What to Know About Gabon’s Coup

While the situation remains tenuous, the military takeover represents the latest in a long line of coups across Africa.

On August 30, just hours after Gabon’s election commission announced that President Ali Bongo Ondimba had been elected to a third term, a group of Gabonese military officers from the elite presidential guard unit seized power and placed the president under arrest at his palace. Later that day, the officers declared General Brice Oligui Nguema as chairman of the transition. While the election itself had been marred by reports of irregularities, the officers’ coup marks the latest in a long line of recent military takeovers across the African continent that have jeopardized regional stability and security.

The situation remains tenuous, but it appears that the officers are consolidating their control over the country. If they do wrest full control away from President Ali Bongo, they will end more than five decades of his family’s dynastic rule in Gabon. But what the coup leaders intend to do once they’ve cemented themselves in power remains unclear, with unspecified plans for a transition circulating amid international condemnations and demands for a return to civilian rule.

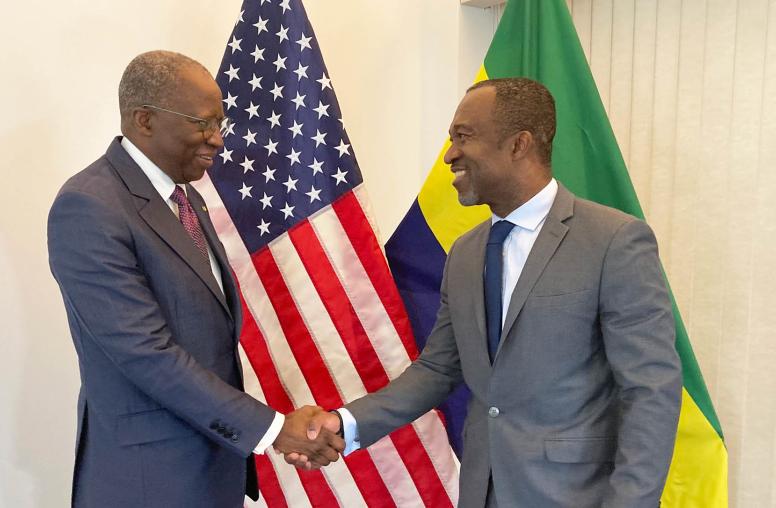

USIP’s Elizabeth Murray and Archibald Henry look at the latest developments from Gabon, how the coup fits into the broader trend of military takeovers in Africa, and what leverage regional forums and the international community might have to press for a short transition back to democratic governance.

Who is behind the coup attempt and where does the situation stand at the moment?

Murray: The military officers who carried out the coup have established what they call the Committee for the Transition and Restoration of Institutions (CTRI). In a video address shortly afterward, the military officers also cancelled the election results, suspended all government institutions and closed the country’s borders. General Brice Oligui Nguema, the leader of the group, was then announced as the new leader of the country’s transition. Nguema has headed Gabon's Republican Guard, an elite force responsible for protecting the president and other senior figures, since 2019.

Gunfire was heard near the palace shortly after the announcement, and the president appeared in a video later in the day asking his supporters to “make noise.” The country, including the capital Libreville, appears calm at the moment, with the military junta consolidating their control and some citizens expressing support for the coup. The military has announced a curfew and has reinstated foreign media outlets that were banned by President Bongo’s government during the recent election.

If the officers succeed in seizing power, they will have ended 55 years of dynastic rule under the Bongo family. President Ali Bongo Ondimba’s father, Omar Bongo, ruled Gabon from 1967 until his death in 2009, with Ali Bongo elected to succeed his father the same year.

That 2009 election, Ali Bongo’s re-election in 2016 and his most recent re-election this month were all marred by significant irregularities. In the most recent election, major opposition parties united behind a single opposition candidate, former Education Minister Albert Ondo Ossa, who officially won 31 percent of the vote. Opposition parties sharply criticized the government for modifying the electoral rules in the month prior to the election and limiting the free flow of information by cutting major internet service providers in the days around it.

Although Gabonese citizens express strong support for democracy, a large majority of them do not believe that elections allow voters to remove leaders who do not meet their expectations. In addition to their frustrations over unfair elections and dynastic rule, citizens of Gabon experience widespread poverty despite the country’s significant natural resources in timber, oil and manganese that give Gabon the second highest per-capita GDP in mainland sub-Saharan Africa.

The leaders of the coup may be able to capitalize on citizens’ frustration to garner support for the coup, if it indeed holds. Since the president and his inner circle have historically enriched themselves through their access to power, however, it is likely that the military junta will continue to do the same at the expense of ordinary citizens.

What has been the early international response, and what reaction might we see from regional forums such as the African Union compared to the recent coup in Niger?

Henry: African Union (AU) Commission President Moussa Faki immediately condemned the coup attempt as a violation of AU norms on elections, democracy and governance. The AU urged all parties in the country to facilitate a peaceful return to constitutional order and called on Gabon’s military to guarantee the safety of President Ali Bongo.

