What Does Qin Gang’s Removal Mean for China’s Foreign Policy?

The mysterious disappearance of Beijing’s foreign minister demonstrates how opaque China’s political system is — and how much Xi Jinping dominates it.

Speculation has run rampant the last month over the whereabouts of China’s foreign minister, Qin Gang. Rumors ranged from the salacious (he had an affair) to the mundane, while the official line states that he is dealing with health problems. On Tuesday, China officially replaced Qin with his predecessor, Wang Yi, who leads the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) foreign policy apparatus. Qin’s removal from office, and the erasure of references to him and his activities on official Chinese government websites, have only furthered interest into what happened. Beyond the political intrigue, the more substantive question is what this means for China’s diplomacy.

USIP’s Rosie Levine, Andrew Scobell and Adam Gallagher discuss the implications for China’s foreign policy, what this incident reveals about China’s political system and lessons for U.S. policymakers.

What are the implications for China’s foreign policy?

Levine: China has its work cut out for itself to manage the bad the optics of Qin Gang’s sudden removal. Chinese foreign policy rhetoric has spent years trying to position itself as a responsible and stabilizing fixture on the world stage. In much of China’s foreign policy outreach, it fashions itself as a trusted partner who can be relied upon for its predictability and long-time horizons — in contrast to the United States, which is cast as unstable and easily swayed by domestic politics.

Qin’s mysterious disappearance, followed by his removal and a complete scrub of all mentions of his activities on the Foreign Ministry website, points to a political purge. This episode is a stark reminder that China’s opaque political system remains determined by the whims of an apparatus we largely do not understand. Countries seeking to engage with China’s foreign policy system will look to this as a reminder of the ways that policymaking in China can be erratic and ultimately driven by domestic politics, despite the rhetoric to the contrary.

