The ‘Russia Factor’ in NATO-Japan Relations

The war in Ukraine shifted Japan’s stance toward Russia. But will that lead to deeper long-term engagement with NATO?

Russia’s illegal and unprovoked aggression against Ukraine has changed Japan’s assessment of Russia, as well as Tokyo’s policy toward Moscow. In doing so, it has also brought NATO and Japan closer together in their views of Russia and led to broader NATO-Japan engagement. Whereas Russia was once a complicating factor in the NATO-Japan relationship, it is now a factor promoting relations.

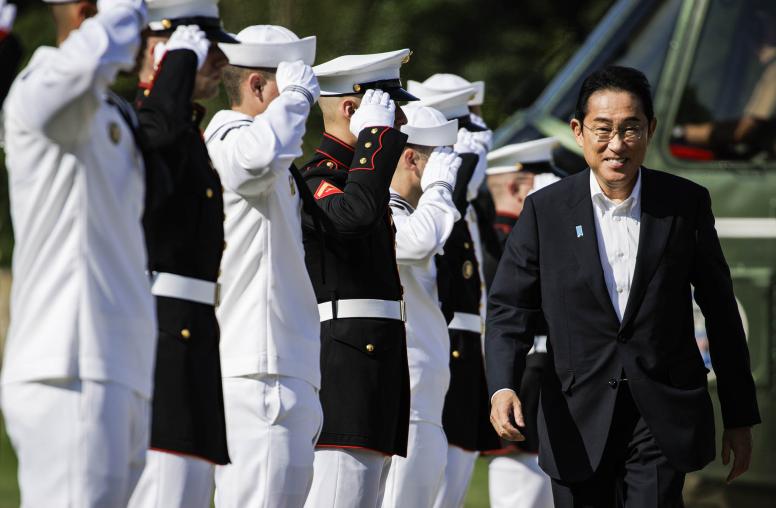

As Prime Minister Fumio Kishida prepares to join NATO leaders at the alliance’s July summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, a look at the “Russia factor” in NATO-Japan relations will help put the current state of the relationship into broader context.

Russia and NATO in Japan’s Foreign Policy Until 2022

Russia has not been a true friend of Japan since World War II. While the two countries re-established diplomatic relations in 1956, which allowed the war to end officially and Japan to join the United Nations, they have yet to conclude a peace treaty because of territorial disputes over islands northeast of Hokkaido known as the Northern Territories in Japan and the Southern Kuril Islands in Russia.

When the West embraced the newly democratized Russia in the 1990s, Japan remained hesitant and was the least enthusiastic country among the Group of Seven (G7) partners when Russia joined the framework in 1998, making it the G8.

Yet, under the premiership of Shinzo Abe, Tokyo became committed to improving relations with Moscow in the hope of solving the territorial disputes (i.e., getting some islands returned from Russia). Abe’s overtures to Russia did not end after Russia’s illegal and unilateral annexation of Crimea in March 2014, making Japan arguably — and somewhat ironically — the least-willing country when the G7 subsequently decided to evict Russia. Japan imposed only a nominal set of sanctions on Russia in a bid to keep the window of opportunity open for progress in the peace treaty negotiations.

In addition to addressing the territorial disputes, the Abe government also argued that improving relations with Russia was important amid the rise of China in Northeast Asia’s strategic landscape. Tokyo wanted to use Moscow as leverage vis-à-vis Beijing, or at least try to prevent Russia and China from forging a united front against Japan based on historical, territorial and other issues. Tokyo’s efforts to improve relations with Moscow were, in essence, part of its China policy.

However, in hindsight, it was almost an illusion to think of using Russia as a bargaining tool against China. For Russia, it’s an undeniable fact that China is far more important and consequential than Japan — making it difficult to assume that Russia would be prepared to sacrifice its relations with China for the sake of improving relations with Japan. Abe’s rather optimistic views were partly based on the observation that Russia’s behaviors in Asia were more peaceful and benign than its actions in Syria or Ukraine.

