Part I: Religion in Myanmar

For much of its pre-modern history, the territory known as Myanmar, or Burma, was constituted by kingdoms in a dynamic state of alliances and disputes. This included the Pyu city states just before the Common Era, when Theravada Buddhism from India arrived; the Pagan Kingdom established by the Bamar ethnic group in the 9th century CE; and the kingdoms of Mrauk U (Rakhine), Ava, Hanthawaddy (Mon), the Shan States, and others in the 13th-16th centuries, before the Taungoo and Konbaung dynasties created relatively unified political units that lasted until the British colonial period. These monarchies generally operated via Theravada Buddhist governance. The righteous Buddhist king was considered one who ruled in accordance with the “dhamma” (Buddhist teachings or law), helped maintain order within the “Sangha” (monastic community), and protected and propagated the Buddhist “sasana”(the entirety of the Buddhist tradition).

The British Empire conquered Burmese territory in a succession of wars throughout the 19th century. In establishing new forms of British governance, colonial rulers disrupted the traditional relationship between religious and political institutions. They refused to appoint a “sangharaja,” the political head who oversees the Sangha, and severed the patronage relationship between state and Sangha.

The result was a perceived decline in the sasana’s well-being. An influx of practitioners of other faiths — especially Christians and Muslims — exacerbated anxiety about Buddhism’s weakening influence on social and political life and sparked a Buddhist revival movement.

While the first constitution for the newly independent state in 1948 preserved this separation between religion and state, the country’s first prime minister, U Nu, himself a devout Buddhist, sought to establish Buddhism as the official religion of the state. This, among other issues, upset non-Bamar ethnic groups, particularly those for whom Buddhism was no longer the prevailing religion, and fueled the fire of ethnic insurgencies. In 1962, these ethnic rebellions led the military to its first coup.

The military ruled autocratically for the subsequent five decades, responding violently to persistent democratic activism in the heartland and multiple ethnic armed insurgencies in the periphery.

Democratic movements during this period, including the mass uprising in 1988 led by Aung San Suu Kyi and the 2007 Saffron Revolution, were associated primarily with Bamar Buddhists, with monks playing important leadership roles. In 2008, the military regime began to lay the foundation for establishing its path to a “discipline flourishing democracy” through a series of reforms.

During this quasi-democratic period from 2011-2021, the country engaged the international community robustly, the military pursued cease-fires with some ethnic armed groups, and the opposition National League of Democracy (NLD) operated freely under the leadership Aung San Suu Kyi, who was released from house arrest. But this period was still marred by violence, including the 2012 rise and spread of intercommunal violence targeting Muslim communities and the brutal 2016 and 2017 assaults on the Rohingya Muslim community that led to their mass displacement into Bangladesh, which was designated a genocide by the United States. In February 2021, the military staged another coup, re-arresting Aung San Suu Kyi and re-establishing authoritarian rule.

Religious Demographics

The majority religion in Myanmar today is Theravada Buddhism. Prior to Buddhism’s arrival, many populations practiced a land-based, animist religion referred to as Natworship (“nat”refers to the divine spirits constituting this system’s pantheon). Nat worship continues to be practiced by many communities, sometimes as a distinct practice but often incorporated into other religions’ practices, particularly Buddhist.

The pre-colonial period saw the arrival of other religions, including the Islam of Arab traders as early as the 7th century CE and Christian missionaries in the 17th century. Both these religions’ populations increased markedly during the colonial period, when Muslims (as well as a smaller number of Hindus) migrated from India to work in the colonial administrative system, and Christian missionaries from England and America found amenable audiences for conversion among some of the territory’s ethnic communities (namely the Karen, Kachin and Chin).

