As China Projects Power in the Indo-Pacific, How Should the U.S. Respond?

Representatives Case and Rutherford call on Congress to continue to shed light on Beijing’s coercive tactics.

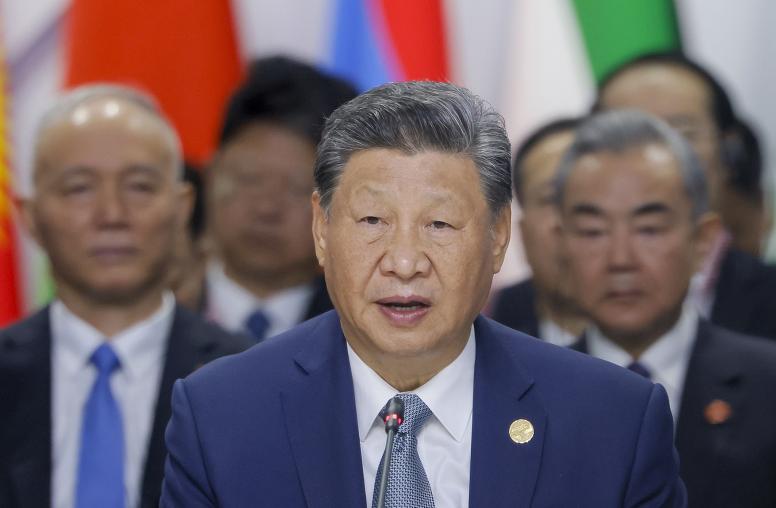

There is a growing bipartisan consensus in Washington that China’s ascendance is a major strategic concern for U.S. and international security and stability. This is reflected in the 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy, which recalibrates U.S. foreign policy to address the challenges posed to American power and interests from escalating geopolitical competition with China and Russia. After a recent trip to the Indo-Pacific region, Rep. Ed Case (D-HI) and Rep. John Rutherford (R-FL) said they came away alarmed at how China is tightening its grip on U.S. allies across the region. What can the U.S. do to address China’s power projection and coercion in the Indo-Pacific and beyond?

That is a question that Congress is increasingly focused on, said Rutherford last week at the U.S. Institute of Peace’s Bipartisan Congressional Dialogue. And for good reason: “The [U.S-China] relationship will define our world for future generations,” said Case.

China’s Power Projection

It’s been six years since China introduced its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive, trillion-dollar infrastructure and investment project that spans the globe. Rutherford said he worried that the BRI “is planting a future where Chinese, not U.S. leadership, is assumed.” “China isn’t just building ports or airfields without some sort of aim or strategic incentive,” added Case.

China is “leveraging military modernization, influence operations and predatory economics to coerce other nations” to reorder the region to its advantage, said a Pentagon strategy report on the Indo-Pacific released in June.

One of the most illustrative examples of China’s coercive tactics is in Sri Lanka. Two years ago, Sri Lanka gave China a 99-year lease and controlling stake in its Hambantota port as a way to meet Colombo’s unsustainable debt loads, even though local communities protested over fears of a loss of sovereignty. Beijing turned its ally’s struggles into its strategic advantage. “What happened in Sri Lanka should never happen again,” said Rutherford.

A recent USIP Special Report found that smaller South Asian nations are “increasingly aware of the potentially negative impacts and unintended consequences of Chinese financing of development projects.” And while there are certainly drawbacks, the report did find that these countries have benefitted from the increased connectivity that has come with the BRI.

For many countries unable to attain financing for large-scale infrastructure projects, the BRI is the only game in town—but one that can come with a steep price. “Many BRI partners are now worried about the dangers of debt distress, loss of sovereignty, increased corruption, environmental degradation, lack of transparency, and unfair labor practices that often accompany these projects,” wrote Jennifer Staats, the Institute’s director for East and Southeast Asia Programs, in a USIP commentary. Despite the Chinese government’s lofty rhetoric, “the initial euphoria has largely turned to fatigue,” she wrote.

