Despite Ukraine Focus, Asia-Pacific to Play Prominent Role at NATO Summit

NATO and its Asia-Pacific partners recognize that increased coordination is key to addressing the challenges of an evolving international system.

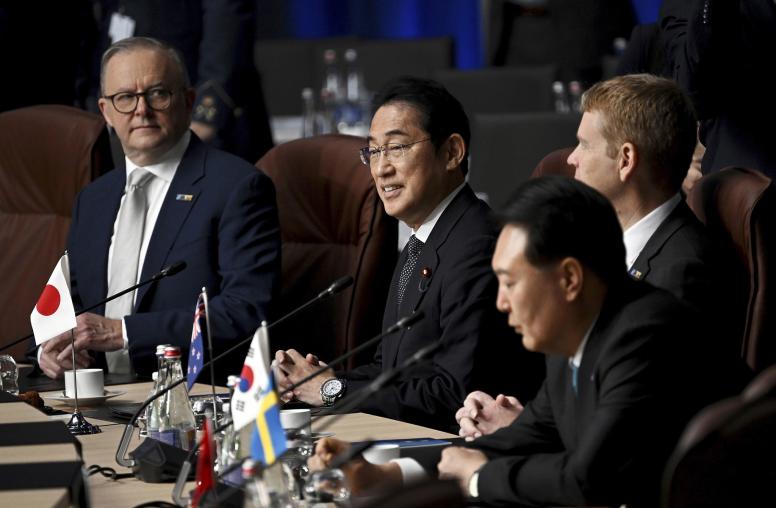

NATO countries meet this week in Madrid, Spain amid Russia’s war on Ukraine, the biggest test the alliance has faced in decades. The summit is expected to focus heavily on demonstrating NATO’s unity, support for Ukraine and the bids of Finland and Sweden — propelled by Russia’s aggressive incursion — to join the alliance. But developments in the Asia-Pacific, chiefly the rise of China, will also be a top item on the agenda, with Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea participating at the leader level for the first time at a NATO summit.

USIP’s Mirna Galic explains how the Asia-Pacific region will factor into the summit and why NATO and its regional partners are stepping up their coordination.

How will the Asia-Pacific feature in NATO’s summit June 29 and 30?

The region will feature in NATO’s summit in two main ways. First, NATO’s regional partners — Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea — have been invited to attend at the head of state and government level, which is new. Although these regional countries have participated in NATO summits before, based on their assistance to NATO missions in Afghanistan, this participation was mostly at a lower minister level. This time, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, New Zealander Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol have all announced plans to attend the summit. Madrid will thus mark a historic occasion with all four of these countries participating in a NATO summit at the leader level for the first time.

The second way that the region will feature is on the topic of China. In a 2019 summit-level communique, NATO acknowledged for the first time that the global scope of China’s rise presented challenges as well as opportunities. By the NATO Summit in Brussels in 2021, NATO’s views on China had begun to take more detailed form. The Brussels Summit Communique issued by NATO heads of state and government noted that China’s “stated ambitions and assertive behavior” presented “systemic challenges to the rules-based international order and to areas relevant to Alliance security,” and detailed areas of concern. The Madrid Summit is likely to further enshrine China in NATO doctrine in the context of renewed great power competition. NATO leaders will endorse the alliance’s new Strategic Concept at the summit, replacing the existing one from 2010, and China is expected to feature in addition to Russia, which is in the current version.

Why are Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea being invited to the NATO summit at the highest level?

NATO’s endeavor to include its Asia-Pacific partners in the Madrid Summit is part of a larger effort in recent years to streamline these partners into NATO’s structures and functions. Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea have been formal partners of NATO since the early 2010s, part of a slate of “partners across the globe,” but they are seen as an increasingly important subset of NATO’s global partners. There is even an informal nickname for these countries, the Asia-Pacific Four or AP4. There are several key reasons for NATO’s special interest in these partner countries.

First is the character of the countries themselves. All four are established democracies that share values with NATO allies, are interested in mitigating international security threats, and have sophisticated and capable militaries. Australia, Japan and South Korea are also U.S. treaty allies, while New Zealand is a close U.S. partner. There are a number of areas where cooperation and coordination between NATO and the Asia-Pacific partners is mutually beneficial, including emerging and disruptive technologies, disinformation, cyber security, maritime security, the rules-based international order and space.

Second is the growing importance of these partner countries’ broader region, the Indo-Pacific. The Indo-Pacific is one of the most dynamic regions in the world, and is expected to be the driver of global economic and technological growth in the decades to come. It is also home to a great power, China, and this takes on added importance as strategic competition between the United States, Russia and China becomes increasingly relevant on the international stage. The significance of the Indo-Pacific region and its impact on global affairs is increasingly realized not only in the United States, but also in Europe.

Third, and relatedly, is the benefit to NATO of having interoperability, coordination and information sharing with countries embedded in the Indo-Pacific region, as well as the messaging and optics on unity this provides. The Asia-Pacific partner countries have a long history of living with China, balancing economic and security imperatives, pushing back on violations of international law, deterring, and dealing with coercive measures, all of which is immensely valuable insight for European partners. Their intelligence and analysis regarding what is happening in the region is likewise of great interest.

Perhaps most importantly, with the reemergence of great power conflict, a strategic competitor sitting in each region, and an evolving Russia-China relationship, there are many common strategic challenges that European and Asia-Pacific partners are having to adapt to that would be valuable for them to discuss together. These include, among others, intermediate-range nuclear forces, missile defense, inter-theater deterrence and defense, and how to push back on great power use of force in contravention of international norms. The last is certainly relevant to the Russian invasion of Ukraine but also has parallels with China and Taiwan, which is why Ukraine is seen as more than a European security issue.

Why do the leaders of Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea, in turn, want to attend the NATO summit?

For many of the same reasons that NATO wants them to be there, not least of all the need to adapt to common strategic challenges related to changes in the international system. Just as NATO sees benefits to engaging with partners in the Asia-Pacific on security issues, Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea see a value to engaging with European partners. NATO gives them a convenient platform from which to do that. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also given many of these countries a sense of vulnerability that European security dynamics have not engendered in far-flung regions since the Cold War. There is a clear cognizance that how the world reacts to Russia’s use of force against Ukraine will inform China’s calculations in the region, including on Taiwan. Attending a NATO summit that will heavily address Russia and Ukraine is a way to project unity and to manage the lessons that China is learning from Russia’s actions and the international response to them.

But the Asia-Pacific partners are also very different countries from one another, and they have their own unique interests in NATO relations. South Korea, for example, is less concerned about China and more concerned about North Korea and its nuclear program, a problem on which it hopes to garner Europe’s attention and assistance. President Yoon has also articulated a vision for his country as a “global pivotal state,” for which a NATO platform provides ample opportunity.

What will be very interesting to see is how much the Asia-Pacific partner countries themselves make use of the AP4 grouping. The grouping is a helpful format for NATO, because these countries are its partners in an important region, but there is little to indicate whether the countries themselves see any significant value in organizing themselves in this way. If a rumored summit between Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea on the sidelines of the NATO summit does take place, it could give an interesting indication of the partner countries’ thinking in this regard.