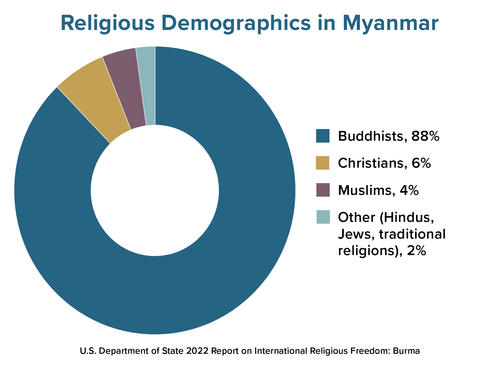

As with many countries, determining the exact demographic numbers of religious populations in Myanmar is a fraught exercise, marred by politics, lack of census data from areas experiencing severe violent conflict, and sensitivities about self-reporting religious identity. Thus, demographic numbers should always be taken with a grain of salt.

Ethnic identity overlaps with — and complicates — religious identity boundaries. Ethnic Bamar constitute approximately 68 percent of the population. Other major ethnic groups include the Shan (9 percent), Karen (7 percent), Rakhine (4 percent), Mon (2 percent), and Kachin (1.5 percent).

In total, the state recognizes 135 ethnic groups in the country. Theravada Buddhism is the primary religion of the Bamar ethnic majority and of many non-Bamar, comprising 88 percent of the population.

Some ethnic minority groups, including the Karen, Kachin and Chin, have sizeable or even majority Christian populations; the overall percentage of Christians in the population is 6 percent (majority Baptist).

Muslims (primarily Sunni) comprise 4 percent and are themselves constituted by ethnic diversity (namely Kamein, Rohingya and those who identify as ethnically Indian; the overall percentage of Muslims in the country is certainly lower than 4 percent now due to Rohingyas’ expulsion).

The remaining 3 percent includes practitioners of Nat worship and other religions, including Hindus, Sikh, Bahai, Jews and the unaffiliated. Depending on the social and political context, competing ethnic identities and historical grievances may diminish solidarity around shared religious identities.

For example, there are armed groups in Karen and Rakhine states associated with their Buddhist populations that have fought — or are fighting — the Myanmar army. At times, including in recent years, non-Bamar groups have come together across religious divides to resist the state. At other times, shared religious identity has been marshalled to rally collective action against a religious or ethnic group deemed a threat, as has been seen multiple times throughout Burma’s modern history when Buddhists of different ethnic backgrounds aligned against Muslims.

Legal Status of Religion

Myanmar’s 1947 constitution granted Buddhism a “special position” as the majority religion. Similarly, the current constitution, established in 2008, grants Buddhism a special status but also conveys official recognition to Islam, Christianity, Hinduism and Nat worship. It contains provisions guaranteeing religious freedom but limits it for public order, morality and health. Notably, Buddhist monks are prohibited from voting or running for political office (and there are reports of clerics from other religions being barred from voting), as is the abuse of religion for political purposes.

Despite the guarantee of religious freedom, many religious and ethnic minorities in Myanmar have seen their religious freedom circumscribed for decades due to the discriminatory nature or application of legal protections. These communities face massive hurdles to secure approval for repairing or constructing religious buildings, for example. Anti-defamation laws are often mobilized against non-Buddhists accused of defaming Buddhism, while Buddhist leaders who defame other religions do so with relative impunity.

Historically, governing authorities and systems have privileged Buddhism. In keeping with Theravada Buddhist kingship models, the Buddhist ruler, whether a king or government, is understood by many Buddhists to shoulder the duty of serving the sasana through acts of patronage, promotion of monastic education, and more broadly by supporting and regulating the Sangha. This conception is reflected in the “special” constitutional status of Buddhism and plays out in the practices of certain government bodies, including the Ministry of Religion.

In the 1990s, the military regime created the Department of the Promotion and Propagation of the Sasana under the Ministry of Religious Affairs. This department actively promotes Buddhist missionary projects in ethnic minority areas. In 2016, the NLD-led government combined the Ministry of Religious Affairs and the Ministry of Culture into the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture (MORAC). MORAC is responsible for dealing with Sangha matters in consultation with the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee (often referred to as the MaHaNa), a state-appointed monastic body, and with religious minority affairs. However, the work of MORAC is often viewed by non-Buddhists as privileging and representing Buddhism.

