A Small State Heavyweight? How Singapore Handles U.S.-China Rivalry

Singapore’s form of governance arguably gives the city-state more latitude in addressing U.S.-China competition than other Southeast Asian nations.

Editor’s Note: The following article is part of a new USIP essay series, “Southeast Asia in a World of Strategic Competition.” The opinions expressed in these essays are solely those of the authors and do not represent USIP, or any organization or government.

Alice Ba pertinently observes in her introductory essay to this series that Southeast Asia has become a key arena in the ongoing U.S.-China rivalry; regional countries are under growing pressure to choose between the two powers. For Singapore, this competition has provoked a debate on the extent of agency in the conduct of the city-state’s foreign policy. Two perspectives have emerged in this regard.

The first contends that Singapore has little autonomy, reflecting the structural reality of small states portrayed in the ancient Greek Melian Dialogue: “… as the world goes … while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” This view, which was best captured by former diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, suggests that because Singapore is small, it must behave like small states and “exercise discretion” and “be very restrained in commenting on matters involving great powers.” Mahbubani wrote these in 2017 in response to other Gulf states’ breaking off diplomatic relations with Qatar.

A second view expresses maximalist agency in Singapore’s foreign policy. Propounded by Bilahari Kausikan and other retired Singaporean diplomats, they insist Singapore has not been “cowed or limited by size or geography” or browbeaten and “meekly compliant to the major powers.” Singapore has instead stood up for “its ideals and principles.”

These contrasting viewpoints raises a critical question: How much autonomy does Singapore wield in its foreign policy in this evolving great power competition?

Singapore’s Governance and U.S.-China Competition

If we view agency as the ability of a state to attain its preferred political and foreign policy preferences, and to respond independently to the actions or constraints imposed by others, Singapore has probably greater latitude than most other Southeast Asian states. Governance in Singapore has been dominated by the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) since 1959. The PAP has more than two-thirds presence in parliament and exercises extensive control over the country’s political, economic, social and cultural activities, including its electoral structures and processes. The PAP has avoided overt factionalism through a set of incentives and constraints institutionalized within the party and nationally. Decision-making, including foreign policy, is dominated by technocrats and the political elite, and insulated from public pressure.

The PAP’s political ascendancy allows Singapore to pursue foreign policies unencumbered.

First, to preserve the city-state’s security and sovereignty, Singapore has significantly increased its security cooperation with the United States. Singapore views the United States as indispensable to security and stability in the Indo-Pacific and backed the Obama administration’s rebalance to Asia policy. Since the end of U.S. bases in the Philippines, Singapore has been the anchor for forward U.S. presence in the region, which has been successively augmented over the years. The two countries signed the enhanced bilateral Defense Cooperation Agreement in 2015, and developed a United States-Singapore Strategic Partnership Dialogue “to strengthen cooperation on the range of bilateral, regional and global challenges under the U.S.-Singapore Strategic Partnership.”

Singapore relies on the United States for its advanced military hardware and training. The United States sells sophisticated weaponry through foreign military sales and direct commercial sales programs. Singaporean military personnel participate in training, exercises and professional military exchanges in places like Luke AFB, and Mountain Home AFB Idaho, where Singaporean F-16, AH-64D, and F-15SG pilots train alongside their U.S. counterparts. Pentagon research agencies, including the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Office of Naval Research Global, the Navy Medical Research Center-Asia and the Army International Technology Center-Pacific have offices in the republic and work with Singaporean counterparts on issues of shared military relevance.

Second, the PAP has enacted policies to boost Singapore’s status as a global trading and financial hub. Through low corporate tax rates and other pro-business incentives, Singapore has attracted significant inflows of foreign capital. The republic receives more than $244 billion direct U.S. investment, by far the largest single country investor, accounting for more than 20% of all foreign direct investment (FDI) in Singapore. In the manufacturing sector, U.S. FDI in Singapore is almost 50% more than all Asian investment in that industry. In financial and insurance services, U.S. investment is 60% larger than that of the European Union, which is the second largest investor in that sector. China is Singapore’s largest trading partner, and the city-state is its largest foreign investor. Singapore has seen an influx of affluent mainlanders moving their assets and setting up family offices in Singapore, believing the republic to be a safe haven.

Third, Singapore has cultivated closer ties with middle powers (Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea) and supported open multilateralism to enhance its prosperity and collective security. The republic has been prolific in concluding free trade agreements, several with middle powers and a key proponent of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity.

Fourth, Singapore supports “ASEAN centrality” as a “life raft” amid troubled global times. At the May 2023 ASEAN Summit in Indonesia, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong called for greater economic integration and for ASEAN to be unified, to be cohesive, to be effective and to be central.

Significantly, these security, economic and multilateral arrangements have strengthened the PAP’s “domestic sovereignty” and increased its performance legitimacy. The ruling party’s legitimacy is premised on “instrumental acquiescence,” in which support for the government is premised on its ability to deliver security, political stability and acceptable material standards of living in exchange for the curtailment of certain civil liberties.

