Yemen

Religion, Peace and Conflict Country Profile

Yemen’s brutal civil war has raged for the better part of a decade, creating one of the largest humanitarian tragedies of modern times. While religion is not a primary driver of conflict in Yemen, major groups involved in the fighting do differ in terms of religious identity, and this fact means that religion has taken on salience in terms of how the conflict is perceived and understood by some observers. The purpose of this profile is to assist those looking for a more nuanced and thorough understanding of how religion and conflict interact in Yemen. It does this by surveying the religious composition of the country, explaining the role that religion has played in the war, and assessing whether and how religion might contribute to peacebuilding in Yemen.

Part I: Religion in Yemen

Religious Demographics

Yemen is a predominantly Muslim country. Non-Muslim religious minorities make up a small percentage of the overall population — including a minimal Christian population of unknown size and a few thousand Baha'is. At one time, Yemen was home to one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, but its numbers have dwindled significantly in the past several decades.

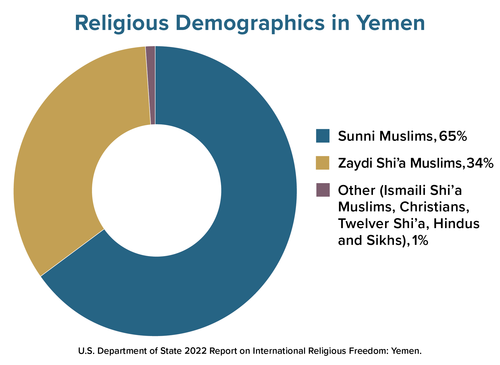

Muslims in Yemen are divided into Sunnis — the vast majority of whom follow the Shafi’i school of jurisprudence — who make up approximately two-thirds of the population, and several Shia groups: Zaydis, comprising approximately one-third of the population; about 100,000 Ismailis; and a very small Khoja community (followers of Twelver Shia) in the city of Aden. Another relevant Sunni trend is Salafism, whose origins as a highly conservative and doctrinally rigid (albeit mostly apolitical) movement date back to the 1980s. More recently, Yemeni Salafis have taken a more prominent political role with backing from external powers such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who view Salafism’s anti-Shia orientation as useful for counterbalancing Iranian influence in Yemen.

Shia in Yemen

Yemen’s positioning as a remote, mountainous country has made it possible historically for a minority Shia population to flourish in parallel to the rise and fall of Sunni caliphs in the broader Middle East. The competing religious histories of Sunni and Shia communities continue to influence modern Yemen and regional identities.

Shia in Yemen is divided into two main branches which differ significantly in terms of religious doctrine: Zaydism and Ismailism. These groups are distinct from the largest Shia group globally, Twelver Shia, which is the dominant sect in Iran, Iraq, Bahrain and most other countries with significant Shia populations.

