What a Russian Nuclear Escalation Would Mean for China and India

If Moscow were to use a nuclear weapon in Ukraine, how would Beijing and New Delhi react?

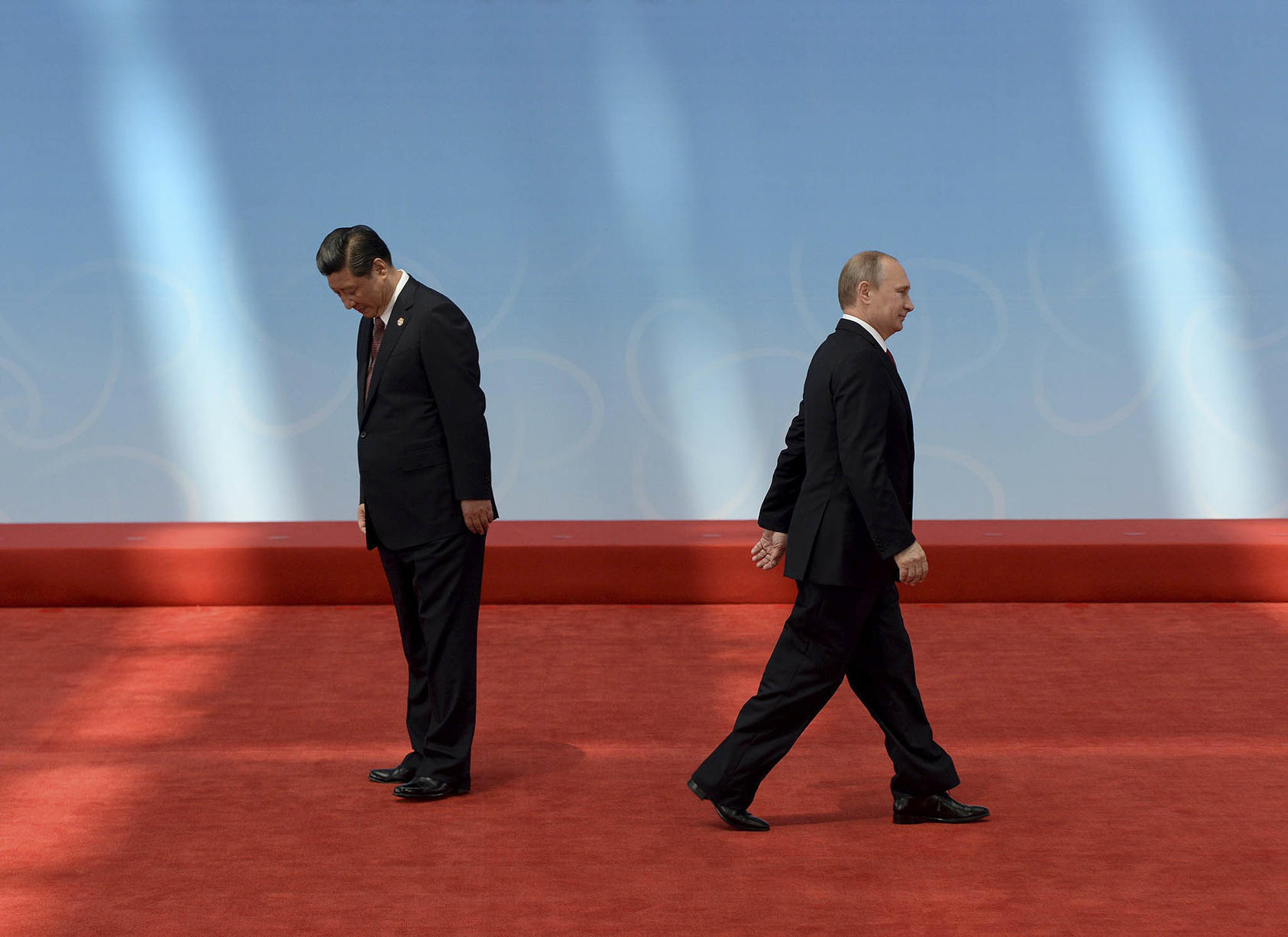

Since Russia began its assault on Ukraine last February, India and China have straddled the fence by hinting at their concerns regarding the war’s global fallout while avoiding direct public criticism of Moscow. Despite rhetorical consternation and calls for a peaceful resolution, neither has shown a willingness to meaningfully push back against Putin’s escalations in Ukraine. Instead, the two Asian nuclear powers are approaching the situation with caution and calculated diplomacy to preserve their own strategic interests — both in Russia and the West.