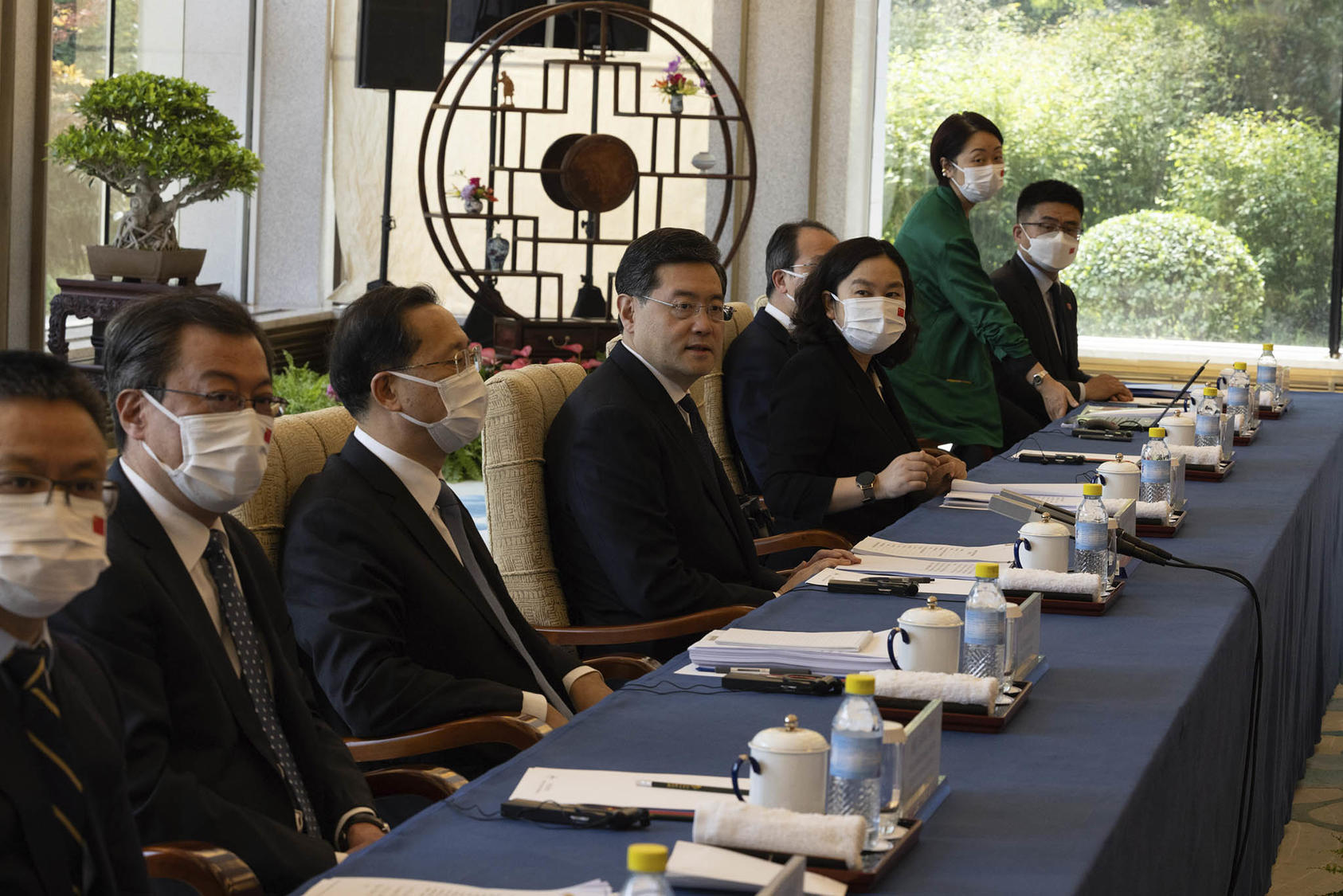

The next important implication for foreign policy stems from the differences in how Qin and Wang conduct diplomacy. Wang’s return as foreign minister may signal a further shift away from China’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy. Before serving as one of China’s youngest foreign ministers, Qin was selected for a number of high visibility positions within the Chinese foreign ministry including Chinese ambassador to the United States, Foreign Ministry spokesman and chief protocol officer (directly involved with Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s engagements and meetings).

As spokesman he is seen as a pioneer of China’s assertive “wolf warrior” style of diplomacy, which aggressively defends China’s foreign policy agenda on the global stage. Wang, by contrast, is seen as a more traditional bureaucrat who held the post of foreign minister for almost a decade, before being elevated to the role of director of the Communist Party’s Foreign Affairs Commission Office last year. Wang has built strong relationships with key foreign policy counterparts around the globe and is seen as a steadying force Chinese foreign policy.

Qin’s quick rise through the ranks was widely interpreted as a reward, granted directly by Xi, for his assertive style of diplomacy. His unceremonious removal may indicate that his style of diplomacy is losing favor. In recent years, other “wolf warriors” have been reassigned to lower-visibility roles. Wang’s return as foreign minister could signal a further shift in Chinese foreign policy tone away from “wolf warrior” rhetoric and assertive foreign policy claims, in favor of more traditional Chinese foreign policy approaches. Some analysts have also called Wang a “wolf warrior,” but over the years he has demonstrated more adaptive approaches to foreign policy often presenting different modes depending on the audiences and policy objectives. This has ranged from aggressive language, to constructive approaches and some awkward misses.

Ultimately, we should not expect a dramatic shift in China’s foreign policy, but stylistic and personality changes could make a difference — particularly in U.S.-China relations where substantive engagements have been limited to high-level meetings, which rely upon the personalities and approaches of those top leaders themselves.

What does this demonstrate about China’s political system?

Scobell: The month-long disappearance of Qin Gang and abrupt removal from his post as foreign minister underscores two core features of politics in contemporary China.

