Islam, Culture and Sexism: Making Change with Religious Learning

Muslim women tap ‘authentic sources’ to take on male dominance

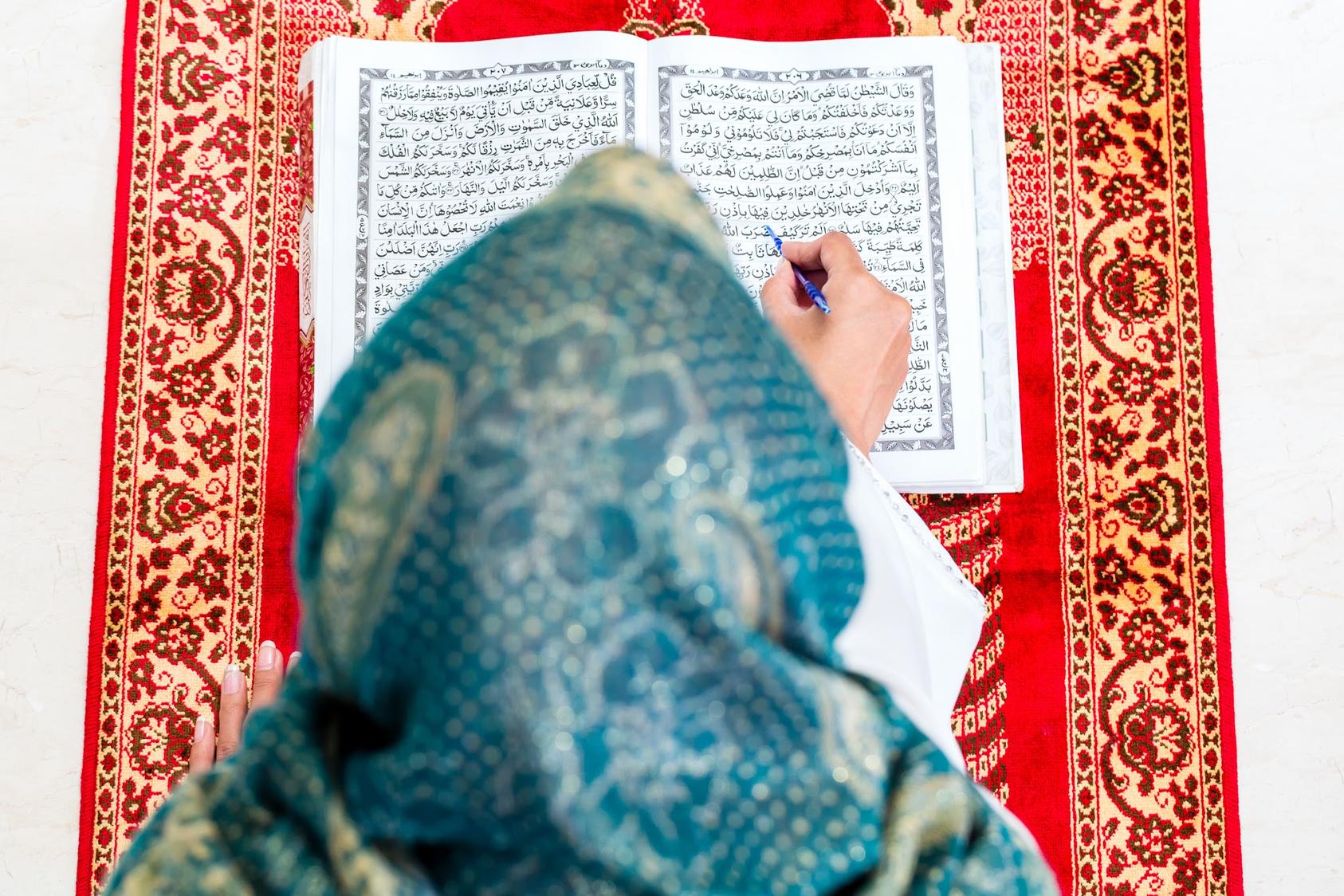

Men in some Muslim societies cite the Islamic faith in defending “honor killings” of women and marriage for child brides. In the West, many commentators proclaim Islam inherently sexist, and some governments ban the veils traditionally worn by many Muslim women. Amid this turmoil, growing numbers of female Islamic scholars cite the Quran to argue that Muslim women are marginalized not by the true tenets of their faith but by patriarchal cultural practices.