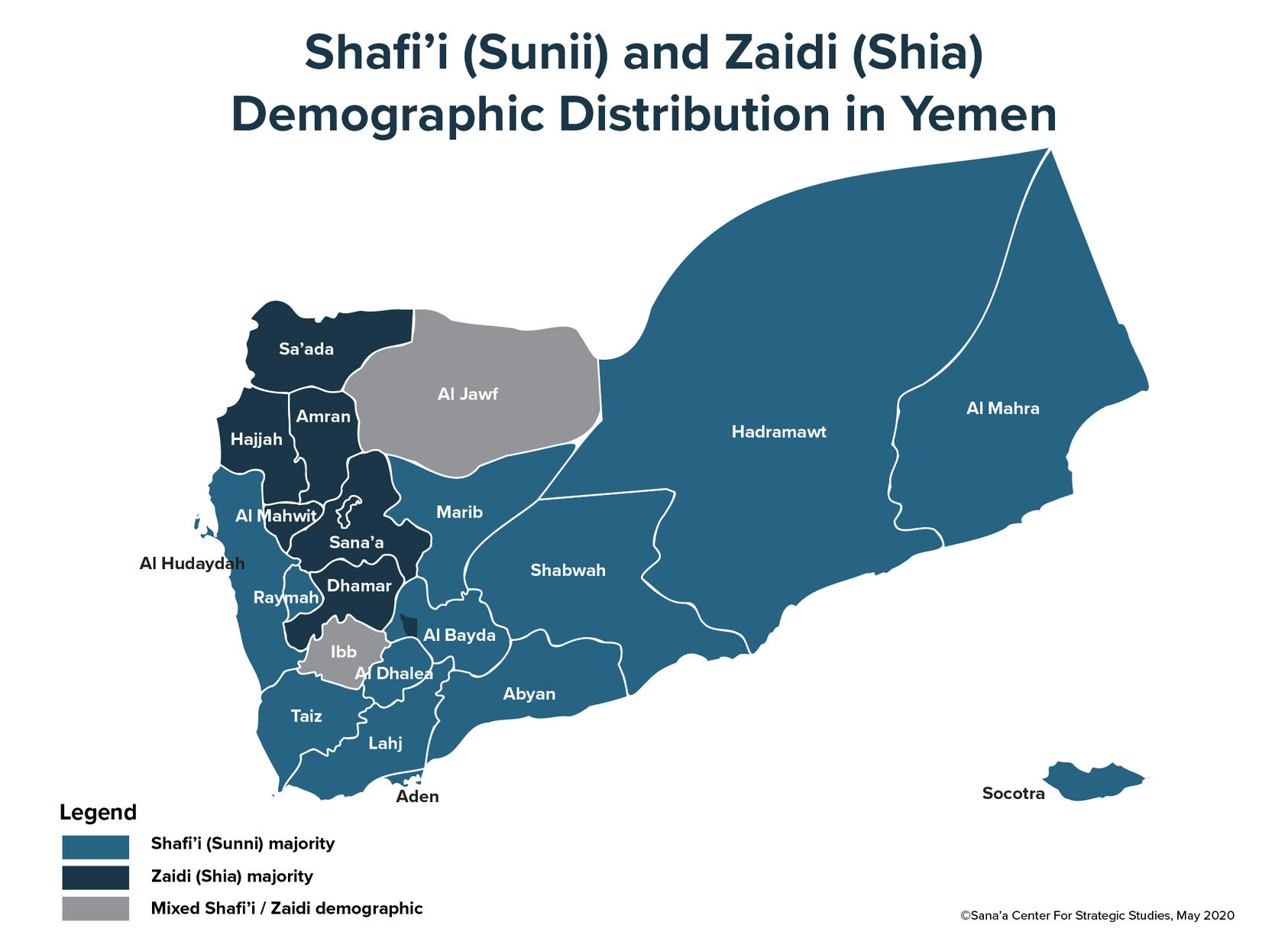

Zaydis make up the largest Shia community in Yemen. Yemen is the only state with a large Zaydi community, making Zaydism a distinctive feature of Yemeni culture. Although a relatively small group in the country, Ismailis comprise the second largest population of Shias in Yemen and in the world more broadly. Both Shia groups in Yemen are primarily found in the northern Hamdan tribe lands and in areas surrounding the capital Sana'a — a region collectively known as "Upper Yemen." Geographic, political and tribal divisions are thus closely intertwined with sectarian differences.

The political power of the dominant Zaydi Shia sect rose significantly during the early modern period. A Zaydi state was established in 1634 after the Zaydis forced the Ottomans out of Yemen. This state controlled all of Yemen for a short time until it split into separate sultanates in the southern and eastern regions in 1732. These Zaydi states persisted until a second period of Ottoman rule lasting from 1849-1918.

After the withdrawal of the Ottomans at the conclusion of World War I, the Zaydi Imamate (as the state was known) resumed its rule in northern Yemen, while the British occupied Aden and controlled the south from 1839-1967. The Zaydi Imamate continued ruling the North of Yemen until it was overthrown by the republican revolution of 1962. Even today, the influence of Zaydi Muslims continues to play a significant role in the religious landscape of Yemen.

While Zaydis are part of Shia Islam, aspects of their beliefs — particularly with respect to matters of creed and jurisprudence — are very close to Sunni Islam. There are also significant differences with other branches of Shia, perhaps the main distinguishing and controversial element of which is a political theory which requires that rulers be descendants of the Prophet — a teaching that has made the Zayidis resistant to external control and which continues to influence conflict dynamics in the contemporary period. Some Zaydis prefer to identify themselves as a separate sect altogether, separate from both Sunni and Shia denominations.

Ismailis — another Shia group — constitute another significant religious minority in Yemen and live mainly in the cities of Sana'a and Aden, as well as in the northern Haraz mountains and the Aras and Odain areas of the central Ibb governorate.

Zaydi-Ismaili Relations

Ismaili-Zaydi relations have been characterized by continuous fighting due to their political rivalry. At one point, both sects established states in northern areas of what is now Yemen. Zaydism was brought to southern Arabia by Imam Al Hadi Yahia Ibn Al Hussein in 897, who established the first Zaydi state that collapsed before he died in 911. Ismaili missionaries Ibn Hawshab and Ali ibn Al Fadhl first arrived in Yemen in 881. Later, the Ismaili Sulayhid state was founded and survived for nearly a century (1047-1138).