China’s Challenges to Singapore’s Sovereignty

However, because of its unique status as the only ethnic Chinese-majority state in Southeast Asia, Singapore faces distinctive challenges to its sovereignty. China, despite Singapore’s consistent denials, insists on referring to it as a “Chinese country” and regularly seeks to influence Singapore’s policy choices, using coercion and pressure.

In response to Singapore’s support for the 2016 South China Sea arbitration ruling which favored the Philippines, and its alleged attempt to include the ruling in the final document of the Non-Aligned Movement summit in Venezuela in September 2016, General Jin Yinan, a senior People's Liberation Army advisor, said Singapore is “meddling in things that did not concern it,” and had to “pay the price for seriously damaging China’s interests.” As such it was “inevitable for China to strike back at Singapore, and not just on the public opinion front.” And because “Singapore has gone thus far, we have got to do something, be it retaliation or sanction. We must express our discontent.”

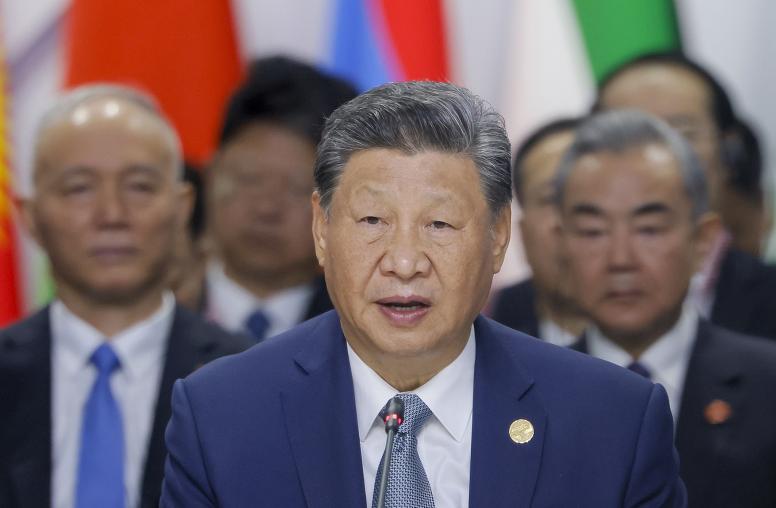

To this end, China exerted pressure on Singapore by detaining its armed forces’ armored Terrex vehicles in Hong Kong in November 2016 and uninviting Singapore’s prime minister to Chinese President Xi Jinping's inaugural Belt and Road summit in 2017.

Beijing has also sought to pressure Singapore’s ethnic Chinese population more directly. It does so through the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and the Singapore Business Federation, by making it harder for businesses to get contracts, licenses and permits, especially in the real estate sector, where Singaporeans hold significant investments in China.

An important constituency China has focused on is ethnic-Chinese seniors, who tend to have a stronger affinity for the mainland. China’s appeals are directed toward supporting ethnic pride and Chinese nationalism, through clan and grassroots organizations, based on locality or kinship (surname). Of note is the China Cultural Center (Zhongguo Wenhua Zhongxin, 中国文化中心), or CCC, which was established in Singapore in 2012. The Singapore CCC promotes cultural activities and exchanges, teaching and training to create a common identity between Chinese China and Chinese Singapore.

Other vectors of influence include direct broadcasts from China Central Television (CCTV) and China Global Television Network (CGTN), both are widely available on Singapore cable TV and carry pro-Beijing and anti-U.S. narratives, and disinformation on social media.

More directly, China has employed espionage. Academic Huang Jing, then director of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s (LKYSPP) Center on Asia and Globalization, was deported after he was accused by the Ministry of Home Affairs of being “an agent of influence of a foreign country.” Ph.D. student Dickson Yeo, also from the LKYSPP, was jailed in the United States and subsequently issued a detention order under Singapore’s Internal Security Act, for acting as an illegal agent of China.

Singapore has attempted to mitigate China’s interference by passing the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Bill.

Key political office holders also assert the republic’s independence and emphasize the importance of upholding sovereignty. At the 2022 National Day Rally, Singapore’s equivalent of the State of the Union, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong warned Singaporeans to be vigilant about messages that are shared on social media and actively guard against hostile foreign influence.

“We need to ask ourselves: where do these messages come from, and what are their intentions? And are we sure we should share such messages with our friends? So please check the facts and do not accept all the information as truths [sic]. We must actively guard against hostile foreign influence operations, regardless of where they originate. Only then, can we safeguard the sovereignty and independence of our nation …”

Although the city-state is clear-eyed about its ability to alter the behavior of the two powers, it has tried to be an “honest broker” and conveyed its concerns about the rising tensions between Beijing and Washington.

Overall, as the United States and China contest for ascendancy in the region, Singapore has had the space to pursue its political and foreign policy preferences. Observers have termed this hedging — a strategy of not choosing between Washington and Beijing while maximizing gains from cooperating with both powers and avoiding confrontation.

Terence Lee, Ph.D. is a visiting associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University and an associate professor in the Department of Political Science at the National University of Singapore.