However, Putin’s nuclear brinksmanship is putting Beijing's and New Delhi’s balancing act in the spotlight. If Putin were to follow through on his numerous threats and use a tactical nuclear weapon in Ukraine, the resulting international outcry could force India and China to reassess their approach to the war. How might the first use of a nuclear weapon in nearly eight decades tip the scales in Beijing and New Delhi?

USIP’s Andrew Scobell, Alex Stephenson and Vikram Singh look at how China and India have navigated the war’s geopolitical repercussions so far, how leaders in Beijing and New Delhi might respond to a Russian nuclear escalation in Ukraine and what effect it would have on their own nuclear doctrines.

How Russia’s Escalation in Ukraine Might Affect China

Scobell and Stephenson: While the West has expressed deep concern over Vladimir Putin’s recent statement that he would not rule out the use of nuclear weapons in the Ukraine conflict, Beijing has remained noticeably silent.

Undoubtedly, the employment of a Russian tactical nuke would pose a dilemma for China. The international backlash alone could force Beijing to rethink its “no limits” partnership with Moscow. But a Russian strike would also go against China’s decades-old nuclear policy.

China’s No-First-Use Policy

Since detonating its first nuclear device in 1964, China has pursued a no-first-use policy, as well as a strategy of deterrence through “assured retaliation.” Thus, for nearly six decades, Chinese leaders have viewed the role of nuclear weapons as limited to self-defense and as distinct from conventional operations and doctrine.

This position was reaffirmed last week by Li Song, the Chinese ambassador for disarmament affairs, who said, “China has solemnly committed to no first use of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstance.”

However, there have been recent signals that Beijing has elevated the role of nuclear weapons and integrated strategic deterrence in its overall military strategy.

For example, China has been growing its nuclear arsenal at an accelerated rate since at least 2021. And in his delivery of the work report at the recent 20th National Party Congress, Xi Jinping also proclaimed the need for China to build a strong “strategic deterrence system.” Instead of pointing to any legitimate change in its position on the use of nuclear weapons, however, these developments point more to Beijing’s changing perception of the international environment. Thus, if Russia employed a tactical nuclear weapon against Ukraine, Beijing would feel the need to publicly react, if only rhetorically.

What a Nuclear Strike Would Mean for China-Russia Relations

Although use of a nuclear weapon by Moscow would thrust Beijing into an extremely awkward situation, this would not necessarily prompt China to completely abandon its strategic partnership with Russia. While the China-Russia strategic partnership is certainly not without issues, it will probably continue as long as leaders in Beijing and Moscow both view the United States as their primary threat — which is unlikely to change anytime soon.

Some have pointed to recent events — such as Putin’s acknowledgement of China’s “questions and concerns” about his war in Ukraine — as evidence of cracks in the Sino-Russian relationship. But that is wishful thinking. In a recent meeting with Russian leaders, China’s third-ranked leader, Li Zhanshu, expressed tacit support for the war in Ukraine, saying, “We fully understand the necessity of all the measures taken by Russian aimed at protecting its key interests.”

In all likelihood, Li’s remarks accurately reflect Beijing’s position on the war. And just last week, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi had a telephone conversation with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov where the two discussed “the high level of mutual trust and firm mutual support between China and Russia,” reaffirming Beijing’s commitment to the Sino-Russian relationship in the wake of Putin’s threats.

The recent work report at the National Party Congress also expressed a bleaker outlook on the international environment than its predecessors. The “period of strategic opportunity,” which has dominated party narratives in the last decade, is now fraught with “risks” and “challenges,” pointing to the threat posed by the United States.