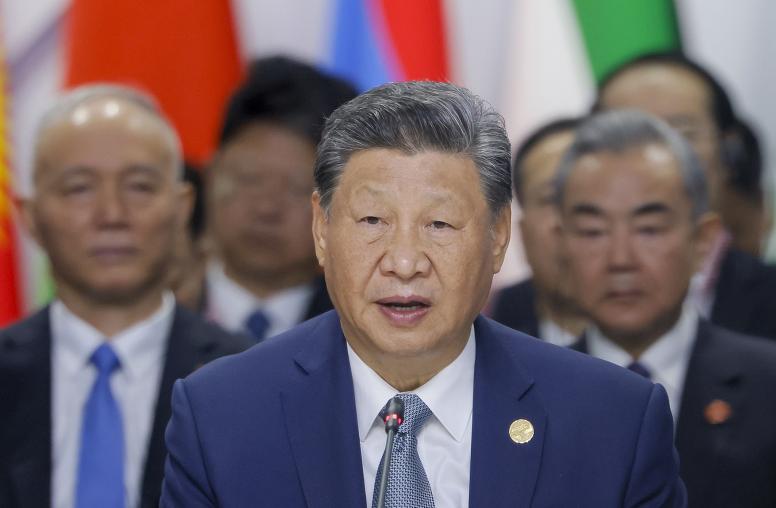

First, China’s entire political system is opaque and orbits around one man: Xi Jinping. Since taking office a decade ago, Xi has consolidated his personal hold on power tighter than any top leader since Mao Zedong (1949-1976). Xi now exercises centralized control over all major bureaucratic systems, to include the Communist Party, the People’s Liberation Army, and state — People’s Republic of China — ministries, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Xi also spearheads all key policy initiatives. No dimension of the political system is more important and less transparent than personnel management: the selection, promotion and dismissal of leaders in each of these bureaucracies. This is especially true when it comes to the matter of China’s most consequential and enduring foreign policy challenge: the United States.

Second, China’s strongman selects, promotes and removes officials primarily on the basis of loyalty, specifically according to an individual’s perceived personal fealty to Xi. While competence is not unimportant, loyalty is paramount. Loyalty is the key criterion for personnel selection because leaders like Xi are never sure about who they can trust (China is a low trust society and its communist rulers are ultra paranoid about conspiracies and betrayal).

One personnel management strategy adopted by both Xi and his predecessors, notably Mao, is to promote people who owe their advancement entirely to the top leader — individuals who have weak or non-existent factional networks. Qin appears to be such an individual. A dictator can literally pluck a junior official out of obscurity and promote this person knowing that their loyalty is almost guaranteed because the individual knows full well their selection was made solely because they were anointed by the man at the top. Another key factor in selection criteria is an individual’s perceived weaknesses or flaws, which makes that person even more beholden to the top leader. This blemish could be an embarrassing episode in their past or current picadillo, such as corruption or sexual promiscuity, that if made public would mean the end of their career. Qin is rumored to have had an extramarital affair while he was stationed in Washington as China’s ambassador to the United States.

What does this mean for the efforts to improve U.S.-China relations? Are there lessons for U.S. policymakers?

Gallagher: Qin Gang’s mysterious disappearance and subsequent replacement as China’s foreign minister coincides with a much-needed thaw in U.S.-China relations. Secretaries Blinken and Yellen and Special Envoy John Kerry have all been in Beijing in recent weeks and Blinken met with Wang Yi at last week’s ASEAN summit in Indonesia. While speculation is rampant about the reason for Qin’s removal, one reason may be his poor handling of tense relations with Washington — particularly Qin’s failure to mount an effective response to President Biden calling Xi a “dictator” after Blinken’s visit to Beijing — at an important moment in the bilateral relationship.

Wang’s reappointment does suggest that Xi wants to continue relatively positive trends in engagement and build a more stable relationship with Washington ahead of a potential tête-à-tête with Biden at the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation leaders’ meeting in San Francisco this November. Although Wang has often harangued U.S. officials and harshly criticized U.S. policy, he is a known commodity in Washington. Now he sits at the head of both the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the Communist Party’s Foreign Affairs Commission. He’s also a member of the CCP’s ruling Politburo and one of Xi’s most trusted aides. So, U.S. diplomats can be confident that Wang’s public and private pronouncements align with the upper echelons of the Chinese government and Communist Party.

This whole affair reinforces that Xi is the ultimate arbiter of Beijing’s policy and posture toward Washington — and everything else for that matter. Xi appointed Qin as foreign minister over other more seasoned Chinese officials and he very clearly made the call to remove Qin. Thus, it is unlikely that Wang’s reappointment will lead to any real change in China’s U.S. policy unless it is at Xi’s behest. Personnel shuffling does not address the structural challenges in U.S.-China relations.

Whatever the reason for Qin’s removal, it demonstrates a troubling lack of transparency that should stay in the back of minds of U.S. policymakers and diplomats in their dealing with Beijing. Diplomacy is often a painstaking and iterative trust-building process. If China cannot be forthright about the status of its leading officials, why should the United States or any other government trust China in sensitive diplomatic discussions? This episode is not only embarrassing for Xi but could lead to understandable reticence among U.S. policymakers and diplomats in their engagement with Chinese officials.