What Does the Singapore Summit Mean for South Korea, China and Japan?

USIP experts examine how the historic meeting between President Trump and Kim Jong Un will impact the Asian powers.

The June 12 summit in Singapore between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un was a watershed moment in relations between Washington and Pyongyang. But, the more immediate and profound impact will be felt in East Asia, where North Korea’s nuclear program has threatened regional stability and security. While South Korea, China and Japan have different—sometimes starkly so—interests and positions vis-à-vis North Korea, all three of the Asian powers will be important players in efforts to implement the pledges made in Singapore. USIP’s Ambassador Joseph Yun, Jennifer Staats and Frank Aum discuss the implications for Seoul, Beijing and Tokyo.

Cautious Optimism in South Korea

Ambassador Joseph Yun: Outside the directly involved leaders, Republic of Korea (ROK) President Moon had the most at stake in the U.S.-North Korea summit. After essentially brokering the summit—and getting turned down by President Trump for a three-way meeting in Singapore—Moon apparently spent a sleepless night in the Blue House waiting for the meeting to take place. Most South Koreans were similarly worried—and excited—about the historic meeting between the leaders of their archenemy and their protector ally. That the meeting was held at all, especially that the two leaders were warm and friendly to each other, was welcomed by even the most conservative of South Koreans.

For President Moon, who had promised the nation that there would never be another war on the Korean Peninsula, the summit leant proof that a U.S. military option was now virtually off the table. Moon was the first leader to congratulate President Trump and Kim Jong Un on the "successful outcome" of the summit, pledging that the ROK government (ROKG) would do all it could to implement the Singapore Joint Agreement. However, there were some surprises too for South Koreans and President Moon.

Most significantly, President Trump announced in the post-summit press conference that he had agreed to stop all "war games," or joint U.S.-ROK military exercises, which he characterized as provocative and expensive. Although the ROKG made it clear that it was not consulted, Seoul quickly supported the move, as stopping the joint exercises would contribute to the successful negotiations between the U.S. and North Korea. However, there remains deep concerns among South Koreans about the Trump administration's overall commitment to the alliance, especially as President Trump also made it clear that he favored an eventual withdrawal of U.S. troops, provided the security conditions on the Peninsula warranted such a move.

South Koreans had also expected to see a more concrete commitment to denuclearization. For President Moon, who had given his assurances that Kim Jong Un had agreed to completely denuclearize, the Singapore Joint Agreement was a clear disappointment. Without rapid denuclearization, his plan to quickly provide economic assistance and fund investments into North Korea will be delayed, perhaps even beyond his remaining time in the Blue House.

Still, most South Koreans remain optimistic that the relations between Washington and Pyongyang have turned around and a return to "fire and fury" is not in the cards for the foreseeable future. However, in the coming months, they will want to see a stronger commitment to denuclearization by North Korea as well as clear assurances from Washington that it remains committed to the U.S.-ROK mutual defense treaty.

China Remains Central to Diplomacy on the Korean Peninsula

Jennifer Staats: China is pleased with the results of the summit itself, and events of the last week have further strengthened China's hand.

Beijing's objectives vis-à-vis North Korea have long included avoiding military conflict, sustaining a diplomatic process toward denuclearization of the Peninsula and a future peace agreement, and setting the stage for eventual reform and opening up of North Korea—and all of these goals were advanced in last week's meeting between President Trump and Chairman Kim. After the formal talks ended, China's position continued to improve.

China was particularly pleased with President Trump's press conference following the summit, where he unexpectedly pledged to halt "provocative" "war games" with South Korea, praised China's contributions in the lead-up to the meeting, called for China to have a role in future peace treaty negotiations, and said he hoped to remove U.S. troops from the Korean peninsula "at some point" in the future.

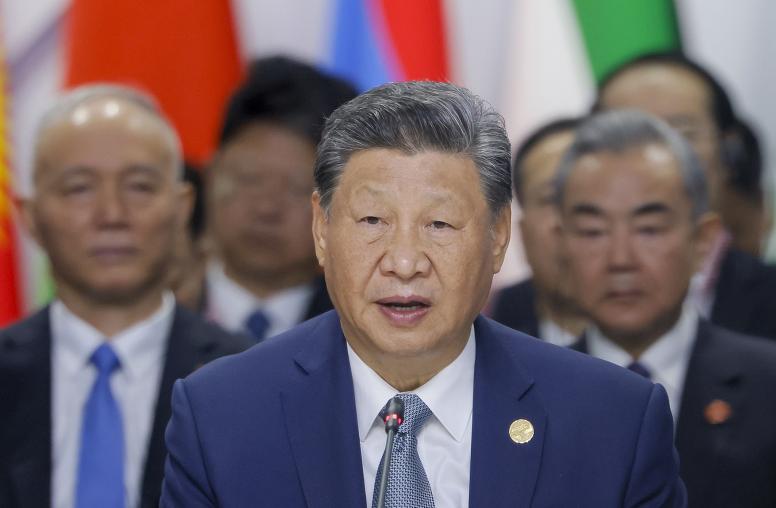

Perhaps most importantly, the bilateral relationship between China and North Korea is now back on solid ground. Kim took office at the end of 2011, but did not meet with China's President Xi until March 2018, following President Trump's agreement to meet with the North Korean leader. Kim traveled to China twice in the months before the summit, and returned to Beijing this week to meet again with Xi.

Washington needs China to use its economic and political leverage to pressure North Korea toward denuclearization. With the announcement of new U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods and a potential trade war looming, however, China may be less likely to cooperate.

Many in China are skeptical that North Korea will ever give up its nuclear weapons, but they want the diplomatic process to continue—and are pleased that China once again has a role at the center of it.

Japan: On the Outside Looking in

Frank Aum: So far, Japan has been the one regional player on the outside looking in, not having been able to secure a senior-level meeting with North Korea. Instead, it has had to rely on Washington and Seoul to push for its interests.

Japan shares the U.S. and South Korean interest in achieving sustainable peace and stability in the Northeast Asian region by securing North Korea's complete denuclearization. Likewise, Tokyo agrees with Washington and Seoul that sanctions on North Korea should not be eased until it takes concrete steps toward denuclearization. However, Japan is also concerned about the fate of its citizens that were abducted by North Korea in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as well as the full range of North Korea’s ballistic missiles, which can reach or overfly its territory.

With North Korea having committed to complete denuclearization at the Singapore Summit and the abductees issue having been raised by President Trump, enough of Japan's concerns appear to have been addressed to keep it on board with the overall rapprochement process.

Nevertheless, President Trump's cancellation of major U.S.-ROK joint military exercises—calling them provocative and expensive—likely surprised Tokyo and raised concerns about U.S. reliability. Conceding a major deterrence mechanism without consulting with allies and without an equivalent concession from North Korea, especially within the context of President Trump's perceived retrenchment from Asia, undermines Japan's confidence in the U.S. security commitment.

Going forward, Japan will continue to stay in lockstep with the United States and South Korea, reiterating a strong U.S.-Japan security commitment and the need to maintain close consultations between allies. But it is also likely that Japan will try to seek its own summit meeting with North Korea so that it can regain its own agency and not be responsible for signing a check at the end that was negotiated by an erratic U.S. ally.