking, from Army tours in Vietnam and Berlin to 15 years as a White House photographer to four U.S. presidents.

“Not long after coming home from Vietnam, I was working in a camera store in Washington, and I wound up getting hired to the White House photo staff under President Nixon,” Fitz-Patrick said. “I worked under Presidents Ford, Carter and Reagan. People had respect for these leaders partly because they had real, practical power. An American president can pick up the phone and give a directive that can change something. The Dalai Lama is a Buddhist monk who lives in exile. People respect him not for any practical power that he has, but for his spiritual power—the way that he touches people’s hearts and conscience.”

The Dalai Lama said he monitors global violence, from the assaults on Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar to the wars in the Middle East and Africa. On BBC and CNN, “I see too much … suffering. Sometimes I cry.”

‘Our Hope … Is on You’

At age 82, “since last year, I am feeling more tiredness,” he said, and must restrict his travel and rely on others for the peacebuilding work he hopes to see achieved in the last years of his life. “Now, you young people, all of our hope and trust is on you,” he told the group.”

For two days, the Dalai Lama heard stories from the youth leaders—of being forced from home by warfare, or being arrested or beaten by authoritarian police forces. Others recounted government or traditional authorities telling them they were too young, or were ineligible as females, to have their voices heard in their communities.

The Dalai Lama, who saw his own homeland invaded as a child before being forced to flee into exile, empathized. “Now the question,” he said, is “should we remain demoralized” in the face of violence and suffering? “Who created these problems? We human beings, ourselves! So then logically, if we make some effort, with vision, certainly we can reduce the suffering that we human beings created.”

For Fitz-Patrick, watching the exchanges through his camera lens, “it was remarkable to see how the Dalai Lama makes connections with people, immediately and intensely,” he said. They were “so fully engaged by him,” said Fitz-Patrick. “When I was framing him up through the lens, I was, too.”

USIP photographer Bill Fitz-Patrick took these photos of the two days of meetings between His Holiness the Dalai Lama and USIP’s delegation of youth leaders from around the world. “It was remarkable to see how the Dalai Lama makes connections with people, immediately and intensely,” said Fitz-Patrick. During the sessions, the Dalai Lama met briefly with many of the leaders individually—here with Tin, who promotes human rights and development in Myanmar.

“This is Lourd, who comes from the Iraq’s Kurdistan region. Like the others, she was so fully engaged by him,” said Fitz-Patrick. “When I was framing him up through the lens, I was, too.” Lourd co-founded a non-government organization in Iraq that builds peace by bringing together people of different religious, ethnic, and political backgrounds.

Darine is a young Sudanese physician working with communities of people displaced by warfare in her country, including girls and women subjected to violence. Bill Fitz-Patrick recalled shooting this photo: “They spoke for a few moments, and then, as they connected emotionally, this happened. It was reverential.”

From South Sudan, Ger Duany grew up during the Sudanese civil war. He was taken by the military and forced to fight as a child soldier until he escaped, walking hundreds of miles to become a refugee. Duany since has become a film actor and fashion model, and works with the U.N. refugee agency, UNHCR, to promote understanding of the problems facing millions of displaced people worldwide. In workshops with the young civic leaders, Duany discussed the ways that victims of war can turn traumatic experiences into personal growth. “During a break in the meetings, Duany came and knelt beside the Dalai Lama’s chair to talk one-on-one,” Fitz-Patrick said.

Jeremy Richman is an American specialist in neuroscience and pharmacology. He is the co-founder of the Avielle Foundation, which works to prevent violence and build compassion, and is named for Richman’s six-year-old daughter, who was killed in the 2012 mass shooting at a school in Newtown, Connecticut. Early in the group’s sessions with the Dalai Lama, the two spoke one-on-one.

The young leaders asked questions and explained problems they were facing. The Dalai Lama offered advice and empathy. Here Fatima, a women’s development activist from Nigeria, asks a question. At home, she leads a mentoring program for Nigerian girls, including rescued victims of the Boko Haram extremist group.

“Look at their faces—how fully and happily they’re engaged by him,” said Fitz-Patrick. “These gatherings around him would happen each time we took a tea break. The group sessions each ran for several hours, and he would be speaking, and maybe in the middle of a sentence, suddenly, he would say, “Time for tea!” And his assistants would have prepared tea and cookies in the back of the room. And they would bring him his tea in his green mug. And he would start an informal conversation with one or two people, and pretty quickly, a group like this would gather.”

“One of the youth leaders was Nagi, who has led peace movements in Sudan,” said Fitz-Patrick. “Here, His Holiness pointed at Nagi’s shaven head and told him, ‘you could be a Buddhist monk!’”

During a tea break, the Dalai Lama talks with Adeng, a journalist and human rights from South Sudan, and examines how her hair is braided. “We are the same, human beings,” the Dalai Lama told the group. “Different hairstyle, different color, different shape of nose, but basically, the same human beings.”

The Dalai Lama and USIP President Nancy Lindborg co-led discussion sessions with the group of youth leaders. The Dalai Lama is known for his ready, mischievous sense of humor—and laughter was frequent in the room.

Height can be an advantage for a photographer who has to shoot amid crowds of people. USIP’s staff photographer, Bill Fitz-Patrick, is six feet, six inches tall—and His Holiness has commented on Fitz-Patrick’s size each time they have met. “I wish I could remember what I told him here that got such a big laugh from everyone,” Fitz-Patrick said.

“To get just the picture you want of someone in a conversation, you have to anticipate a gesture or a facial expression, so that you’re squeezing the shutter almost before you see it.” Fitz-Patrick said. “So as I’m framing him, I’m listening to his voice, trying to sense when he’s about to make a movement that I’ll want to capture.”

“Here is the full group gathered around His Holiness,” said Fitz-Patrick. “Bright lights bother his eyes, so the room actually was dimly lit, and it would have been disruptive to use a flash. So I set the camera’s ISO up to 2500, which was pushing the limit for getting good pictures without them getting grainy.”