The rising Zaydi Imamate led to increased rivalry between the two Shia sects. Continuous fighting and fears of persecution or massacre led many Ismailis to flee to India. Due in large part to this exodus, the Ismaili sect fragmented into two groups in 1591. The Dawoodi Ismailis are mainly found in India as the descendants of those who departed Arabia in the 16th century (with smaller communities today in Yemen, Dubai and Egypt). The Musta'ilis make up the majority of Ismailis who remain in Yemen (and to some extent those in southern Saudi Arabia), and still suffer from the negative stereotypes produced against them by Zaydis during the Imamah period.

Minority Groups

While Christianity had a long history in Yemen, since the advent of Islam as the dominant religion, Christians have all but disappeared from the country. Reliable information about Christians in Yemen is therefore very sparse. Yemeni Christians live in fear of persecution or charges of apostasy and so rarely declare their religious identities publicly. The number of Christians is estimated to be between 2,000-4,000. Until recently, four churches remained in the Aden governorate from the British colonial period. However, these buildings have been destroyed, burned or damaged by extremist Sunni groups and Houthi forces during the current conflict.

The Baha’i Faith is also present in Yemen, albeit in numbers estimated to be fewer than 2,000. Some Bahai in the country are of non-Yemeni origin, such as Iranians or others who have converted to Bahaism. Bahais live quietly and mostly invisibly in different parts of Yemen, but more recently their persecution in Houthi-controlled areas has become harsher and more systematic. Bahai foundations have been shut and their properties confiscated, with many Bahai also arrested. This led some Bahais to flee Houthi-controlled areas for other regions or leave Yemen altogether. However, others have concealed their religious identities and continue living in the Houthi-controlled regions.

The Yemeni Jewish community was once one of the largest Jewish communities in the Middle East and one of the oldest Jewish communities anywhere in the world. Before Islam, Yemen was a site of competing influence between Christianity and Judaism, with the latter becoming the religion of the Yemeni state during the sixth century. Even after Islam became the majority religion in Yemen, Jewish communities continued to exist throughout the country in rural and urban areas alike.

When the state of Israel was established in 1948, Yemeni Jews emigrated in large numbers — many against their will — as part of Operation Magic Carpet, which brought 45,000 of 46,000 Jews to Israel from southern Arabia. The last official emigration of Yemeni Jews took place in 2021, when 13 people from three families were expelled from Sana'a by the Iranian-backed Houthi movement, officially known as Ansar Allah. However, some reports suggest a small number of Jewish families may still remain in Yemen.

The most prominent Shia group globally, Twelver Shia, has a small presence in Aden in the form of the Khoja, a community of South Asian heritage that settled in Aden under British rule. In 2015, a 130-year-old mosque belonging to one Khoja group who came to Yemen from India in the 19th century was destroyed by a Saudi air strike.

Religion in the Yemeni Constitution and Laws

The Yemeni constitution guarantees the freedom of belief in general, although it defines the Yemeni state as a Muslim state and conditions the Muslim religion for the president. However, the Islamic religion is not required for the members of the parliament. In addition, the permission of the president is required to build any non-Muslim worship building.

Nevertheless, apostasy is a crime based on the Yemeni apostasy law, which states that the apostate will be asked for repentance in 30 days of indulgence or sentenced to the death penalty. Therefore, this legislation prevents any Yemeni Muslim who converts to another religion from declaring his new faith.

Part II: Religion and the Yemeni War

How one understands the divisions between religious groups discussed above will directly inform perceptions of the Yemeni civil war. Often the conflict is often misportrayed as a two-sided proxy war, with the Shia Houthis supported by Iran on the one side and the internationally recognized, Sunni-dominated government supported by the Saudi-led coalition on the other side.

However, the government was never fully dominated by Sunnis (in the mid-2010s, it was actually dominated by Zaydis) and the conflict is not fundamentally driven by sectarian dynamics. The tensions in Yemen are actually geopolitical in nature, with the northern elite tending to dominate. In recent years, these power dynamics have evolved but the situation cannot be reduced to a simple formula of Shia Houthis pitted against a Sunni-dominated central government. An accurate appreciation of this complex religious-political context is critical for working toward lasting peace.

