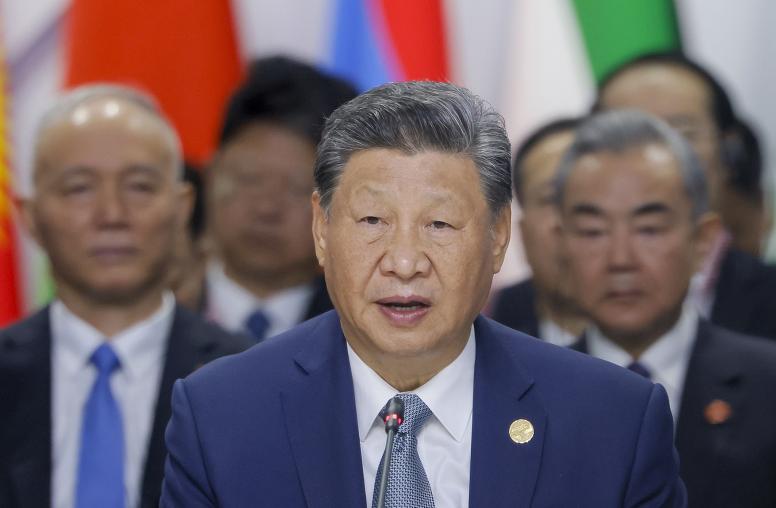

Chinese President Xi Jinping is gathering 29 heads of state and officials from more than 110 countries in Beijing starting May 14 for the first summit of his high-stakes Belt and Road Initiative. The $4 trillion plan offers the promise of economic growth, stability and increased connectivity for countries around the world. But it also faces—and creates—a host of complications for China and the other countries involved.

The investment juggernaut would provide infrastructure, trade, financial, policy and cultural links to 65 countries in Asia, the Middle East, Europe and Africa over the next several decades. It has the potential to connect some of the world’s least developed countries for increased trade and spur their economic growth.

The effort also addresses some of China’s own domestic economic needs: access to natural resources and energy, a market for Chinese companies’ excess construction capacity, and more efficient and cost-effective ways for the country’s western and central provinces to get their goods to market.

Official statements emphasize that the initiative is rooted in the “Silk Road Spirit,”a reference to principles of “peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit.” They consider it China’s “gift” to “benefit people around the world.”

Yet, a lack of transparency about how these projects are identified, designed, approved and implemented raises many questions. The overall levels of investment might give China significant political and economic leverage over participating countries. And China’s investments in ports, rails and road connections could have major military benefits. At the same time, the recipient countries might end up with unsustainable levels of debt, while neglecting to adopt adequate environmental standards and social safeguards.

The initiative is still in its early stages. Despite making it one of the country’s top foreign policy priorities, China has not provided an official map or explained how the different projects fit together, and many of the proposed projects have not broken ground.

Chinese experts insist that most projects are profit-driven, but they concede that some are also pursued with other policy and strategic goals in mind. They are quick to note that the cost-benefit calculations of state-owned enterprises or companies receiving state-backed funding may differ from those of private companies in the West, because the Chinese companies can look for profits in aggregate, balanced over a collection of projects and a longer period of time.

Still, the risks for China are significant. Because the initiative involves some of the world’s most unstable regions, the projects could exacerbate existing tensions or even create new conflicts that overshadow the economic benefits. Without functioning institutions, reliable oversight, adequate regulations and good governance, some recipients may have difficulty absorbing the infusion of development and security assistance.

As more Chinese investments, citizens and companies establish a presence their own borders, instability abroad may make it difficult for Chinese leaders to maintain their principle of non-interference in another country’s internal affairs. If conflict threatens China’s national interests, including physical investments by its companies or the safety of Chinese nationals working abroad, officials in Beijing may feel compelled to respond, thus increasing the risk that China will become involved in conflicts around the globe.