China also called for peaceful dialogue and guaranteeing the security of President Ali Bongo, while Russia expressed concern and called for a stabilization of the situation. The United States, the European Union and France — a longstanding strategic ally and former colonial power of Gabon — specifically condemned the coup, and Nigerian President Bola Tinubu noted deep concern at an “autocratic contagion” spreading across the continent.

One of the big question marks revolves around the response of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). The regional forum is headquartered in Gabon’s capital Libreville and currently enjoys significant political and financial support from the country, which is one of ECCAS’ main contributors.

Considering this relationship, it is unclear whether ECCAS would have strong leverage in pressing for a return to civilian rule, but the organization may be poised to play an important role in dialogue pending the results of the coup.

In response to a wave of coups across the Sahel, to Gabon’s north, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has imposed sanctions on various military juntas and even called for the deployment of a military force in Niger to enforce a return to constitutional order. However, the ECOWAS response to coups has been largely inconsistent, hampered notably by mixed messaging on the latest coup in Niger and ineffective sanctions, jeopardizing the credibility of the organization in the eyes of local populations. Overall, the AU and sub-regional bodies like ECOWAS have been unable to make meaningful progress on a return to civilian rule in Sahelian countries.

That’s why the response of the AU and ECCAS, in particular, will be important to watch in the coming days — as well as whether a regional or international mediation will be needed to facilitate dialogue and support a return to civilian rule and constitutional order.

How is the Gabon coup different or similar to other coups in Africa that have happened recently, and how does it fit into the trajectory of that trend?

Henry: While military takeovers or coup attempts have become increasingly common in Africa over the last few years, the August 30 coup in Gabon is distinct from the recent coups in the Sahel region in a few ways. In Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, coup plotters stated the need to guarantee security from jihadist threats and called for independence vis-à-vis former colonial power France — enjoying popular support as a result. Coups in the Sahel have been followed by military junta’s stark distancing from Paris and rapprochement toward the Kremlin and the paramilitary Wagner Group.

In contrast with countries in the Sahel, Gabon has enjoyed relative stability in recent years. It has also maintained close ties and strategic relationships with France, China and the United States.

Rather, the coup in Gabon occurred in the middle of an electoral cycle that featured accusations of fraud by the opposition and government restrictions on the internet and independent news broadcasts. More broadly, Gabon has experienced frustrations over authoritarian rule — characterized by resource capture and predation by elites, deep structural inequalities despite the country’s wealth, and weak democratic institutions.

In this regard, Gabon’s coup resembles more closely the 2021 coup in Guinea that followed the controversial re-election of President Alpha Conde in 2020, or even the 2015 coup attempt in Burundi that was precipitated by urban protests over then-President Pierre Nkurunziza’s re-election bid for a third term.

Beyond Gabon, other former French colonies are at risk of instability, with similar institutional conditions found across countries in Central Africa as well as often turbulent electoral cycles or political transitions. Combined with the politicization of the military and increasingly outspoken public sentiment against ruling elites, the Central Africa region faces a range of vulnerabilities to further coups.

The recent wave of coups in West Africa has no doubt contributed to the normalization of military takeovers, which could embolden other leaders to seize power by force amid electoral disputes. The reliance on the rule of force rather than rule of law poses grave risk for the sanctity of electoral processes and the future of democratic civilian rule and governance across the continent.

Still, each coup is different, and it’s important to recognize the unique vulnerabilities of each context and adopt a tailored approach. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to preventing, addressing and responding to coups — whether in Africa or beyond. Categorizing coups in Africa as a uniform, inevitable trajectory could be misleading and unhelpful for informed analysis and response.

Does the U.S. and international community have any leverage to press for a return to civilian government, whether as part of a transitional process or a restoration of the election results?

Murray: The United States and other international allies will be well-served to engage with all parties in Gabon as the situation becomes clearer in the coming days. The United States has expressed deep concern about the military officers’ seizure of power through a statement from White House national security spokesperson John Kirby. At the same time, U.S. and international policymakers had expressed concern around irregularities in the recent elections, including the refusal to allow international observers.

While the United States and international community have limited leverage to push the military officers to return power to civilians, international partners should use diplomacy, incentives and disincentives to push for a transitional period that is short and transparent. The international community must also prioritize support for the reform of Gabon’s government institutions, which are weak and historically have served primarily the elite.

If the coup succeeds and a transition occurs, the international community should actively engage not just the military officers and President Ali Bongo and his inner circle, but also opposition political parties, religious leaders, and other civil society figures. For the Gabonese to establish a well-functioning democracy, they will need support in bolstering independent media and creating opportunities for all sectors of Gabonese society — including those outside the traditional elite — to engage in dialogue about the future of their country.

Over the longer term, the U.S. approach to the region should include sharpening our analysis on coup risks and helping democratically elected leaders demonstrate to their citizens the tangible benefits of democratic rule.

Archibald Henry is a program officer for Central Africa and the Sahel at USIP.