Two Years Later, What Has the Indo-Pacific Strategy Achieved?

The Biden administration’s strategy underscores the importance of deep and consistent U.S. engagement for advancing U.S. national interests.

This month marks the second anniversary of the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS). USIP experts Carla Freeman, Mirna Galic, Daniel Markey, and Vikram Singh assess what the strategy has accomplished in the past two years, how it has navigated global shocks and its impact on partnerships in the region.

Two years since the launch of the Indo-Pacific Strategy, what have been the most tangible takeaways for the United States and countries in the region?

Singh: A key takeaway for U.S. leaders is that deep and consistent U.S. engagement in the Indo-Pacific is invaluable to U.S. national interests. The IPS framed a strategic vision for an Indo-Pacific that is free and open, connected, prosperous, secure and resilient. The idea of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” — a concept created by the late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in a speech to the Indian Parliament in 2007 — leads the strategy because it combines the dreams of the people of the region with the interests of the United States and its democratic allies. And it sets the United States and its partners’ vision for the region apart from China’s.

As Beijing became the main trading partner and source of investment and infrastructure for countries throughout the region over the past 20 years, it also became central to connectivity and trade. And for the price of acquiescing to China’s regional and global ambitions, Beijing would help Indo-Pacific nations be more secure in a narrow tactical sense, for example by selling surveillance technology and defense equipment. But building a free and open Indo-Pacific, as the IPS envisions — with democratic institutions, free media, transparent governance and shared standards for the commons ranging from the ocean floor to space, cyberspace and new technologies — can only be achieved with support from the United States and its democratic partners like Australia, India and Japan.

In implementing the IPS, Washington found vast interest in and appetite for new and upgraded partnerships and initiatives. This includes, most notably, the Quad (a grouping that includes Australia, Japan, India and the United States) and AUKUS (a trilateral security partnership for the Indo-Pacific region between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States) and vital new trilaterals, including with Japan and South Korea and with South Korea and India. Washington has also deepened its partnership with Vietnam, upgraded alliances with the Philippines and Thailand, and upgraded its engagement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) into a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. President Biden has held two summits with leaders of the Pacific Islands, nations under the greatest threat from climate change and from illegal fishing and other illicit activities in their exclusive economic zones. The administration launched Partners in the Blue Pacific and a new U.S.-Mekong Partnership to build on the progress of the Lower Mekong Initiative.

Such bilateral commitments and multilateral engagements see the United States partnering in meaningful ways on issues that matter in the region, like climate resilience, health and data sharing, to help countries protect their economic interests (for example, with the Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness Initiative). So, a key takeaway for states in the region has been that the United States can step up as an important partner and help build that free and open vision.

Since the launch of the strategy, the world has faced major global shocks, including a war in Ukraine and the Middle East. How does the Indo-Pacific Strategy fare in a time of uncertainty and rapid change?

Freeman: The Indo-Pacific Strategy is proving resilient despite the perverse consequences of these conflicts for U.S. interests in the region. On the one hand, the wars have sharpened the line between the United States and its allies and China and Russia, as China has largely aligned with Russia on the war in Ukraine and the two countries have stood together in condemning the United States’ response to the war in the Middle East. On the other hand, the conflicts have complicated the strategic picture. They have increased the role of Russian oil in the region’s energy supply, reinforcing the importance to New Delhi of its 75-year-old partnership with Moscow, which includes an important defense component.

The conflict in the Middle East, specifically, has exposed divisions across the region: some countries, including India, have good relations with Israel and they have made clear the conflict has not changed this bilateral relationship, while others, often those without diplomatic ties with Israel, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, have taken a very different position. One potentially consequential outcome of the Middle East conflict could be an increase in already building domestic pressure on the government of Japan and perhaps other key U. S. allies that are heavily dependent on Middle East energy resources to separate their Middle East policies from those of the United States.

Galic: The strategy also serves as a clear statement of enduring U.S. focus on the Indo-Pacific region and of the priority the region holds in U.S. policy. The war in Gaza and concerns about a wider conflict in the Middle East certainly require the attention of top policymakers and those of their advisors focused on that region, but this doesn’t mean that all other U.S. foreign policy interests are placed on hold.