While the congressmen’s remarks focused on China’s efforts in the Indo-Pacific, both acknowledged that Beijing is seeking to project power and influence from Latin America to Africa to Central Asia with similarly coercive tactics.

A ‘China-Based Order’

The U.S. has sought to bring China into the fold of the rules-based international order—just look at China’s 2001 admission to the World Trade Organization. But, Beijing, said Case, is influencing the rules-based order in an effort to foster a “China-based rules order.” “We hoped that extending the rules-based order to China would mean it became a part of it,” said Case, but “China has picked and chosen when to follow this order; the South China sea is the best example.”

China isn’t hemmed in by democratic norms and values, said Case. Beijing has “the kind of political system that allows them to work for the long game,” Rutherford concurred.

In the Indo-Pacific, many countries are trying to maintain a delicate balance, where China is their most important economic partner, but the U.S. is the most important strategic partner. China wants to reorient the regional order so that it’s both the most important economic and military partner. Rutherford said he was “amazed to see the imbalance of military power in the Indo-Pacific.”

Ultimately, the U.S can accommodate Chinese efforts to pursue its goals within the rules-based order, but, said Case, “always from a position of strength.”

The U.S. Needs a Comprehensive Approach

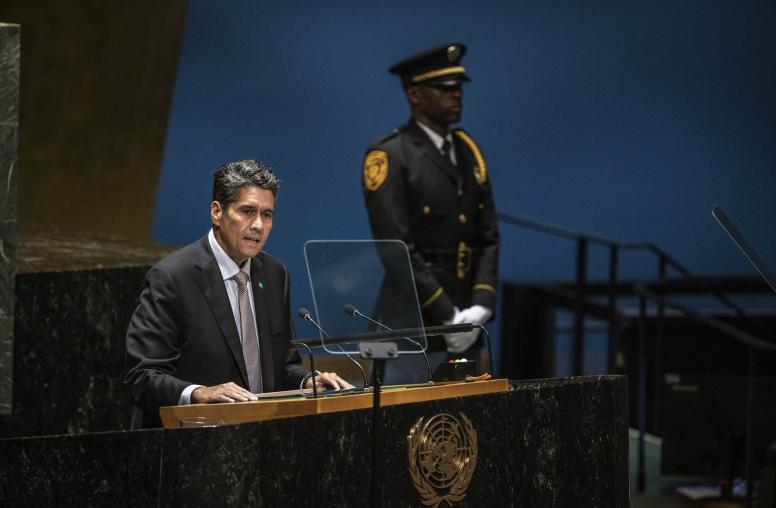

The U.S.-China relationship is “deep and complex,” said George Moose, the vice chair of USIP’s Board of Directors, who moderated the discussion. “How do we sort through this complicated agenda?” he asked. In response, Rutherford said, “We need to start bringing light to the economic coercion that China is using throughout the world … Most folks have no idea how bad it is.”

He argued that the U.S. should pursue bilateral trade agreements with American partners and allies in the region as a way to counter China’s economic influence. After all, “America first, doesn’t need to mean America alone,” Rutherford said. Case also discussed the importance of partnerships in the region, pointing to countries like Japan, Australia, and Singapore and the constructive engagement the U.S. has had with these allies. “We need to partner with the rest of the world to provide an alternative.”

Unfortunately, said Case, “We have been inconsistent in our focus on those alliances. These alliances need strengthening.” Rutherford agreed: “[The U.S. is] still the partner of choice in the region, but they [Indo-Pacific countries] are beginning to question our resolve and whether [the U.S.] will truly be there for them.”

While continued investment in a strong military is important, projecting “other forms of influence in the region needs to be there,” said Case. “There needs to a cohesive, overall approach” that promotes U.S. interests and values in free trade, development, democracy, and human rights.

Looking at U.S. soft power, Case said, “Our cultural response is important,” adding, “democracy is a better way of life.” Indeed, Rutherford argued that the U.S. needs to “be aggressive in efforts to win hearts and minds” in the region and “show our allies that the U.S. is ready to take on these challenges.”