During Sudan’s 2019 revolution—as people mobilized across the country with sit-ins, marches, boycotts, and strikes—artists helped capture the country’s discontent and solidify protesters’ resolve. In particular, artists became an integral part of the months-long sit-in at the military headquarters in Khartoum, which was known as the heart of the revolution until it was violently dispersed by paramilitary forces on June 3, 2019. This immense expression of creativity was both a result of loosening restrictions on freedom of expression and, at the same time, a catalyst for further change.

Throughout Sudan, artists helped spur on conversations about the trajectory of the country and also used murals to share information about dates and times of protests. (See Special Envoy Donald E. Booth’s video statement here.) Jonathan Pinckney, program officer and research lead for USIP’s program on nonviolent action, points out that art has played a role in many major nonviolent struggles as a way to create a shared vocabulary: “Art can provide a unifying center for the many different specific goals and agendas … Few people may read a movement’s hundred-page manifesto, but everyone can recognize the colors, songs, and images that movements draw upon to tell their supporters who they are and what they want."

As for Sudan’s artists themselves, Mustafa Abushamma, owner and founder of Khartoum’s Mojo Gallery, says that the revolution brought a new generation of artists to prominence: “When the revolution happened … the whole world was seeing these amazing murals on the walls in Sudan.” (See USIP’s interview with Mustafa Abushamma here.)

Murals: Keeping Eyes on the Revolution

One of the first forms of art to pop up during the revolution were outdoor murals. As protesters flooded the streets, so too did art installations that depicted a wide array of topics.

Graffiti artist Assil Diab, known as Sudalove, created murals across Khartoum to honor the martyrs of the revolution and of the regime of Omar al-Bashir. Assil describes her work as “a medium to start dialogues and conversations with the community and also speak on behalf of so many people,” noting that upon seeing a mural, “whether you’re with or against the revolution, you are forced to be reminded of what is going on.” (See USIP’s interview with Assil Diab here.)

Families of Sudanese martyrs have found some catharsis in watching or even assisting Assil Diab in creating murals honoring their loved ones. For Pinckney, this comes as no surprise, as “there is something powerful about art that touches the emotions, expresses shared humanity, and invites the participation of lots of people.”

Galal Yousif is internationally recognized for his work across many mediums, including murals. Throughout the revolution, he created several large artworks at well-trafficked locations in Khartoum, including the widely admired mural “The Scream” that was destroyed during the violent crackdown on the Khartoum sit-in.

Although he has been asked to repaint “The Scream,” Yousif maintains that the mural was part of the massacre and that he will not recreate it until there has been justice for the lives lost. Transitional justice is one of the foremost challenges facing the Sudanese government, and many Sudanese are frustrated by the lack of progress to date. Beyond “The Scream,” Yousif has painted other prominent murals in Sudan, including one near the sit-in site and another that he created under Mak Nimr Bridge in Khartoum with a team of volunteers.

Meanwhile, artist Alaa Satir’s murals in the Burri neighborhood of Khartoum highlighted the prominent role of women in the revolution, including a mural of three women captioned “We are the revolution and the revolution continues.” After playing a pivotal part in organizing and leading protests, women have been mostly sidelined during the transitional period—signaling the need for further progress.

Virtual Art: Expanding the Revolution Beyond Sudan’s Borders

Within Sudan, online communication was a critical tool for organizing during the revolution, although efforts were hampered by government-initiated internet outages and blockages of key sites. But for those outside of Sudan—including artist Yasmeen Abdullah—social media campaigns allowed them to express their support. The most widely publicized of these campaigns was “Blue for Sudan,” in which users turned their profiles blue in solidarity following the killing of activist Mohamed Hashim Mattar during the Khartoum military headquarters sit-in crackdown on June 3, 2019.

