Lessons from a Successful Peace Process in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, 1997-2005

Anthony Regan, Senior Fellow

Report Summary

During his project report, Anthony Regan argued that generally applicable lessons for all peace processes and international interventions cannot be gained from looking at particular cases. While it is useful to examine and engage with other peace processes for international actors as well as local ones, there are no templates for a successful peace process or international intervention. Though it is tempting for international interveners—governments, NGOs, and specialists—to try to identify generally applicable “lessons learned,” this type of thinking leaves little room for a deep understanding of the local dynamics and context which is so necessary, yet difficult and complex, for successful peace processes and constitutions.

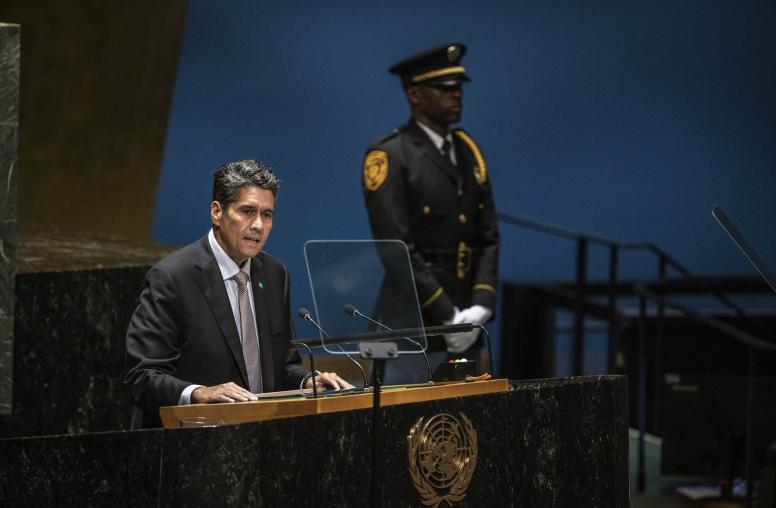

The President of the Bougainville People's Congress, Joseph Kabui, carries a woven basket containing the Bougainville Peace Agreement. (Courtesy Australian Government AusAID)

In the first part of the presentation, Regan elucidated points about the geography, migration history, and linguistic diversity within Papua New Guinea and the province of Bougainville. The long-running peace process resulted in an agreement in 2001 to a referendum on independence for Bougainville within ten to fifteen years of the election of a new Autonomous Bougainville Government, as well as demilitarization and weapons disposal. Bougainville held its first election for the Autonomous Bougainville Government in May-June 2005, and elected President Joseph Kabui, a former Bougainville Revolutionary Arm (BRA) leader and, later, major contributor to the peace process as the head of the Bougainville People’s Congress. While there are significant problems still facing Bougainville in its new autonomy—not least the fact that former BRA commander Francis Ona’s followers remain on the outside—it can still be seen as an extraordinarily successful, though less well known, peace process to date.

Some interesting aspects of the Bougainville peace process and the Bougainville situation generally merit mention, according to Regan. Specifically, the role of culture and indigenous reconciliation practices, local control and ownership of the process, and the generally facilitative and non-dominating role that the international community assumed. For instance, the cultural norm of balanced reciprocity in Bougainvillean traditional societies and the historic practice of locally-generated reconciliation ceremonies led to strong pressure and capacity for grassroots reconciliation to take place in the post-conflict period. Though atrocities did take place during the conflict and social relationships on all levels were damaged, Bougainvilleans largely believe that they have no need of a truth and reconciliation commission so common today in post-conflict situations, because their needs for reconciliation are being addressed by local processes.

Because there was such a deep division in Bougainvillean society after the violent conflict ended, Bougainvilleans had to be able to determine their own parameters for the continuation of conflict at the political level, set the appropriate time limits, and begin forging a system that would work in their unique Melanesian context. Regan noted that outside interveners’ involvement—including that of experts such as himself—risked undermining the salience of local ownership in the process.

Similarly, regarding the role of the international community, Regan shared the fear that highly interventionist attempts at state-building weaken instead of foster local capacity. In Bougainville, the international community, particularly the governments of New Zealand and, later, Australia (both facilitating peace negotiations and providing much support for the unarmed Truce Monitoring Group and Peace Monitoring Group), and the United Nations (providing the UN Political Office in Bougainville, which became the UN Observer Mission in Bougainville) all played discrete but complementary roles which allowed local timetables and dynamics to develop and lead. Regan believes that the international community should take heed of the benefits of a non-intrusive approach and he stressed that the Bougainville conflict was unique in its relatively low intensity; however, in international conflicts where more wide-ranging threats to human rights and security are present, a different approach could be appropriate.

Regan asserted that, while examining other peace processes can be extremely helpful, no generally applicable “lessons learned” can be gleaned because, as in Bougainville, each conflict requires original solutions. He strongly emphasized the importance of understanding the context of conflict which includes people’s historic, geographical, political, cultural, and religious characteristics, and contributes to how they perceive, react to, and behave in conflict. He noted with regret that there is so far very little literature on this aspect of culture and conflict resolution.

Though the international community often seeks out and embraces formulas for interventions, peace processes, and state-building practices (including “robust” peace-keeping, a specific set of requirements for post-conflict constitutions, and strongly interventionist state-building aid), this can be detrimental to the success of the endeavor. Nevertheless, some of the arrangements in the Bougainville Peace Agreement drew on international conflict resolution precedents from New Caledonia, Hong Kong, and Uganda, and Regan believes that examining, though not imitating, the Bougainville peace process and agreement can be useful for the international community and local actors in other conflicts when trying to form a basis for a sustainable state.

Anthony Regan is a constitutional adviser to the Bougainville parties to the Bougainville peace process in Papua New Guinea (1997 to present) and a fellow at the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University in Canberra. Regan has lived and worked in Papua New Guinea and Uganda for over 17 of the 23 years since 1981. He was a government legal adviser in Papua New Guinea and senior lecturer at the Law Faculty at the University of Papua New Guinea. He served as a full-time adviser on postconflict constitutional development to the government of Uganda for over three years in the early 1990s, and was a contributor to a 1995 report by the UN Center for Human Rights in Geneva on the establishment of a Human Rights Commission in Papua New Guinea. He has been involved in the peace processes in the Solomon Islands and Sri Lanka, contributed a research paper to the postconflict constitution-making process in Fiji, and spent two short periods in East Timor advising in the postconflict independence constitution-making process. Regan holds an LL.B. from the University of Adelaide, Australia.