Key Religious Actors

Sitagu Sayadaw

The most well-known Buddhist monk in Myanmar is arguably Sitagu Sayadaw, founder of the Sitagu Buddhist Academy and a free hospital outside Mandalay. Sitagu Sayadaw rose to prominence after the 2008 Cyclone Nargis, when he established relief centers to support those affected. His contributions to humanitarian relief, education, health and his religious activities (he’s regarded as a powerful preacher and has participated in interreligious activities) bolster his influence. In 2014, he co-founded MaBaTha (described further below). In 2017, many criticized Sitagu Sayadaw's spiritual justification for the military's genocidal campaign against the Rohingya. He often appears with 2021 coup leader Min Aung Hlaing and other senior monks in the state newspaper and preaches regularly to troops.

Cardinal Bo

Charles Bo has served as the Catholic Archbishop of Yangon since 2003 and was elevated to cardinal by Pope Francis in 2015. Cardinal Bo has played a prominent role responding to social and political events and tensions in Myanmar, issuing statements and participating in peace-related activities. In 2016, during the assault on the Rohingya community, Cardinal Bo was one of the few senior religious leaders to speak in defense of the Rohingya. He has engaged publicly with members of the NLD, including Aung San Suu Kyi, and with military leaders, including Min Aung Hlaing.

MaHaNa

Established by military rulers in 1980, the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, often referred to as the MaHaNa, is a state-sponsored monastic body that oversees Sangha affairs across the country. The MaHaNa is the highest form of Sangha organization and works under the control of the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture. The 47 members of the MaHaNa, elected by the government, work mostly on administrative matters, including resolving disputes of monasteries, addressing misbehaviors of Sangha, and performing ceremonial roles. A system of Buddhist courts managed by the MaHaNa rule on violations of monastic law. Although the MaHaNa initially made statements criticizing the 2021 military coup, it has since remained quiet.

Religion and Public Life

Religion plays a critical role Burmese public life, in ways both obvious and subtle. For the majority, Buddhism is an important moral touchstone for the state and society, but leaders of all faiths play influential roles as social and political commentators and mobilizers. Moreover, religious practices, networks and institutions play vital social service delivery roles in the country, including for health care, disaster response and education.

From 2009-2019, Myanmar ranked as the second-most charitable country in the world, according to the World Giving Index. This is linked to two factors: First, financial and other material donation, called dana, is a central component of daily Theravada Buddhist practice. Second, in the absence of adequate social services provided under the military regime, Burmese communities established volunteer networks and systems to provide mutual aid. Sometimes referred to by the Pali term “parahita,” these volunteer service networks aid communities impacted by natural disasters and provide medical care in rural areas — often operating clinics out of monasteries or other religious sites and running a network of schools that operate at monasteries to provide free education to youth who cannot afford or access government-run public schools.

These forms of community-based social service provision are found across ethnic and religious groups, often connected to religious institutions and leaders who provide space and help organize the efforts. In places where violence is recurrent, religious communities often provide refuge for the displaced, such as in Kachin State where the Catholic Church, Kachin Baptist Convention, and Buddhist monasteries run displaced persons camps.

As noted, there is an entangled relationship between state and religion regarding authority and institutions, particularly with Buddhism. In addition to those state institutions that manage religious affairs, namely the MaHaNa and MORAC, religious clerics and representatives from religious organizations are frequent commentators on social and political events, with considerable influence on national conversations.

They also consult with political leaders on a regular basis. Well-known leaders like Cardinal Bo or Sitagu Sayadaw issue regular statements — verbal and written — responding to current political events, as do national religious non-governmental organizing bodies such as the Myanmar Council of Churches or the Islamic Religious Affairs Council. Locally, religious leaders and organizations do the same, particularly among Buddhists and Christians. For example, in Kachin State, the Kachin Baptist Convention wields considerable influence.