Given Japan’s position on Russia during the Abe era, Japan and NATO did not see eye-to-eye regarding Moscow. Some NATO countries, most notably the United States during the Obama administration, were suspicious of Japan’s Russia policy in the mid-2010s. The Obama administration tried to prevent Abe from inviting Putin to Japan — a meeting that eventually materialized in President Obama’s final days in office in December 2016. Additionally, whereas NATO showed interest in missile defense cooperation with Japan, Tokyo was cautious because it did not want to provoke Russia, which was vehemently opposed to the U.S.-led missile defense system in Europe.

Put simply, Russia was not a factor fostering NATO-Japan relations, but a factor complicating or even hindering the relationship — something called the “Russia gap” existed. NATO-Japan relations in the 2000s and 2010s instead developed in the context of cooperation in Afghanistan. Though Japan sent no troops there, the two cooperated in the civilian domain, including on provincial reconstruction teams, while the alliance was commanding the International Security Assistance Force.

Japan’s Response to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was shocking to Japan. The attack was in blatant violation of international law, and the scale of the devastation and sacrifice of Ukrainian soil and people was beyond imagination.

Up until the start of the invasion, Tokyo was still somewhat cautious in taking a hard line against Russia. But the start of the war changed the situation and the Kishida government decided to take a tough position, including by imposing sanctions on Russia. Kishida repeatedly emphasized the importance of keeping aligned with other G7 partners.

There are three major reasons why Tokyo has taken a tough position on Russia, representing a clear departure from what it did back in 2014. First, the scale of Russia’s actions is different this time, making it simply impossible to be indifferent.

Second, Prime Minister Kishida sees the invasion as something presenting a direct challenge to Japan, repeatedly arguing that “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow.” This sense of urgency, which was still nonexistent in 2014, has been stimulated by the further rise of China and the increasing strategic cooperation between Russia and China. Opposing any change of the status quo by force anywhere in the world is now firmly established as the central discourse of the Kishida government, given that Beijing is closely following the war in Ukraine and the response of the international community.

Third, Kishida was not as personally committed as Abe to the idea of improving relations and concluding a peace treaty with Russia.

Japan’s assistance to Ukraine has largely been civilian in nature because of the country’s self-imposed restrictions on arms export. However, the Kishida government provided a limited amount of non-lethal equipment like transport vehicles, bulletproof vests, helmets and medical equipment from the stocks of the country’s Self-Defense Forces. The total volume of aid committed, including financial assistance, reached $7.1 billion as of March 2023, making Japan one of the biggest contributors to Ukraine.

Japan’s support to Ukraine has an important NATO dimension as well. Japanese representatives have been participating in the NATO-led Ukraine Defense Contact Group meetings despite providing no lethal weapons to Ukraine. Furthermore, Japan has provided $30 million to NATO’s trust fund for Ukraine, channeling non-lethal equipment and materials to the Ukrainian military.

At the political level, Prime Minister Kishida attended the NATO summit in Madrid in June 2022 and Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi attended the NATO foreign ministers’ meetings in April 2022 and April 2023, with all three meetings putting a spotlight on the war in Ukraine.

While it’s true that both Kishida and Hayashi used those occasions to raise issues related to the security environment in East Asia, particularly on China and North Korea, it is simultaneously important that Tokyo is now more exposed on a regular basis to transatlantic conversations about Russia and Ukraine.

Japan and the other “IP4” countries — Australia, South Korea and New Zealand — are again invited to the NATO summit in Vilnius this July, making the presence of Indo-Pacific representatives at NATO meetings a now-regular feature. NATO thus demonstrates that it is capable of maintaining interest and engagement in the Indo-Pacific region amid the war in Ukraine in its own neighborhood.

It was in this context that NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg visited Tokyo in January and February 2023. His and his predecessors’ previous visits to Japan were largely seen as part of diplomatic outreach activities, separate from the core business of the alliance. This time the atmosphere was different. During his stays in both Seoul and then Tokyo, Stoltenberg passionately talked about the threat of Russia and concerns over the increasing strategic cooperation and alignment between Russia and China. In Seoul, he directly “urged” South Korea to send weapons to Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine has thus resulted in closer strategic alignment and more frequent interactions at all levels between NATO and Japan. Furthermore, putting aside the EU, Japan is the only G7 member that is not part of NATO. Therefore, it is not surprising that the G7, of which Japan holds the presidency this year, often acts as a bridge for Japan and NATO. The fact that the extraordinary G7 summit in March 2022 took place at NATO headquarters in Brussels on the margins of an emergency NATO summit on Ukraine is a good case in point.