Historical Background

The republican revolution of 1962 ended the northern Zaydi Imamate that had ruled Yemen for almost three centuries (with other Zaydi imams exerting varying degrees of control for an additional seven hundred years), leading shortly thereafter to the establishment of the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR). The state of South Yemen — officially the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) — was established in 1967 after British protectorate forces withdrew in the face of armed Marxist opposition. During this period, South Yemen was the only officially communist Arab state. In turn, the Yemen Arab Republic in the north of the country was considered to be a buffer zone in preventing the spread of communism to the rest of the Arabian Peninsula. The YAR found itself on the receiving end of considerable political and material support from neighboring Saudi Arabia, a close ally of the United States during the Cold War.

To counter communist ideology, the YAR encouraged support for Islamism among Sunni groups — including the Yemeni branch of the Muslim Brotherhood movement — and the Salafis. The desire to combat communist ideology outweighed the desire to preserve traditional Zaydi doctrines and institutions that had historically dominated northern Yemen. In a further illustration of how tribal and regional identity often eclipses sectarian affiliation, this same policy was also adopted by some Zaydi presidents, including the long-serving Ali Abdullah Saleh. Consequently, Islamists — financed by both Saudi Arabia and the Yemeni government — controlled the education system in northern Yemen, resulting in the predominance of Sunni thought, even in Zaydi areas.

In 1990, following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of numerous communist governments, the two Yemeni governments unified to create the Republic of Yemen with a new system of political pluralism that elected its first parliament in 1993. In 1994, war erupted between the remnants of the socialist party in the south and the new central government based in Sana'a. The latter won the short battle, establishing uncontested control over all of Yemen. In the former PDRY, religious thought had been suppressed under the influence of communist ideology, but this completely changed after 1994 as conservative Sunni preaching expanded to the south.

At the same time, some Zaydi groups had established study centers to revive their traditional doctrines, particularly in northern areas where the community is concentrated. The Believing Youth Forum (BYF), established in the 1980s with Muhammad Azzan as one of its founders, served as the primary organizational vehicle for this trend. However, by the 1990s, two distinct camps within this neo-Zaydist movement soon emerged around the rival teachings of Azzan and Hussein al-Houthi. Of the two groups, it was al-Houthi, who was strongly influenced by the revolutionary ideology of Iran (where he had studied), who held views that were more explicitly political and even militant.

The Houthi movement adopted a more extreme interpretation of the traditional Zaydi doctrine. It championed strict religiosity and extreme, quasi-separatist ideas that reflected northern hegemonic aspirations, creating tensions with other Zaydi groups as well as the country’s Sunni majority.

Over time, the Houthis sought to distance themselves from other religious groups, both politically and in terms of religious thought. For example, the movement preached a more rigid interpretation of the Qu’ran and reintroduced the political theory of the Zaydi Imamate, which mandates a theocratic state ruled by a descendant of the Prophet. The Houthi movement's ideology can be seen as a fusion of different influences, including Zaydi principles, jihadist Salafi ideas and elements of the broader "Axis of Resistance" narrative that is associated with certain Iranian-influenced Shia groups in the region. This blend has led some observers to suggest that the Houthi movement has developed its own distinct sect, often referred to as "Houthism."

The twin extremes of Sunni Salafi preaching in the south on the one hand, and, on the other, Houthi expansion in the north gradually eroded the traditional centrism of mainstream Zaydi and Shafi’i teaching in Yemen. Both groups called for increased confrontation and heavily politicized their religious teachings. Sunni schools in Hadhramaut, long a bastion of Sufism, and a few other areas attempted to preserve traditional teachings despite the rise of Salafi and even jihadi trends in non-Houthi-controlled areas. In the north, the traditional Zaydi scholars faced censorship and restrictions in areas controlled by the Houthis.

The Advent of Civil — then International — War

By 2010, the conflict between Houthi rebels and the official government of Yemen had come to a head. The Houthis were highly organized and had expanded from their bastion in the north into the rest of the country, a development widely viewed as enabled by significant financial, military and political support from Iran.

Former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been forced from power several years earlier, also provided the Houthis with crucial military support in the form of tribal and paramilitary forces loyal to Saleh. In 2014 the Houthis took over Sana'a, storming the presidential palace and seizing government in January 2015 before attempting to take the key port city of Aden.

In response, Saudi Arabia formed a coalition of allied combatants, mostly made up of other regional Sunni powers, including Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, UAE, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Sudan which, with support from the United States, led a series of air strikes in 2015 against the Houthis. This heralded the outbreak of an all-out war in Yemen, which would last for the next eight years.

A variety of external non-state groups partook in heightening instability before and during the war, with the aim of profiting and controlling the future of Yemen. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) — a focus of global counterterrorism efforts ever since the U.S.S. Cole bombing in 2000 and the subsequent activities of Anwar Al-Awlaki — was active since the beginning of the war, controlling the city of al-Muklla, the capital of the biggest Yemeni governorate, Hadramout.