Religious leaders, organizations and networks have been active participants in civic mobilization both historically and in recent decades. Buddhist monastics played critical roles in the movement for independence and subsequent democratic movements. However, Buddhist organizations have also been involved in forms of civic and legislative activism that target vulnerable groups. For example, the Buddhist 969 Movement that arose in 2012 and a closely-linked successor organization, the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion (commonly referred to by the acronym MaBaTha), advocated for boycotts of Muslim businesses and for the passage of four discriminatory laws in 2015 that — among other things — restricted the right of Buddhist women to marry non-Buddhist men. In 2017, after the NLD assumed power, the MaHaNa disbanded MaBaTha, citing violation of Buddhist law.

Transnational Religious Factors

The religions of Myanmar have influence beyond the country’s borders, and religious dynamics outside Myanmar in turn shape and influence religions within it. Three examples are worth noting. First, the lay practice of insight meditation, popularized by historic figures Ledi Sayadaw, Mahasi Sayadaw, and S. N. Goenka, has been exported worldwide. Today, insight meditation centers and their teachers around the world often have Burmese Buddhist connections. Second, the Sangha in Burma feels a deep historical and contemporary connection to the Sangha in Sri Lanka. This manifests in tangible ways — Burmese monastics will often study in Sri Lanka — and in less tangible ways: Monastics in each country follow events affecting the other closely, sometimes mimicking each other’s participation in social and political movements.

Finally, there are strong transnational networks of Christian solidarity with oppressed ethnic communities in Burma, particularly other Christians (the Karen, Kachin and Chin). This support comes through both denominational connections (for example, the American Baptist Church or the Catholic Church) and diaspora activity as well as transnational religious freedom activism and faith-based humanitarian assistance (the Free Burma Rangers, formed in 1997, are a prominent example of the latter). Religious freedom activism has also mobilized to support Muslim and other religious minority communities, particularly the Rohingya, most recently through international criminal procedures.

Interreligious Affairs

Interreligious activity was suppressed under previous military rule. The devastating Cyclone Nargis in 2008 marks something of a historic shift. The military regime refused access to international humanitarian organizations and was slow to organize its relief efforts. But Buddhist and Christian networks, leaders and institutions mobilized swiftly and cooperatively.

In the space provided by the quasi-democratic reform in 2011, a new era of interreligious work emerged. Then-President U Thein Sein supported interfaith friendship groups organized in part through the YMCA. The international Religions for Peace organization helped to establish an Interfaith Council of Myanmar comprising representatives of key religious organizations. National organizations that were engaged in peace and human rights strengthened their efforts at interreligious bridge-building. And, when forms of hate speech and communal violence between Buddhist and Muslim communities broke out in 2012, more interreligious work was undertaken, especially by young people.

Country-specific Religious Issues or Characteristics

As in other places, normative religious practice is highly gendered in Burma. Among Buddhists, only men can receive full monastic ordination and enjoy its social and spiritual benefits. Women can take monastic vows and live communally as a monastics called “thilashin.” But because they are not fully ordained, thilashin are considered subordinate to male monastics and receive less support from the lay community. Among Christians, ordination of women as priests or ministers varies. Karen Baptist women can be ordained, while Kachin Baptist women cannot. Catholic women can serve as nuns but not priests. While Muslim and Hindu women are traditionally barred from serving in formal roles, they can and do serve as prominent heads of religious organizations and networks and as religious instructors to children.

Part II: Religion and Conflict

Myanmar has suffered repressive military rule and numerous civil wars between the state and ethnic armed groups for well over half a century. Conflicts in Myanmar are deeply shaped by ethnic and religious identity. The Bamar ethnic group has enjoyed a privileged position in society and governance, while other ethnic groups have endured systemic oppression and human rights violations (though the Bamar community has also suffered greatly under military rule).