The religion of the Prophet Muhammad, they contend, gave women roles as leaders, scholars, and even military advisers. Women owned property independently and had a voice and vote in political affairs centuries before the spread of women’s rights in the West.

To upend traditions that have grown to disadvantage many Muslim women, these activists seek to show that Islam’s foundational texts have been misinterpreted.

“Our greatest asset is Islam,” Aisha Rahman, lawyer and executive director of women’s rights group Karamah.

“Our greatest asset is Islam,” said Aisha Rahman, a lawyer and the executive director of Karamah, an organization that educates Muslim women about Islamic principles of justice and gender equality. “If you are teaching about the Quran you already have the support you need,” Rahman said in a discussion of “Islam, Culture and Sexism” at the U.S. Institute of Peace on October 13.

The program highlighted the work of Dr. Azizah al-Hibri, a longtime University of Richmond law professor and Islamic scholar who in 1993 founded Karamah, naming it with the Arabic word for “dignity.” Al-Hibri’s idea was to provide Muslim women with a solid grounding in religious law, thus letting them challenge male domination on the basis of an accepted belief system. The organization conducts workshops and programs in the United States, Europe and the Middle East, as well as research on women’s rights and Islamic jurisprudence.

“The issue of Islam and women is one of the more contentious areas of misperception and misunderstanding about Islam,” said Lynn Kunkle, grants director of the Washington-based el-Hibri Charitable Foundation, which supports Karamah. “It’s important first to separate Islam from Muslims. Islam is a set of values, beliefs, goals and ideals. Muslims struggle, as all religions do, to implement those ideals.”

Karamah taps into those principles by focusing on “authentic sources” within the faith, Rahman added.

Women from Egypt, Afghanistan and Libya are meeting in Dubai this week to collaborate in protecting women’s rights via Islamic constitutions. Legal advocates, religious scholars and political activists from those countries are working at a USIP-hosted conference to strengthen region-wide efforts to enact and enforce women’s constitutional rights. The conference grew out of a 2013 paper by USIP staff members.

The Karamah model has proven effective in USIP’s own work, said Manal Omar, who leads the Institute’s Center for the Middle East and Africa.

Omar also described how the approach helped a project she worked on years ago in Yemen. Women were trying to win support from religious authorities for a law to raise the legal age of marriage for girls. The proposal ran into a roadblock over its reference to “early” marriage. Interpretation of the word “early” would require numerous rulings by religious courts, the campaigners were told. Drawing on advice from Yemeni religious scholars—and on their own knowledge of Islamic precepts, which bar practices that harm the community—the women replaced “early” with the word “safe,” a standard supported by reams of research on the effects of too-early childbirth. The marriage age for females was raised to 16.

“What does the text actually say?” Omar said. “This is the most useful thing on the ground.”

Religious scholarship that challenges patriarchy also has a place in resisting violent extremism, Omar said.

“The Muslim community across the globe is being called on to wear a critical hat and hold accountable those using the name of Islam to engage in violent action,” she said.

In her own youth, Omar said, she accepted and defended “some pretty silly things about women in Islam, just [parroting] what I had been taught” about traditional roles for women within the faith. Then, she said, Al-Hibri and other Muslim friends “pulled me aside and said, look, it’s okay to be critical,” because much of Muslim cultural tradition about women “doesn’t belong to Islam.” It was the beginning of a critical education that today continues with a scholar who tells her that his job is to make her less vulnerable to the local imam, she said.

Religious education that helps women defend their own authority as community leaders is critical to peacebuilding and responding to violent conflict, said Susan Hayward, USIP’s director of religion and inclusive societies. Women are consistently shown to be more religious than men in belief, devotion and attendance to public rituals, she said. Consequently, they’re important interpreters and transmitters, and potentially transformers, of their societies’ traditions.

“Our approach can be gentle but it must be firm,” Rahman said of Karamah’s work. “We’re not asking for anything. To be included is our God-given right.”