By 2016, they were forced to leave the city and their political relevance became marginal. The Yemeni faction of the so-called “Islamic State of Iraq and Syria” (ISIS-Yemen) has played a very minor role in Yemen’s ongoing conflict — mainly through assassination and guerilla-style attacks in the area of Baydha — but its presence has also been weakened. Since the fall of Sana’a to the Houthis in 2014, the conflict between all of these groups and factions has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and contributed to one of the worst humanitarian crises in the modern world.

The country remains highly fractured. The heavily populated northwest region of Yemen is controlled by the Houthis, in which significant numbers of Zaydis and Sunnis reside. The highly factionalized government of Yemen controls the central and eastern regions of the country. The south is splintered into various governorates, five of which — in addition to the coast of Hadhramaut — are controlled by a secessionist state known as the South Transitional Council (STC) backed primarily by the UAE. However, the two largest jurisdictions (inland Hadhramaut and al-Mahra) remain outside of the STC’s control. While large-scale fighting has largely ended since a cease-fire was agreed upon in 2022, progress toward a meaningful and lasting end to the conflict has been slow and difficult.

Prospects for Peacebuilding: Religious Women and Tribal Leaders

Yemeni women have struggled for political inclusion and to achieve positions in government. In 2011, with social and political tensions already rising, Yemeni women were visibly active in leading peace demonstrations, such as the Nobel Prize winners Tawakkol Karman (at the time a member of the Islamist Islah party) and Bushra Al Maqtari.

Yemeni women succeeded in gaining a 30 percent share of the seats in the National Dialogue Conference that occurred during the transitional period of 2012-2014 — a particularly noteworthy achievement considering Yemen’s low literacy rate and ranking at the very bottom of the U.N.’s 2019 Gender Inequality Index.

The war and rising influence of various Islamic groups have dismantled these gains and achievements. Restrictions on women were imposed by the Houthi authorities, including a requirement for male guardianship in order to travel. The requirement for a male guardian, or mahram, to be present at legal or other official proceedings involving female family members has become common. Women also experience acute hardship in areas controlled by the internationally recognized government due to exposure to harassment from various armed groups. This deterioration of women’s rights was encapsulated by the internationally recognized government forming a cabinet in 2022 without women's representation for the first time in two decades. However, this adversity faced by women remains less systematic compared to Houthi-controlled areas.

Yemeni women, often invoking religious inspiration and justification for their activism, continue to mobilize for political representation in peace negotiations. Leaders such as Maien Al Obiedi, Olfot al-Dubai, Roma al-Damasi, Muna Luqman, and Afraa al-Hariri succeeded in conducting many agreements between social and military factions to decrease violence or provide oversight vis-à-vis the security forces.

Women remain active in advocacy efforts, as demonstrated by the Feminist Summit and organizations like the Peace Track Initiative and the Yemeni Women Union, which provide legal assistance to Yemeni women. The Abductees Mother's Association speaks out against forcible disappearances and illegal arrests, both of which are common practices among all armed groups in Yemen. This organization documents these violations of international law and provides support to families advocating for the release of abducted loved ones.

Tribal structures and laws have also played a vital role in conflict mediation processes. Such interventions have deescalated violence, reopened roads and led to the exchange of thousands of war prisoners. Some tribal figures have played particularly notable roles, such as Hadi Jumaan, who succeeded in brokering negotiations that allowed the bodies of war, which numbered in the thousands, to be exchanged between conflicting parties.

Conclusion

Religion in Yemen is a significant social and cultural force that influences every aspect of society. The ongoing conflict in Yemen is at once a local power struggle as well as a proxy conflict for larger geopolitical and regional-sectarian rivalries.

At the same time, to ascribe Yemen’s conflict to religious differences would detract from other factors — such as geographic divisions and historical grievances regarding political power and territory — that have been more proximate drivers of violence. Nonetheless, religious groups and voices will likely play a critical part in Yemen’s reconciliation process in the years ahead. Policymakers and peacebuilding practitioners engaging in this complex conflict must seek to understand both the religious currents which have stoked violence in Yemen, as well as tap religious actors and resources which could help to alleviate tensions.

This primer was drafted by Sana'a Center for Strategic Studies Senior Researcher Maysaa Shuja Al-Deen with input from Nadwa Al-Dawsari as well as USIP Religion & Inclusive Societies Researcher Mona Hein and Senior Advisor Peter Mandaville.