Alongside ethnic cleavages, religious identity-based discrimination has contributed to the perpetuation of conflicts. The Bamar community has often projected Buddhism as essential to Burmese national identity and governance, alienating other religious and ethnic groups. In this overarching way — as a dimension of nation-building projects and social movements that privilege Bamar Buddhists and Buddhism at the expense of other communities and religions — religious ideas, actors and identity have played a role in fueling multiple forms of violence in Myanmar.

At the same time, religious actors, ideas, practices and institutions (sometimes the very same ones that have fueled violence) have played critical roles advancing democratic reform; mediating peace processes and de-escalating tensions between groups; championing a pluralist national vision; and responding to the needs of suffering communities. The story of religion, violence and peace in Myanmar is one of significant importance as well as religions’ deeply ambivalent and complex influence and must be understood as such.

While ethnic groups on the periphery of the state had already expressed wariness and mobilized to defend their communities prior to independence, the start of Myanmar’s civil war is often linked to the first prime minister, U Nu, who undertook efforts to make Buddhism a state religion in 1960. This project was supported by the many Buddhists who felt their religion was suppressed during colonial rule.

In response, religious and ethnic minorities such as the Kachin raised concerns about an imposition of Buddhism on minorities that violated the Panglong Agreement reached prior to the formation of the union by General Aung San, leader of the independence movement. The Panglong Agreement promised autonomy and self-determination for ethnic groups, including protections for their languages, cultures and religions. U Nu’s decision to promulgate Buddhism as the state religion was one of the primary factors for the formation of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in 1961. Non-Bamar ethnic groups — including, notably, some Buddhists — saw making Buddhism a state religion as part of the Burmanization (or Bamarization) of the country, which they sought to prevent by armed rebellion. In time, ethnic-based armed groups mobilized throughout the periphery, sparking insurgencies — many of which continue to the present moment.

Religious actors have at times played a mediating role in these conflicts, negotiating cease-fires between military and ethnic armed groups. For example, in Kachin State, Reverend Saboi Jum, the general-secretary of the Kachin Baptist Convention, facilitated a cease-fire agreement between the Kachin Independence Army (KIO) and the military government in February 1994. His daughter, Ja Nan, played a mediating role decades later in renewed cease-fire talks under President U Thein Sein.

In Karen State, where armed conflict and human rights violations have caused internal mass displacement and heavy flows of refugees into neighboring Thailand, Buddhist monks have played a prominent role in the long-running conflict between the ethnic-armed Karen National Union (KNU) and Myanmar’s military. In 1994, the Karen ethnic armed group split into two, the mostly Christian-led Karen National Union (KNU) and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA). Buddhist monk U Thuzana led the formation of the DKBA. Under his patronage, the DKBA signed a cease-fire agreement with the military government in 1994. In a later peace process in Karen State, a number of Buddhist and Christian leaders formed the Karen State Peace Committee and mediated between Karen armed groups and the military government.

In Chin State, Christian pastors have similarly played periodic roles as shuttle diplomats and peace mediators amid war between the Chin National Army and the Myanmar military.

In addition to the multiple civil wars between the Myanmar military and ethnic armed groups that have been ongoing since as early as 1949, Myanmar has also experienced periodic episodes of communal violence.

In recent decades, communal violence has affected Muslim communities disproportionately. It first manifested under colonial rule, when rioting crowds targeted Muslim businesses and communities as a stand-in for the British colonizers who’d encouraged their migration to the country. In more recent decades, episodes of violence throughout the center of the country (Meikhtila in 2013 and Mandalay in 2014, for example) have been fueled by geopolitical Islamophobic narratives and localized rumors (often fueled by the military) about Burmese Muslims’ supposed agenda to destroy Buddhism.