To this end, Beijing is likely to tolerate further escalation in Ukraine short of a nuclear strike. Moreover, one cannot rule out the possibility that China will maintain its alignment with Russia even if the latter employed a tactical nuclear weapon. Beijing’s response may depend on the specific circumstances and Moscow’s justification for its use.

Beijing’s Reaction to International Backlash

Xi Jinping has warned that China must “be prepared to deal with worse-case scenarios, and be ready to withstand high winds, choppy waters and even dangerous storms.” If Russia were to use a tactical nuclear weapon, this would certainly constitute a dangerous storm, if not a worst-case scenario.

Chinese leaders would like to avoid that worst-case scenario if possible. In recent weeks, they have signaled their unease with Russia’s nuclear rhetoric and tried to dissuade Moscow from further threats — albeit indirectly. A small step in the right direction came last week during a bilateral meeting between German Chancellor Olaf Schulz and Xi, where the two leaders discussed the war in Ukraine and reaffirmed that the international community should “oppose the threat or use of nuclear weapons.” Another proactive move would be for a Chinese official to publicly reaffirm the recent joint statement by the five nuclear-weapon states on preventing nuclear war.

China wants to increase its “international standing and influence” and “play a greater role in global governance” according to its recent work report. If Moscow were to actually launch a nuclear strike, the subsequent international backlash would force Beijing to express some level of criticism or condemnation in order to project itself as a responsible great power with moral authority and conviction.

Such a scenario would undoubtedly serve as a major test for Sino-Russian relations, but it is by no means clear that China would completely rupture ties. Over the last decade, Beijing has increasingly used its influence in the United Nations and other multilateral organizations to deftly preempt, avoid or deflect international criticisms on a range of controversial issues — from the mistreatment of Uyghurs and other Muslims in China’s Xinjiang region to Russian atrocities against Ukraine.

Even amid monumental international outrage, Beijing may feel confident enough in its ability to evade substantial blowback that it only offers a rhetorical response to a Russian nuclear strike. Chinese leaders have repeatedly tried to cast the United States and NATO as instigators in the Ukraine conflict to shift attention from Russia. It’s possible the Sino-Russian relationship could weather the storm if Beijing were to spin the resulting outrage in a similar way — and such a route would allow China to position itself as a mature and principled great power intent on seeking win-win solutions.

How Russia’s Nuclear Escalation Might Affect India

Singh: In reacting to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, New Delhi has remained neutral on key votes at the United Nations and called for peace without casting blame on Moscow. Prime Minister Narendra Modi even publicly told Russian President Putin that “today’s era is not the era of war” and encouraged him to bring the conflict to a close. But New Delhi has no intention of severing ties with Moscow, and Indian officials have been transparent about the constraints they operate under, particularly India’s dependence on military equipment of Russian origin.

Instead, Indian officials have held to a middle line throughout the war — sending humanitarian assistance to Ukraine while attempting to offset the economic impact of the war by purchasing Russian energy and fertilizer, among other actions.

But unlike China, which has doubled down on support of Moscow in the weeks after its National Party Congress, Indian leaders view the precedent-breaking assault on Ukraine as a threat to India’s own security. By invading Ukraine, India’s long-time partner has cast aside the core values that India relies on to protect itself from aggression by neighbors. The use of a nuclear weapon by Russia against Ukraine would bring about a crisis for Indian policymakers and make India’s current tightrope walk untenable.

India first tested a nuclear weapon in 1974, calling it a “peaceful nuclear explosion.” Its nuclear doctrine has been to have a minimum credible deterrent and a no-first-use policy. For Indian military planners, nuclear weapons exist to deter combat, not as war-fighting tools. While some Indian leaders have floated the idea of adjusting the no-first-use policy to increase uncertainty and enhance deterrence, especially vis-à-vis Pakistan, no changes have been made to this doctrine.

Moscow is India’s oldest and most reliable defense partner, notwithstanding India’s increased cooperation with the United States and its allies and partners over the past 20 years. But Moscow has deepened ties with China by announcing a “no-limits” partnership as Sino-India ties remain at their lowest point in over 40 years following clashes along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) that claimed 20 Indian soldiers’ lives in 2020. Moscow has also increased outreach to Pakistan, which India views as its most consistent security threat.