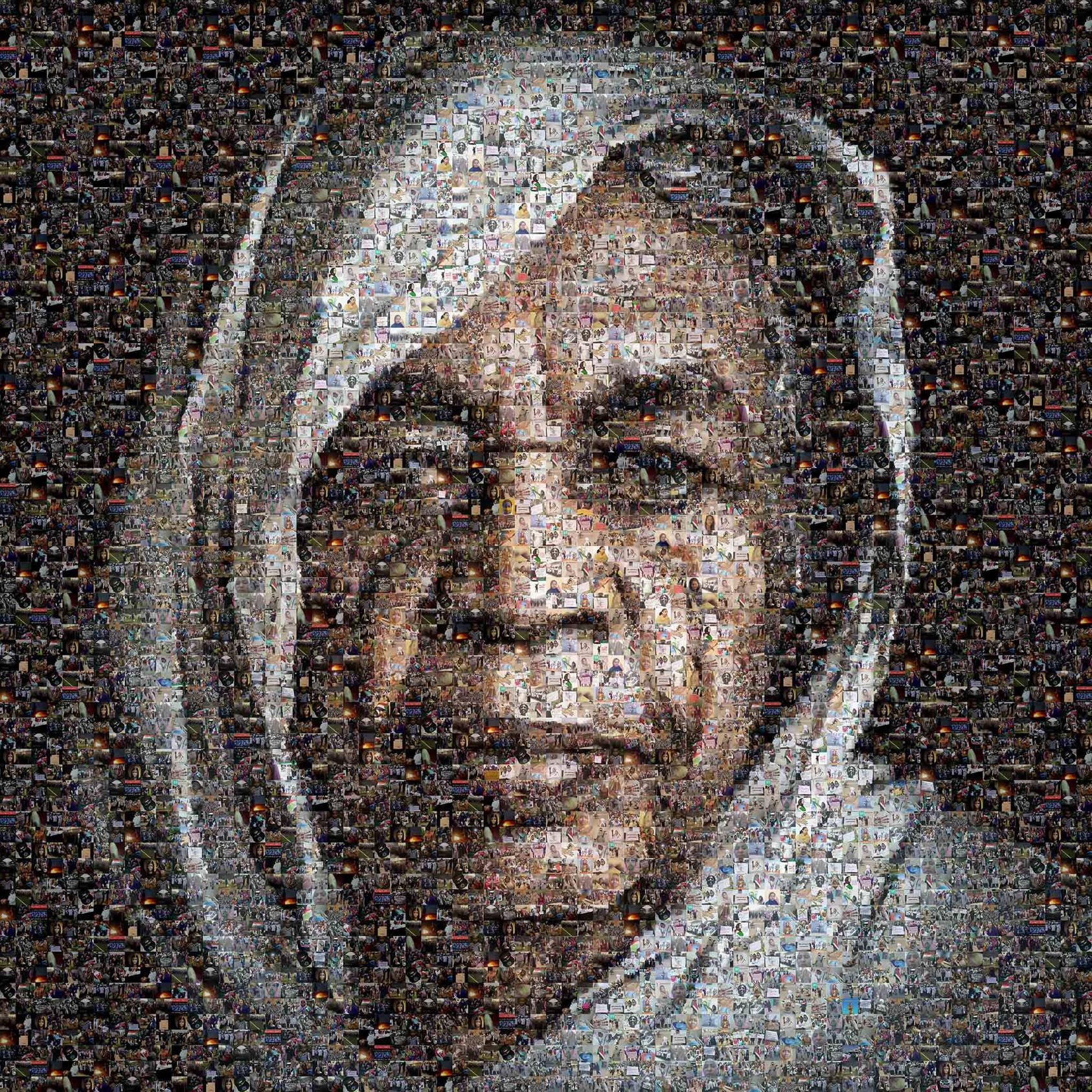

Digital art also opened the doors to experimentation with new mediums. Dubai-based artist Merghani Salih created massive photo mosaics composed of images from the revolution. Describing his process of creation, Merghani said: “I found myself building an archive with all the daily images and videos which were being shared across all social media channels from across Sudan. I then contemplated that if a picture is worth a thousand words, what if that picture was physically made up of one thousand images?”

Revolution on Canvas: Sudan’s Unique Artistic Tradition

Mustafa Abushamma was not surprised that Sudanese artists were able to reach such a wide audience during the revolution, as Sudan is often recognized as an important influence in the development of modern art in Africa through the Khartoum School—Sudan’s modernist art movement founded in 1960. “Sudanese art is a mix of Arab and African, and this is very unique to Sudan,” said Abushamma. “The art coming out of Sudan is not like any art around the world … we see that in the colors, the motifs that we use, and it speaks to a lot of people.”

Abushamma founded his gallery 10 years ago to highlight a diverse slate of artists and to get more Sudanese art into Sudanese homes. He is pleased with the changes that he has seen, noting that increased appreciation for original art means that more artists are able to support themselves. And even amid a tenuous democratic transition, Mustafa is energized for the future when he speaks about the trajectory of young Sudanese artists. Describing the work of Darfuri artist Osman Gouma Ahmed, currently in his early 20s, Mustafa says, “Can you imagine what he will be able to do in 10 years?”

Hussein Merghani is a more seasoned artist who is also featured at Mojo Gallery. His watercolor of the Atbara Train—also known as the Freedom Train—captured one of the most iconic images of the revolution. Hundreds of protestors from Atbara, a city in Sudan’s north that saw some of the earliest protests in the revolution, commandeered a train in April 2019 to travel southward to Khartoum to join the sit-in at the military headquarters. As the train moved slowly along its 200-mile route, Sudanese cheered from alongside. The Atbara Train came to symbolize the broad support for the revolution from across the country. While the Atbara Train watercolor (featured at the top of the page) captures one of the joyous moments of the revolution, Hussein has also depicted the tense everyday moments in the months-long demonstrations, including in a watercolor of a young boy leading a protest with an empty water barrel.

Art in the Transition

Hussein Merghani has used proceeds from his art to pay for continued mural painting around the site of the sit-in at Khartoum’s military headquarters. And he’s not alone—as Sudan shifts from revolution to transition, other artists are supporting social projects throughout the country.

Muralist Assil Diab has adapted her art to the COVID-19 reality, painting murals that encourage mask wearing—including one featuring a diverse group of Sudanese people wearing traditional dress and face masks. As she was painting the mural, she and her team took the opportunity to raise awareness of health precautions with passersby.

Publishing with the hashtag #Khartoon, internationally renowned cartoonist Khalid Albaih levels sharp-witted critiques of injustices around the world. In July, following the army’s statement that citizens publicly criticizing the military could be arrested, he published a widely shared cartoon of a crocodile in military fatigues with large tears rolling down its face. Khalid’s work has mobilized others to use art as a tool to advocate for change in Sudan. And Khalid does not limit his expression to art—he has also written widely, including on the need for further U.S. support to Sudan’s transition.

Sudan’s nonviolent revolution and the creativity that buoyed it are reasons for celebration. But the country faces a myriad of challenges during its transition, including a pandemic and a severe economic crisis that have led to renewed protests in the streets. Additionally, a prominent case where 11 Khartoum artists were jailed this past August has drawn broad condemnation, highlighting the need for legal and judicial reform during the transition to protect freedom of expression.

The work must continue, and there is still an important role for artists—in opening space for public conversations, expressing grievances and hopes, and helping to hold all bodies of the transitional government to account. And the transitional government can honor Sudan’s recent history by preserving revolutionary art for future generations and by nurturing the immense talent and creativity that helped to bring it to power.