In Light of Ukraine, What Comes Next?

As noted, Prime Minister Kishida has repeatedly argued that “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow.” This sort of awareness is reflected in Japan’s National Security Strategy (NSS), adopted in December 2022. The document warns that:

Japan’s security environment is as severe and complex as it has ever been since the end of World War II. Russia's aggression against Ukraine has easily breached the very foundation of the rules that shape the international order. The possibility cannot be precluded that a similar serious situation may arise in the future in the Indo-Pacific region, especially in East Asia.

Tokyo clearly sees the connectedness between the security of East Asia and that of Europe. This explains why Japan is imposing an unprecedented level of sanctions on Russia this time compared to the annexation of Crimea back in 2014. Although strengthening the alliance with the United States remains a top priority, Tokyo is reinforcing its efforts to develop more security partnerships, including in Europe, in light of the increasing connectedness between Asia and Europe. The concept of Europe and NATO as a strategic partner has therefore been “mainstreamed” in Japan’s foreign and security policy.

The war in Ukraine has also influenced Japan’s domestic debates on security and defense. First, more and more people are now talking about security and defense on a daily basis, including about what it takes to defend the country, something ordinary people in Japan had not asked for many decades. Stimulated by Russia’s invasion and the heightened tensions over the Taiwan Strait — as well as North Korea’s ever more frequent ballistic missile launches, some of which have flown over Japan — there is now stronger public support for the idea of strengthening the country’s defense posture, including the defense budget. In adopting the NSS, the Kishida government committed itself to spend 2 percent of GDP on defense by FY 2027, a long-time NATO target.

One of the biggest lessons that Japan has drawn from the war in Ukraine is the importance of deterrence. While Ukraine’s brave resistance against Russia is laudable, it would have been far better if Ukraine were able to prevent Russia from invading the country in the first place. The fact that Russia has nuclear weapons makes things more difficult, because there are always fears that Russia might use them — which forces NATO countries to tread cautiously to avoid unintended escalation of the conflict.

The inconvenient news for Japan and other U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific region is that the same logic could be applied to China, another nuclear state. In generic terms, it is the challenge of addressing a nuclear-armed adversary that seeks to change the status quo by force. If NATO and the United States could not effectively address this challenge vis-à-vis Russia, how likely is it that the United States would be able to address a similar — albeit much bigger — challenge from China in the future?

That said, another far more benign lesson from the war in Ukraine is the fact that NATO has been successful in deterring Russia from attacking or militarily provoking NATO allies. The Biden administration, while precluding the idea of sending American troops to Ukraine, has demonstrated a strong commitment to defend “every inch” of allied territory from the beginning.

In short, NATO’s deterrence seems to be working. Assuming that this is the main lesson to be drawn from the war, Kishida’s warning of “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow” could be taken as “Poland today may be Japan tomorrow.” Yet, it remains to be seen to what extent Tokyo is prepared — politically and legally — to play a similar role on Taiwan to what Warsaw is currently playing vis-à-vis Ukraine. After all, Japan is a country that has only slowly awakened to the worsening realities of military competition in the region.

There is still no end in sight for the war in Ukraine, and Japan and NATO will need to cooperate more in supporting Ukraine and deterring Russia. At the same time, the China-Russia dimension of the war in Ukraine — and the challenges posed by the rise of China itself — will loom large for Japan and NATO in the coming months and years. The extent to which the two could address China together would determine the true depth of the relationship after addressing the war in Ukraine. The NATO summit in Vilnius may provide an interesting preview of how the parties see these questions evolving.

Dr. Michito Tsuruoka is an associate professor at Keio University and currently a visiting fellow at the Australian National University.