Halting Yemen’s War: U.S. Must Lead, Nobel Peace Laureate Says

Tawakkol Karman Urges a Revived ‘National Dialogue’

Tawakkol Karman, the Yemeni human rights activist who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011, called on the United States to assume a bigger role in trying to revive a political process that might end the war now tearing her country apart. She urged the U.S. government to lead in pressing for a cease-fire and the transformation of Yemen’s militias into political parties.

Speaking at the U.S. Institute of Peace, Karman said the United States should sponsor a renewal of Yemen’s national dialogue—a process that included all of the country’s political forces and that came close to producing a constitution and elections at the end of 2013 under an interim government. “What we want from the U.S. is a bigger role in every respect,” Karman said. “It should help support a civil state and a return to politics.”

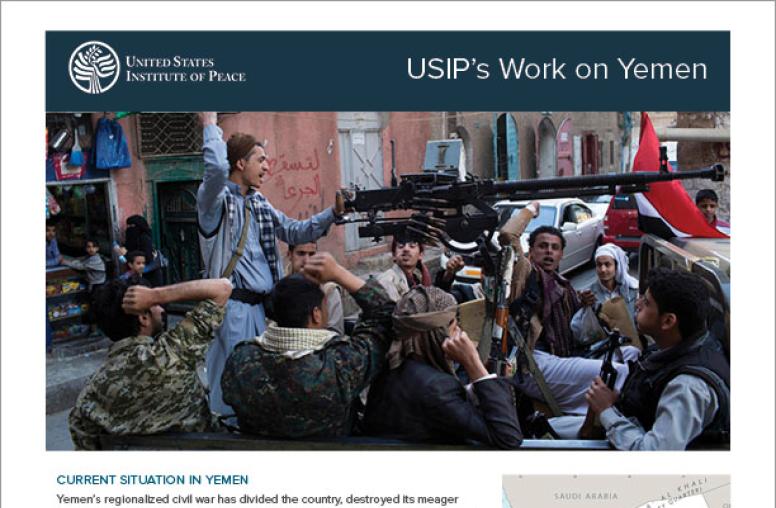

Three years after Arab Spring protests in Yemen toppled the country’s strongman, President Ali Abdullah Saleh, efforts to build a more stable, democratic state fell apart as rising violence erupted into war. Houthi militias from the northwest, allied with forces loyal to Saleh, are fighting a mix of interim government and other forces based more in the south. The violence has displaced an estimated 365,000 people, according to the U.N. refugee agency.

Saudi Arabia and other Arab states have intervened in support of the interim government, headed by President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi. Saudi and other Arab officials have said the Houthi militia is backed by Iran as an attempt to spread Iranian influence in the region.

Discussion during Karman’s appearance focused in part on Yemen’s spiraling humanitarian crisis. The Arab intervention in the war has included a blockade of Yemeni ports. The blockade and related inspections of shipments is hampering assistance work by more than 70 organizations working in the country, said Mohamed Elsanousi of the Network for Religious and Traditional Peacemakers, which co-sponsored the event.

The United Nations World Food Program warned last month that obstacles to getting food assistance into the country are raising the specter of famine for millions. Already 13 million people—half of the population—have insecure supplies of food, the agency said. More than half of Yemenis live in poverty, the World Bank says, most of them small-scale farmers, nomadic herders or other rural people in semi-desert and desert regions.

Yemen’s Arab Spring

Karman, 36, recapped the history of Yemen’s Arab Spring revolution in passionate terms and charted its descent into the current chaos. Known as the “Mother of the Revolution” for her role in the peaceful 2011 uprising that drove Saleh from office, she said the pacific nature of those demonstrations reflected at the time a new politics in Yemen, a country steeped in a tradition of men carrying arms. Her country is home to 26.2 million people, she said, and an estimated 70 million weapons.

“When the people decided to make a revolution for justice, against oppression, the tribes that had made wars against each other for years and years put those weapons away. We all slept and ate in one tent and died together,” as the demonstrators were met with regime violence, she said.

After Saleh stepped down in February 2012, Yemenis—with support from the six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council and the United Nations—established a “national dialogue” to build a new system of government that could assure good governance, anti-corruption measures, human rights protections and a system for transitional justice.

The National Dialogue Conference ended in January 2014 with a compromise deal for a federalized state of several regions—an approach meant to settle power-sharing demands of competing groups, including a long-standing insistence among southern Yemenis for greater autonomy, or even independence. But in the conference’s latter stages, the Houthis—a northwestern-based movement largely of Yemenis from the Zaydi Shia sect—withdrew from the talks after the assassination of their representative there.

Karman said the Houthis walked out in an act of political sabotage and moved to military action with the backing of an expansionist Iran. They did so with support from Saleh, the former strongman and previously their foe.

Violent clashes during 2014 built into the current civil war, with the Houthis seizing the capital, Sanaa, and expanding their control far toward the south. In March, Saudi Arabia intervened against the Houthis, a campaign that the United States has assisted and that has included air strikes, ground troops and the blockade of ports.

Iran’s Role

Karman echoed assertions by Saudi and other Arab officials who say the Houthi military campaign is backed by Iran as part of an Iranian effort to spread its regional influence. “There are lots of statements from commanders and politicians in Iran,” she told the audience. “They talk about Sanaa as the fourth capital they have occupied after Beirut, Damascus and Baghdad, and about building a Persian empire. Saudi Arabia saw the threat and decided to support Hadi.”

Some scholars, including USIP Middle East specialist Robin Wright, say accusations of Iranian involvement have been exaggerated and may divert international policy debates from the deep domestic causes of Yemen’s violence. U.S. officials have accused Iran of involvement in Yemen but also have said the Houthi rebellion has been armed and driven by domestic events.

The United Nations human rights agency and Amnesty International say both the Arab coalition, with its air strikes, and Houthi fighters have committed human rights violations, killing and injuring civilians.

To ease the humanitarian crisis, the ports must be opened, Karman said, but the real need is to end the war and address its causes, including corruption and economic collapse. Even when Saleh was in power Yemen was called a failed state, she noted.

“For now, we have to stop Saleh and the Houthi militias,” she said. “It is not just about food and drink. The war was declared by Saleh and the Houthis and fed by Iran. Humanitarian aid can’t be separated from the war.”

Restore Yemen’s Dialogue?

International pressure and domestic resistance should have one goal, Karman said: Restore the political process that came close to resolving the country’s instability.

She called for a ceasefire in parallel with the militias’ departure from the cities and handing over of their weapons; the transition of the militant forces into political parties; a return to a national dialogue and constitution-drafting; and holding new elections. Interim President Hadi, who has been forced to flee to Saudi Arabia, must return to Yemen and lead during a transitional period, she said.

Karman, the first Arab woman to win a Nobel Peace Prize and founder of the advocacy group Women Journalists Without Chains, said she personally remains committed to non-violence. But the peaceful path is only one form of struggle in Yemen today, alongside what she described as an armed resistance by the population defending the cities.

Karman said she draws strength to continue the political battle and her commitment to peaceful means–despite the odds against both–from a sense of responsibility and belief in herself and the Yemeni people.

“Even when they arrested me, even when they tried to kill me, even when the militia occupied my house–and my house was the first one they occupied,” she said, “Even when they threatened me and my family, always I think, oh my God, they think they will kill my idea?”