Underneath and behind these rumors are the persistent claim that Muslims, like Christians, are more loyal to foreign agendas and interests than to the Burmese nation-state. Monastic activism groups like 969 and MaBaTha, which arose during the quasi-democratic period from 2011-2021 and supported by members of the Myanmar military, perpetuated these Islamophobic narratives — sparking episodes of violence against Muslims (including the Rohingya genocide) and exclusionary legislation restricting Muslims’ and women’s rights. Notably, MaBaTha has been essentially dormant since 2019. There are also individual examples of Buddhist monks and other religious leaders who intervened during these episodes of communal violence to de-escalate tensions and protect Muslim communities, such as U Withudda, who sheltered some 800 Muslims in his monastery in Meikhtila in 2013.

In February 2021, the Myanmar military staged another coup, sacking democratically elected leaders, re-arresting opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and re-imposing draconian military rule. Civil society responded swiftly and massively, launching a civil disobedience movement in which many employees of public institutions participated in massive protests across the country. These protests were largely led by young people — a new generation of democratic activists who sought to replace the largely Bamar-led democratic movement of the past with more diverse leadership structure and vision for a future democratic Myanmar.

Religious leaders of all faiths — especially younger leaders — participated in the protests, often following the lead of the young organizers. Forms of religious symbolism and practice were present throughout the protests, such as the act of overturning of the Buddhist alms bowl to demonstrate condemnation of the military, the chanting of Buddhist scripture to bestow protection on protestors, and the lifting up of the Christian cross, among others.

Muslim scholars, who in the past feared participation in such protests, joined in at the encouragement of protest leaders. Notably, these young protestors condemned by name Buddhist monks who colluded with and supported military leaders. Despite the important presence of religion in the anti-coup protests, it is noteworthy how few religious clerics played leadership roles — a departure from the past, when clerics have played more significant roles at the helm of anti-colonial and democratic movements.

In the years since 2021, the military has sought to corral influential religious leadership to justify its actions. General Min Aung Hlaing, the military leader of the junta, has deepened ties with influential religious leaders. In March 2022, Sitagu Sayadaw praised the coup leaders as a “king or head of state of great generosity and wisdom.” Min Aung Hlaing also participates in acts of Buddhist patronage, such as sponsoring the creation of a replica of the sacred Shwedagon Pagoda at a Buddhist temple in Russia.

Acts like these demonstrate the military’s attempts to link its legitimacy domestically to the protection and promotion of Buddhism. But military leaders don’t just engage with Buddhist leaders. In December 2022, Cardinal Charles Bo welcomed the coup leaders and prayed for peace, prosperity and happiness for the people of Myanmar. Simultaneous to this meeting with influential religious leaders, the Myanmar army burned down hundreds of religious buildings perceived to be supportive of the anti-coup movement, including monasteries, churches and mosques across the country. Several prominent religious clerics have been arrested — including Myawaddy Sayadaw who died not long after his release — and the former president of the Kachin Baptist Convention, Pastor Hkalam Samon.

Conclusion: Looking Ahead

While the situation in Myanmar is overwhelmingly dire, there are some glimmers of hope. Despite the military’s long history of discrimination and violence against religious and ethnic minorities and its attempts to stir interreligious discord, the coup unified different religious groups in political and social solidarity in a way never seen before.

Buddhists, Muslims, Christians, Hindus and others participated cooperatively in the anti-coup protests across the country. This vision of interreligious solidarity at the protests is reflected in the current political opposition movement and framework. Myanmar’s National Unity Government (NUG), formed after the coup as a democratic alternative to military rule, has promised to govern in a pluralist manner and repeal the problematic 1982 citizenship law that excludes Rohingya from citizenship. This vision and commitment to interreligious solidarity offers positive hope for a more just and inclusive society. However, much remains to be worked out by the NUG and others to determine the particulars of a state structure, constitution and society that dampens religious discrimination.

This primer was drafted in June 2023 by Susan Hayward and Htay Wai Naing, both of Harvard Divinity School’s Religion and Public Life Program.