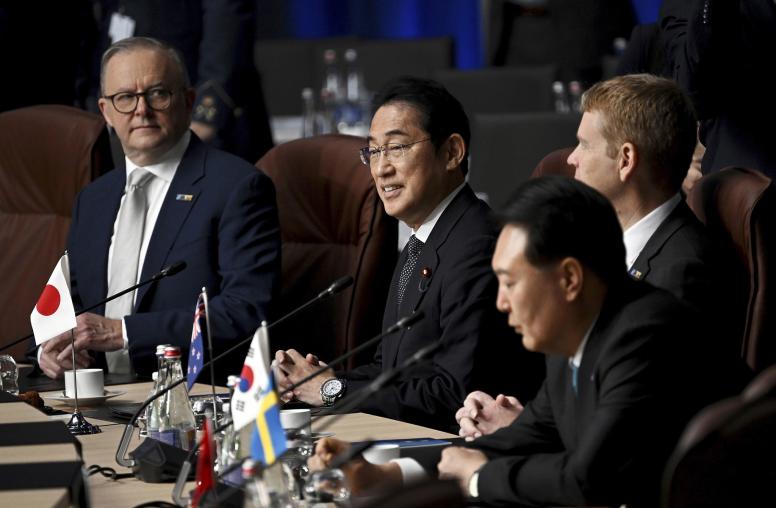

Work on the Indo-Pacific and on the implementation of the Indo-Pacific Strategy continues, and when the focus of the president and top foreign policy actors on the region is needed, it continues, despite the conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine. Biden’s meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping in November, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s state visit to Washington in October and the U.S.-Japan-South Korea leaders’ summit in August are recent examples.

How has the Indo-Pacific Strategy shaped the U.S. relationship with its partners in the region and beyond?

Galic: The strategy places U.S. allies and partners at the forefront of efforts in the Indo-Pacific region. This focus is not new, but it has been fitted into a more comprehensive strategic vision for the region, which aims to address and progress more clearly articulated challenges and goals for U.S. policy in the Indo-Pacific. This provides greater clarity, across the U.S. policy community and abroad, for how to invigorate and adjust our alliances and partnerships. As the strategy notes, “A free and open Indo-Pacific can only be achieved if we build collective capacity for a new age; common action is now a strategic necessity. The alliances, organizations, and rules that the United States and our partners have helped to build must be adapted; where needed, we must update them together. We will pursue this through a latticework of strong and mutually reinforcing coalitions.”

Perhaps, most interestingly, the strategy understands the importance of growing ties between U.S. allies and partners in the region and between regional actors and our allies in Europe and encourages the development of this “latticework.” This is true both in terms of multilateral groupings like the Quad, in which the United States is a direct actor, and in terms of relationships that don’t include the United States, like the European Union’s relations in the region; Australia-Japan, Japan-Philippines and South Korea-Japan ties; and ASEAN engagement with regional partners.

In particular, how has the centrality of U.S.-India relations in the Indo-Pacific Strategy shaped India’s role in the region and multilateral groupings like the Quad?

Markey: By its very name, the Indo-Pacific Strategy placed an important emphasis on India and the Indian Ocean as central to any strategy for what had previously been called “Asia,” or the “Asia-Pacific.” The Biden administration has lived up to its rhetoric in the IPS by devoting a stunning level of time and energy to supporting “a strong India as a partner.” The pace of bilateral and Quad senior-level meetings over the past two years, highlighted by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s state visit to Washington last June, not to mention the proliferation of Quad working groups and routine U.S.-India interactions across bureaucracies, has exceeded any reasonable expectation. Process-wise, the past two years saw the India-U.S. relationship firing on all cylinders.

On matters of defense ties too, the U.S.-India relationship has broken new ground, advancing the IPS’s plan to “steadily advance our Major Defense Partnership with India and support its role as a net security provider.” At the top of the administration’s achievements in this area have been new efforts to enhance bilateral cooperation in critical and emerging technologies, the breakthrough sale of armed drones and the agreement to permit co-production of jet engines to power India’s indigenously manufactured combat aircraft. It would be hard to argue that Washington has not made important strides in the IPS’s plan “to link our defense industrial bases, integrating our defense supply chains, and co-producing key technologies.”

However, despite the significant progress on U.S.-India relations, challenges remain in the relationship. When U.S. prosecutors unsealed an indictment linking Indian officials with a plot to assassinate a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil, the incident raised urgent questions about the extent to which the Indo-Pacific Strategy appropriately identifies India as a “like-minded partner,” and — looking to the future — how Washington should weigh considerations of democracy and values as it continues to build cooperative ties with India and other strategic partners in the Indo-Pacific.

Singh: U.S. relations with partners in the Indo-Pacific have never been stronger, and this is at least in part thanks to the United States committing to the region. China’s overreach — like the pressure Beijing applies to smaller neighbors and the militarization of territorial disputes — has also helped the United States look a lot better by comparison. India’s centrality to the strategy is welcomed for the most part. When looking for investment and technology, for example, many countries in the Indo-Pacific are more comfortable with Indian or Japanese partners than with Chinese. ASEAN partners have been concerned about whether new structures like the Quad will sideline ASEAN in some way, but the United States and its partners have done a lot to demonstrate how the Quad’s purpose is to support the region as a whole.

What are key issues and challenges to watch going forward?

Singh: Resourcing the strategy and demonstrating long-term commitment will both be challenges for the IPS. While the region welcomes U.S. investment and, in particular, its cooperation on technology, energy and infrastructure, the scale of the need will outstrip what the United States and its partners can deliver. Another challenge is more fundamental: in an era of global democratic backsliding, the pursuit of a free and open Indo-Pacific requires work with many nations in the region that are neither free nor open themselves and with democracies that, like others around the world, are under stress.