Should Moscow move forward with the first use of a nuclear weapon since World War II, it would challenge India in three primary ways:

1. The collapse of global non-proliferation governance

In a normative sense, although it remains outside the U.N. Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) framework, India abides by those long-held principles and wants them to survive. The 191-member NPT itself would be at risk if one of the five recognized nuclear-weapons states made unilateral and offensive use of a nuclear weapon.

This would force a deep reassessment of all Indian nuclear weapons strategy and doctrine. India would have to consider costly investments to upgrade and diversify its own nuclear weapons portfolio, which is smaller than that of either of its nuclear neighbors. With global non-proliferation governance shattered, India would likely seek to lead or actively participate in efforts to rebuild a global consensus against the use of nuclear weapons.

2. Understanding China’s and Pakistan’s responses to nuclear use by Russia

From a demonstration standpoint, India would worry over how China and Pakistan respond. Indian leaders believe their nuclear deterrence with China is stable, even in the aftermath of Chinese aggression and occupation of disputed territory along the Line of Actual Control.

While Indian leaders assume Beijing’s focus will be on implications for Taiwan, they cannot ignore the fact that China claims the entire Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and Beijing may reassess how new uncertainty around nuclear use could serve to coerce or deter. Planners in New Delhi will need to understand how their Chinese counterparts change their thinking about the threat or use of nuclear strikes going forward.

Pakistan does not have a no-first-use doctrine. Indian planners already account for possible Pakistani use of a tactical nuclear device against forward-deployed Indian forces in the case of full-scale war. Indian leaders will expect Putin’s use of a nuclear weapon to increase the likelihood of Pakistani nuclear use. In particular, they will plan against and seek to deter Pakistan from using tactical nukes, possibly on Pakistan’s own territory, to strike or block advancing Indian forces.

Following recent terrorist attacks traced back to Pakistan, India has engaged in counterattacks inside Pakistani territory. During the last crisis between the two South Asian countries, Pakistan retaliated inside Indian-controlled Kashmir and downed an Indian fighter jet. For Indian officials, understanding any changes in Pakistani thinking on nuclear use will be critical to future decisions about how to respond to an attack.

3. The future of India’s relationships with Russia and the West

Finally, and most importantly, India’s relationships with Russia and the West would never be the same after a Russian nuclear attack in Ukraine. The horror and outrage in the United States and Europe would likely lead to a “with us or against us” moment, with Russia ejected fully from the global banking system, including SWIFT, as well as secondary sanctions that are more severe than the toughest sanctions ever placed on Iran.

India would be outraged by Russia violating the longstanding norm against nuclear use, but it would seek a way to preserve core aspects of its relationship with Moscow. For one thing, despite increasing domestic production of arms and diversifying sources to include the United States, Europe and Israel, New Delhi remains deeply dependent on Russian military equipment and would require years or even decades to transition away from them completely. And it would be difficult for Western nations to help India rapidly field everything from new tanks to missiles to submarines. For Indian leaders, navigating the sustainment of their Russian materiel while avoiding western sanctions may prove impossible. The United States, in particular, would probably sanction India like any other country should it continue to purchase Russian arms and spare parts in the aftermath of nuclear use.

China does not rely on Russia for most of its materiel and will likely seek to keep its partnership intact even if Xi criticizes the use of a nuclear weapon. In a worst-case scenario from the U.S. standpoint, China and Russia may partner in response to Western sanctions and invite India to join an alternative economic and political framework that manages transactions without the use of the U.S. dollar or global banking system. China, like India, has been reluctant to violate sanctions against Russia, but both countries have tested mechanisms for settling payments with Russia in local currency or through barter.

Outside of Ukraine itself, India and other low-to-middle income countries are bearing the brunt of the cost of Russia’s aggression. Higher fuel, fertilizer and food costs are driving increases in poverty and hunger. Indian leaders believe they have a better chance of having a positive impact on ending this war by keeping their criticism of Putin mostly private. The specter of nuclear use and catastrophic impact it could have on India’s interests may lead them to push Russia to find a way out of its self-made quagmire.